I’m a clinical psychologist by training. When I stumbled into the marketing profession about 20 years ago, ‘psychologist’ was something you better kept for yourself. Back then, I’d much better confessed at a party that I rented out some windows in the red light district than to admit I studied psychology. At that time, psychology was considered to be ‘the sinkhole of the university’. But things have changed…

Applied psychology: Things have changed

This perception profoundly changed in the last 10-15 years. The first trigger event was the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for the work of Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. This was the first time that the field of economics fully acknowledged the importance of psychology to understand better how humans make decisions in markets.

/br>

In the slipstream of Kahneman and Tversky’s Prize and their best-seller “Thinking Fast and Slow“, behavioural psychology got reframed brilliantly into Behavioural Economics. A friend of mine, a professor at a Dutch Management School, told me that ever since he changed “psychology” into “behavioural economics” in his research grant proposals, he won every grant for which he applied.

/br>

The insaturable appetite for psychology caused an explosion of books that promised to provide deep insight into turning deep human understanding into persuasive products and services.

/br>

Tech companies perfectly understand that behavioural science is the ultimate competitive edge.

Applied psychology: critical sectors are not using it

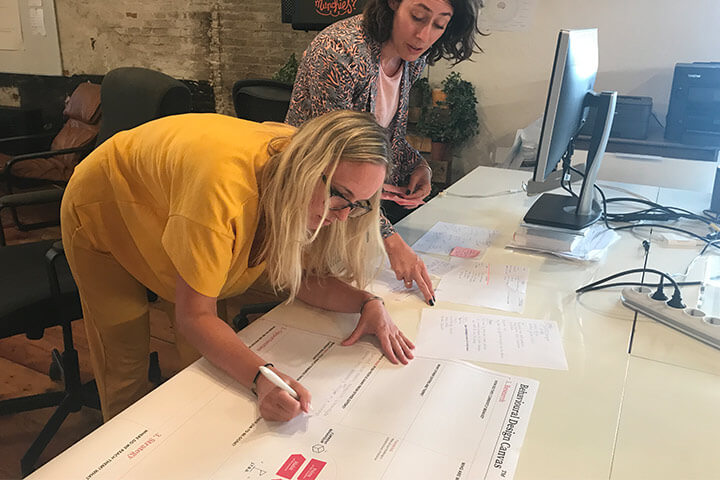

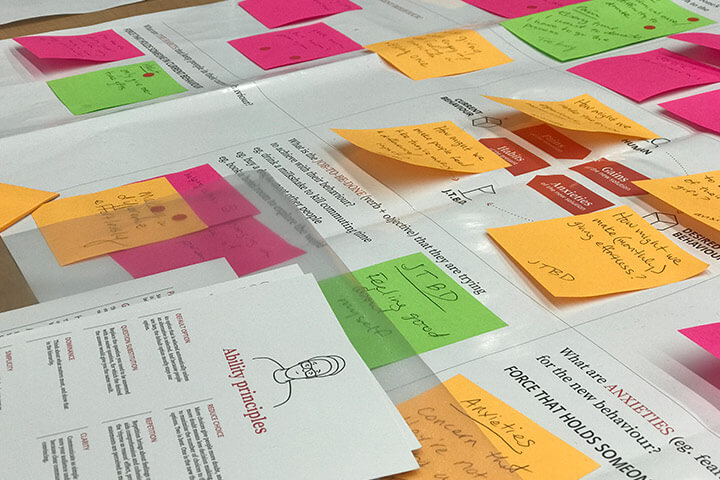

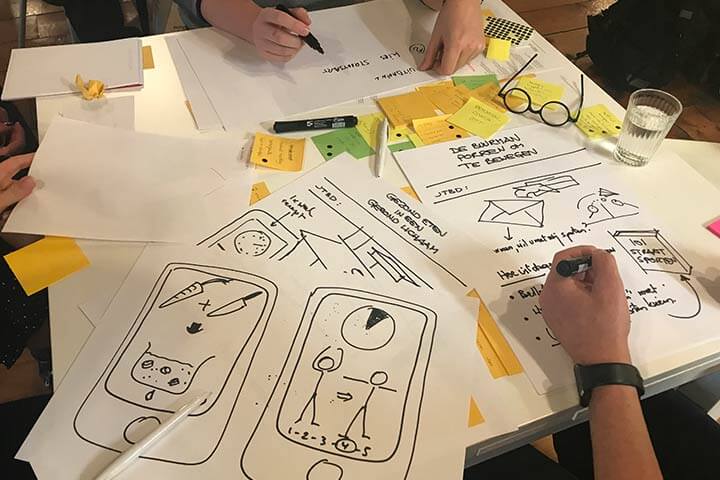

Want to learn how to design behaviour?

Join our two-day Fundamentals Course and master a hands-on method to use behavioural science to develop ideas that change minds and shape behaviour.

Summary: Applied psychology

Featured cover image by Markus Winkler on Unsplash.

How do you do. Our name is SUE.

Do you want to learn more?

Suppose you want to learn more about how influence works. In that case, you might want to consider joining our Behavioural Design Academy, our officially accredited educational institution that already trained 2500+ people from 45+ countries in applied Behavioural Design. Or book an in-company training or one-day workshop for your team. In our top-notch training, we teach the Behavioural Design Method© and the Influence Framework©. Two powerful tools to make behavioural change happen in practice.

You can also hire SUE to help you to bring an innovative perspective on your product, service, policy or marketing. In a Behavioural Design Sprint, we help you shape choice and desired behaviours using a mix of behavioural psychology and creativity.

You can download the Behavioural Design Fundamentals Course brochure, contact us here or subscribe to our Behavioural Design Digest. This is our weekly newsletter in which we deconstruct how influence works in work, life and society.

Or maybe, you’re just curious about SUE | Behavioural Design. Here’s where you can read our backstory.