Can we design a choice? In most societies, if there is one value we hold dear, it is our freedom of choice. Having autonomy is a concept that directly speaks to our core as human being. Suppliers of goods and services understand this and have submerged us in an economy of choice that can match everyone’s individual needs. It fits our need for autonomy like a glove. It allows us to be in the driver seat of our own lives. But is it? Is it true? Does abundance help us make better decisions? Does more choice equal more satisfaction? The answer is no. So, the question is: How we can master the subtle art of choosing to shape better decisions and positive behaviours?

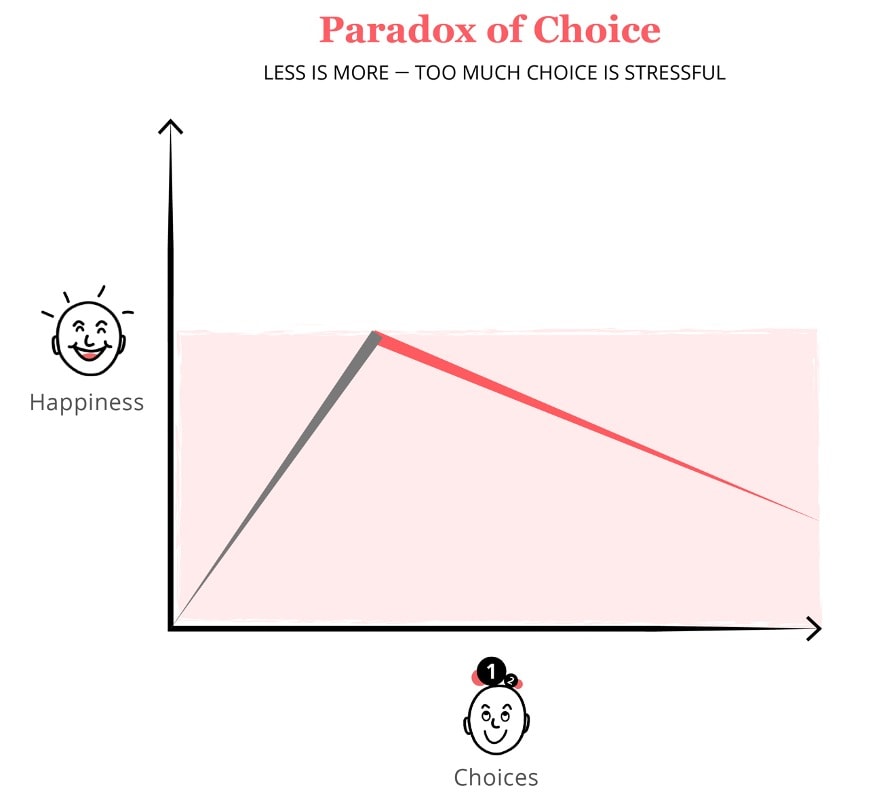

How to design a choice: The paradox of choice

Something interesting is going on which choice. It is a paradox, a concept cornered by Barry Schwartz. He describes the paradox of choice as follows:

So, what does this implicate? Is less indeed more? Well, yes and no. In most cases, too many options to choose from isn’t in our best interest. This has to do with our bounded rationality. We, as human beings, cannot make every decision in our daily lives wholly rational or, better put, with focused attention. There are too many decisions for us to deal with to do so.

Just think about your morning. From the moment you heard your alarm go off, you had to decide to turn it off or snooze. You had to decide to stretch or do another roll-over on your side right into that comfy spot that has the perfect temperature; You had to decide to get up or sleep in for just a little bit longer. You had to decide to get dressed right away or get your first coffee in PJ’s first. You had to decide to have coffee indeed, or did you decide to have something else? Or did you decide to go pee first? I have not even begun to talk about the decision to check your phone, turn on the radio, heating or toaster yet. Or the decision to combine all of these with checking your to-dos of the day. And your day has only just started.

These examples all may seem trivial, but they’re not. It is estimated that your brain has to compute about 35.000 decisions a day, from minor ones to bigger ones. Your brain cannot process all of them consciously or with extensive thought; It would simply crash. Therefore, a lot of our decisions are made automatically and unconscious. As Nobel laureates Kahneman and Tversky have discovered, we have two operating systems in our brain: A deliberate and an automatic one. And the automatic one has the upper hand, which is a good thing. It simply shows our brain is wired to help us navigate as with as little effort as possible through life.

How to design a choice: The phenomenon of choice overload

Now back to too many options to choose from. Why does it work against us?

First of all, having too many options causes apathy simply as it requires too much cognitive activity. This can lead to decision fatigue or even not making any decision at all. This phenomenon is called choice paralysis (also referred to as choice deferral).

There is a cognitive bias related to this phenomenon called regret aversion. When people anticipate regret from a choice, they tend to not act at all. This can have severe consequences. A meta-analysis has shown that people’s behaviour to accept medical treatments is influenced more to avoid regretting making the wrong choice than it is influenced by other kinds of anticipated negative emotions. Therefore, when designing a choice, you have to be aware that the number of options you present to someone also enhances the probability of choice regret. Which in return enhances inertia. In the mentioned example, this has shown to seriously impact behaviour concerning health.

There is a cognitive bias related to this phenomenon called regret aversion. When people anticipate regret from a choice, they tend to not act at all. This can have severe consequences. A meta-analysis has shown that people’s behaviour to accept medical treatments is influenced more to avoid regretting making the wrong choice than it is influenced by other kinds of anticipated negative emotions. Therefore, when designing a choice, you have to be aware that the number of options you present to someone also enhances the probability of choice regret. Which in return enhances inertia. In the mentioned example, this has shown to seriously impact behaviour concerning health.

Secondly, when we have more options to choose from, we tend to make worse decisions as we tend to rely even more on our system 1 cues, which can be biased. Examples are our tendency to stick to defaults, recommendations, or reliance on peer choices. Have you ever said in a restaurant: I am having what he/she is having’? Well, probably this was caused by option overload on the menu. Research showed what happens if there are either six or thirty food options on a menu. In the first case, people tend to choose for themselves. In the second case, they choose what their partner chooses.

Thirdly, we tend to make more conservative choices to minimise the potential for regret.

And finally, the more options to choose from we have, the less satisfied we are with the choice we did make. The more options, the more we feel we ‘missed out on.’ In his book, Schwartz described two experiments. One in which people had to choose between 20 varieties of jams and another could choose between six models of jeans. The experiment showed that the more choices people had, the less satisfied they were with their final choice. This matches Sheena Iyengar’s research, professor at the Columbia Business School and author of ‘The Art of Choosing’, which taught us that:

‘The existence of multiple alternatives makes it easy for us to imagine alternatives that don’t exist. And to the extent that we engage our imaginations in this way, we will be even less satisfied with the alternative we end up choosing. So, once again, a greater variety of choices actually makes us feel worse.‘

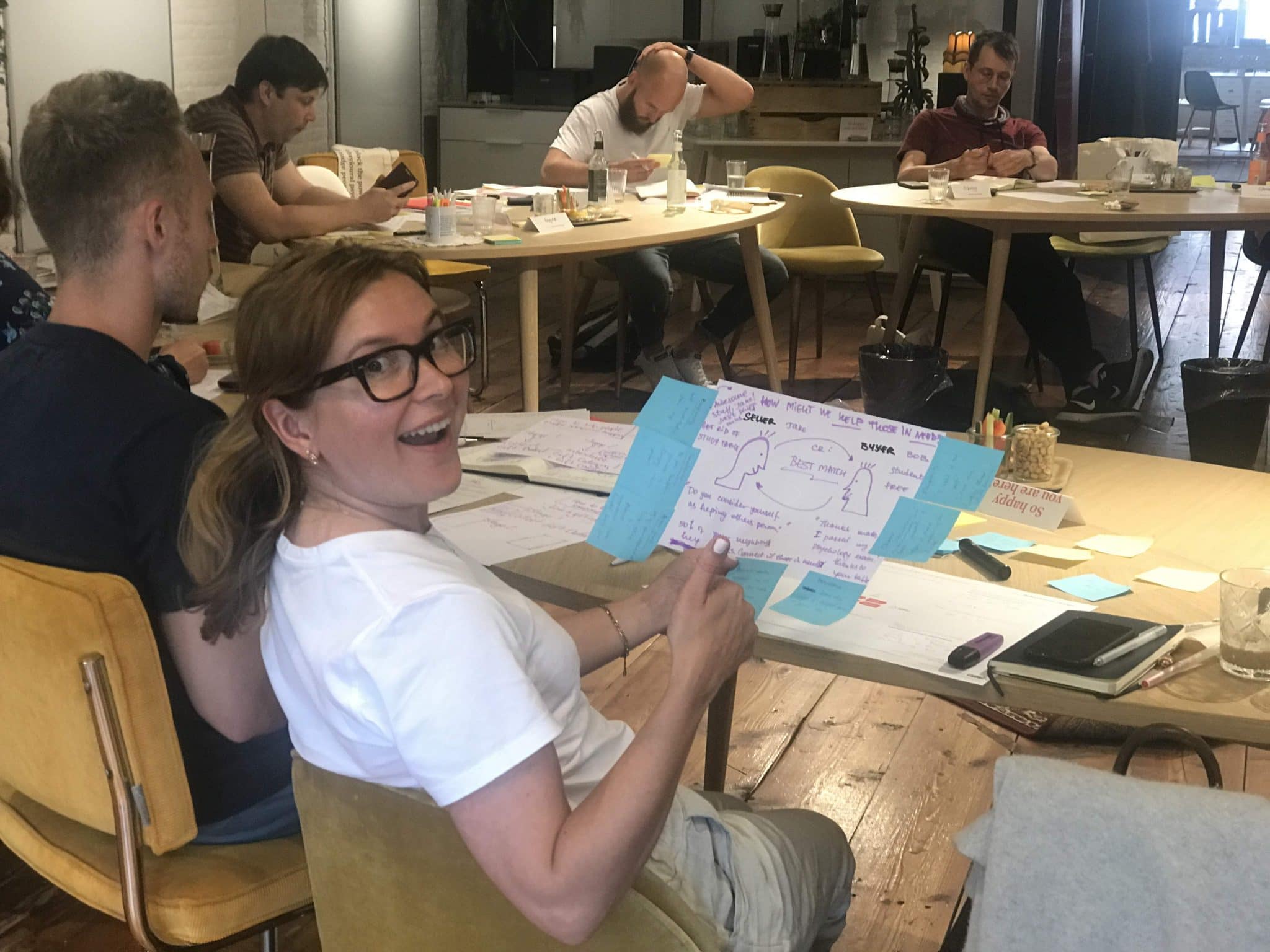

Want to learn how to apply behavioural science in practice?

Then the Fundamentals Course is perfect for you! You'll catch up on the latest behavioural science insights and will be handed tools and templates to translate these to your daily work right away. Learning by doing. We have created a brochure that explains all the ins and outs of the Fundamentals Course; feel free to download it here.

What works to design a choice: Bounded choice

So, what works then to design choice in a way it shapes positive behaviours? Next to the concept of bounded rationality, there is the concept of bounded choice (which I prefer to call bounded options as you may have guessed). Let’s look back at the paradox of choice again. It shows that having too many choices has been associated with feelings of unhappiness.

A greater variety of choices actually makes us feel worse.’

But on the other hand, it works the other way around too, and on the more positive side of things:

Limiting the number of options can lead to more satisfying choices.

Researchers did a meta-analysis comparing 99 scientific studies on choice overload. They found that choice reduction is most effective when:

Before we design a choice: Ethical considerations

From an ethical point of view, it is good to make a distinction between options and choice. We feel it can be a very effective Behavioural Design to help someone make better decisions by limiting an option, but you shouldn’t forbid a choice. So, in fact, you design choice by working with options. This is the essence of nudging. Let me illustrate the difference with an example.

Limiting the number of options or take out some options altogether has, for example, proven to be very beneficial in helping people who are struggling with being overweight. One very effective way to fight this is to change eating habits. A lot of interventions have been developed and tested to help people change their eating patterns. From adapting food labels to more affective nudges, for example, by promoting the taste instead of a particular food’s healthiness. From a meta-analysis, aggregating data from almost 96 behavioural experiments on successfully promoting healthy eating, the most effective intervention turned out to change the plate and cup size Taking an option (in this case, large 16 oz. cups) helped people eat less and still feel satisfied. Although you take away options with this intervention, you don’t take away the freedom of choice. People always have the choice to go for a refill or buy a second portion. Only, it turned out not many people do. By simply reducing options, you make it easier for people to change their behaviour.

Just one more argument against limiting freedom of choice (instead of options). We, as humans, are wired to want a sense of control and closely tied to this sense of control is our need for freedom and autonomy. If you do forbid a choice, you may, therefore, very well encounter adverse effects. People might start avoiding, ignoring or counterarguing. This is also why warnings backfire. We don’t like to be told what to do. It crosses our innate need for freedom. And if people are pushed into doing something, they push back. How many times did you change your mind or behaviour in your adult life because someone demanded you to do so? My parents and teachers still had that influence on me, but in daily life when we want to influence people, we need to allow for agency.

Want to shape behaviour and decisions?

Then our two-day Fundamentals Course is the perfect training for you. You will learn the latest insights from behavioural science and get easy-to-use tools and templates to apply these in practice right away!

Designing a choice: Behavioural change interventions

Time to turn human understanding into practice. What can we do to help people make better decisions and be more satisfied? I want to show you five behavioural intervention strategies to design for better choices:

Limit or remove options

Terminate products or services that are not doing well.

Organise options

Make categories or ease people into choosing from more options.

Frame options

Present information to someone in a way choosing becomes easy.

Help people to understand their personal preferences

Helping them limit options to the ones that fit them.

Offer expert advice

This way, people can ask a specialist to help them choose, outsourcing the decision.

Limit or remove options

How far you should limit options depends on the behaviour you are designing. If you want someone to click on a button on your website, it is better to have one clear option. If you want someone to pick a health regimen, it works to have three options, with your preferred option positioned in the centre, as people tend to gravitate to the middle. If you want someone to buy a specific product, it works to show two options of which the left product (in Western countries) is a decoy that is priced much higher than your target product. This higher-priced product will act as a mental anchor that makes people feel your product is a perfect deal. These are best practices from behavioural science, but it is always a matter of experimenting with what works best in your situation. One thing remains the same for every situation: Less is always more when shaping decisions and behaviour.

Organise options

However, you can make people more capable of choosing from more options. You just have to do it gradually. A research team at a German car manufacturer ran an experiment with the manufacturer’s online car configurator. Potential clients using the configurator had to choose from 60 different options to configure their entire car. Every option again consisted of sub-options. For instance, to pick your car colour, you had 56 colours to choose from, picking your engine also four options and so on. It seemed logical to have people select an ‘easy option first. For example, colour is something that most people have a set preference for. And then move to the ‘harder’ options like the engine. The experiment made half of the customers go through the configurator from many options (e.g., colour) to fewer options (e.g., engine type). The other half from fewer options to many options. The researchers found that they ‘lost’ the second group: They kept hitting the default button or aborted the process. The first group hung in there. They had the same information and the same number of options, only the order in which the information was presented varied.

If you start someone off easy, you can teach them how to choose.

Frame Options

Sometimes option reduction is a matter of framing. In other words, thinking about how to present information to someone. Maybe you have kids, and well, most kids aren’t big on eating veggies. Mine isn’t, anyway. We, as parents, often tell our kids: ‘Eat your peas’. You’ll probably have more success if you give your kids a sense of control, designing the options a different way. ‘Do you want to eat your peas or carrots first?’ It can also work in our professional life. Let’s say you are in negotiation with a talent you like to attract your team or organisation. Make sure you frame your negations in a way options are limited but still allow for autonomy. To make it more real: Often, negotiations come down to challenging the salary offer. Suppose you give someone the option to get awarded a higher salary, but you tie a condition to it. For example, sure, you can have a higher salary X, but it implies X fewer days off. Your candidate still has freedom of choice, but at the same time, you framed your offer as bounded options. Thus, prevented setting the stage for a limitless salary/bonus battle, nitpicking over secondary employment conditions. ‘It’s either this or that kind of framing.

Identify personal preferences

We have seen that when we experience option overload, we tend to rely on system 1 cues such as following the choices of others. If you can help someone identify their personal preferences, you can rule out a lot of options. This is why shopping bots or online filters really help us navigate through options. Once you have set your preference, you only get to see a selection of all available options.

Offer expert advice

A different way to reduce options is to outsource the decision process to an expert. In this case, we can learn from the healthcare domain. If you have a condition that can be solved with treatment A, B or C, most people follow their doctor’s advice for a specific treatment. He rules out some options for you. What if we could also provide trusted experts in other domains? If you know, you can rely on an exercise, nutrition, finance, education expert? That would save you a lot of option researching and go down a rabbit hole of endless possibilities. You could simply follow the lead of a trusted specialist.

To conclude, there is, in fact, an art to choosing. If you start to understand a bit more about the workings of the human mind this will give you far more control over successful outcomes. You can choose to be more successful, in fact. How’s that for a change? Doesn’t it spark your sense of freedom?

References (alphabetical):

Schwartz, Barry (2004). The Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less, Ecco.

Cover photo by Clay Banks

BONUS: free ebook 'How to Design a Choice: the art of choosing'

Especially for you we've created a free eBook 'How to Design a Choice: the art of choosing.' For you to keep at hand, so you can start using the insights from this blog post whenever you want—it is a little gift from us to you.

How do you do. Our name is SUE.

Do you want to learn more?

Suppose you want to learn more about how influence works. In that case, you might want to consider joining our Behavioural Design Academy, our officially accredited educational institution that already trained 2500+ people from 45+ countries in applied Behavioural Design. Or book an in-company training or one-day workshop for your team. In our top-notch training, we teach the Behavioural Design Method© and the Influence Framework©. Two powerful tools to make behavioural change happen in practice.

Suppose you want to learn more about how influence works. In that case, you might want to consider joining our Behavioural Design Academy, our officially accredited educational institution that already trained 2500+ people from 45+ countries in applied Behavioural Design. Or book an in-company training or one-day workshop for your team. In our top-notch training, we teach the Behavioural Design Method© and the Influence Framework©. Two powerful tools to make behavioural change happen in practice.

You can also hire SUE to help you to bring an innovative perspective on your product, service, policy or marketing. In a Behavioural Design Sprint, we help you shape choice and desired behaviours using a mix of behavioural psychology and creativity.

You can download the Behavioural Design Fundamentals Course brochure, contact us here or subscribe to our Behavioural Design Digest. This is our weekly newsletter in which we deconstruct how influence works in work, life and society.

Or maybe, you’re just curious about SUE | Behavioural Design. Here’s where you can read our backstory.