With this Behavioural Design Overview we want to help you to navigate through the Behavioural Design Blog. Our ambition with this blog is to explore how influence works by applying it to interesting real world problems. Most of these blogs appeared in Behavioural Design Digest, our weekly newsletter. You can subscribe to the Behavioural Design Digest here.

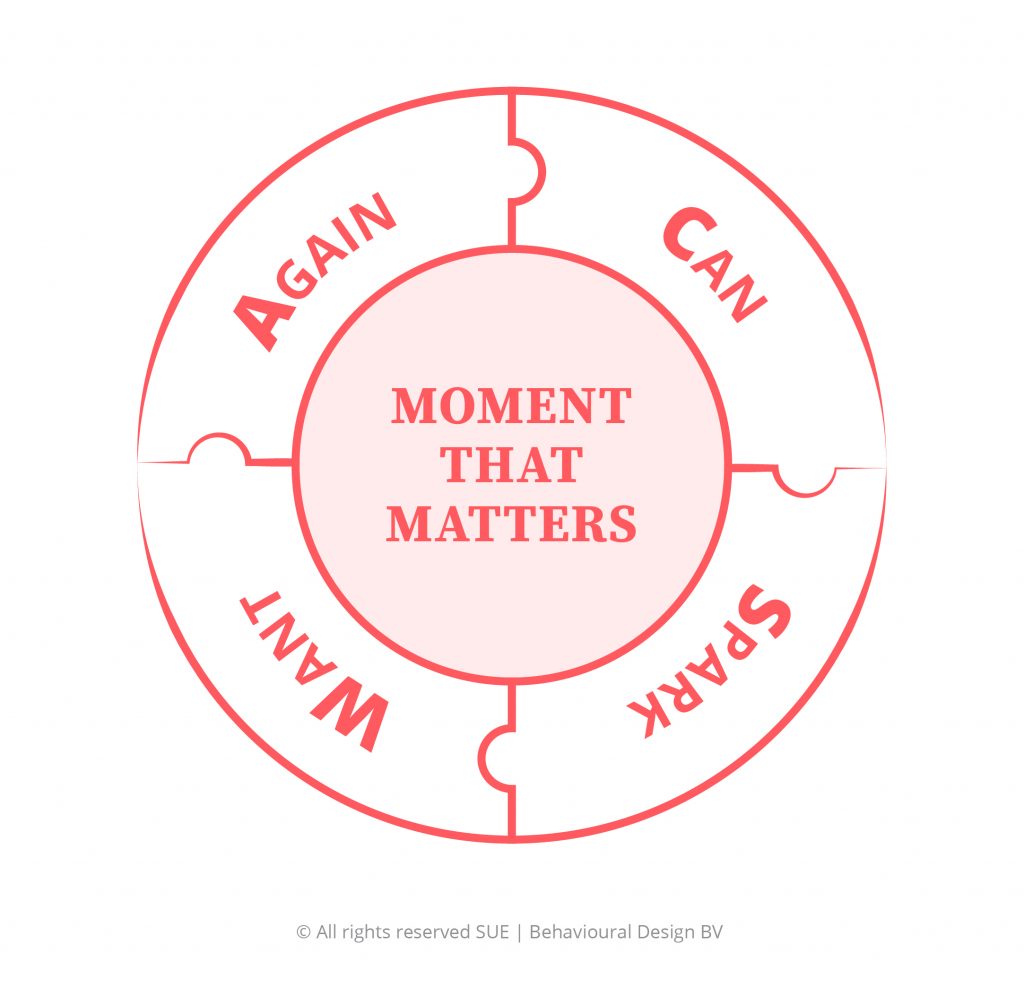

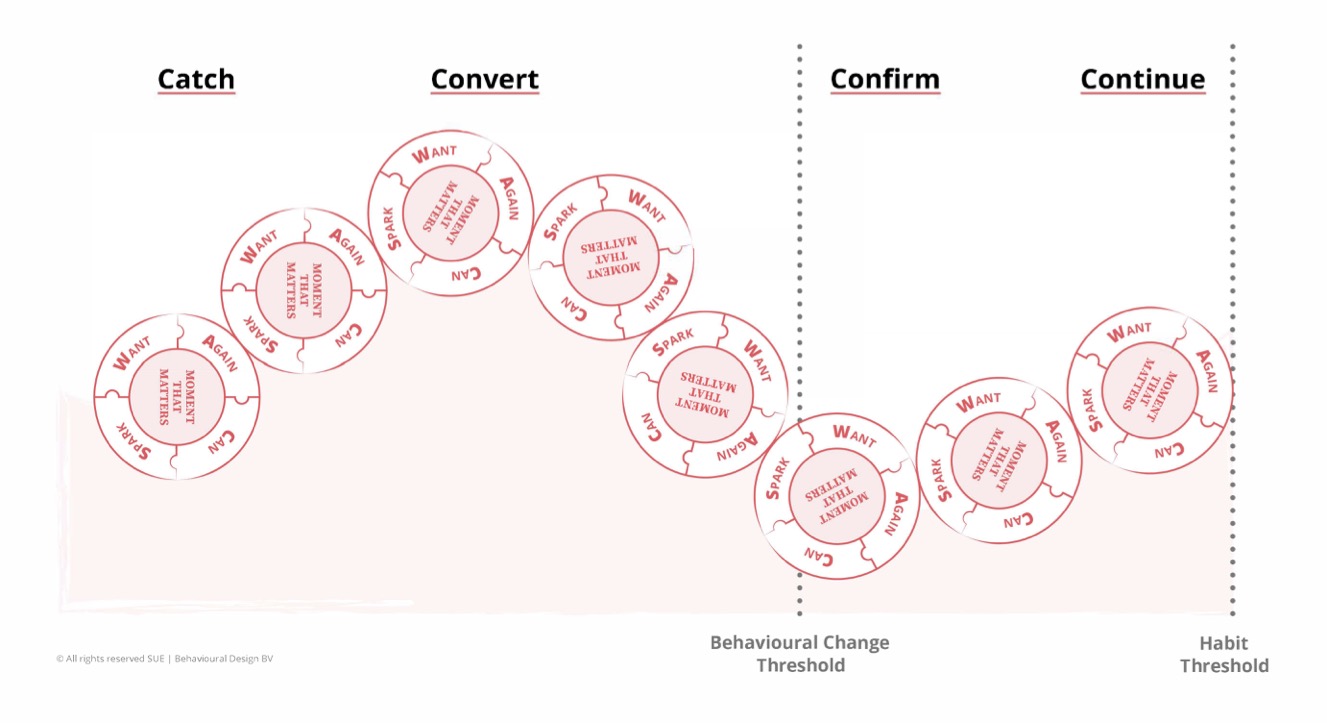

Everything we write is in line with SUE’s mission: ‘To unlock the power of behavioural psychology to help people make better decisions in work, life, and play’. This is the guiding principle behind our Behavioural Design Method© we teach in our Behavioural Design Academy and that we apply in our Behavioural Design Sprints. Curious to find out more about us? Meet us at ‘We are SUE‘ or buy our book ‘The Art of Designing Behaviour‘.

Happy exploring!

BONUS: free ebook 'How to Convince Someone who Believes the Exact Opposite?'

Especially for you we've created a free eBook 'How to Convince Someone who Believes the Exact Opposite?'. For you to keep at hand, so you can start using our insights whenever you want—it is a little gift from us to you.

How do you do. Our name is SUE.

Do you want to learn more?

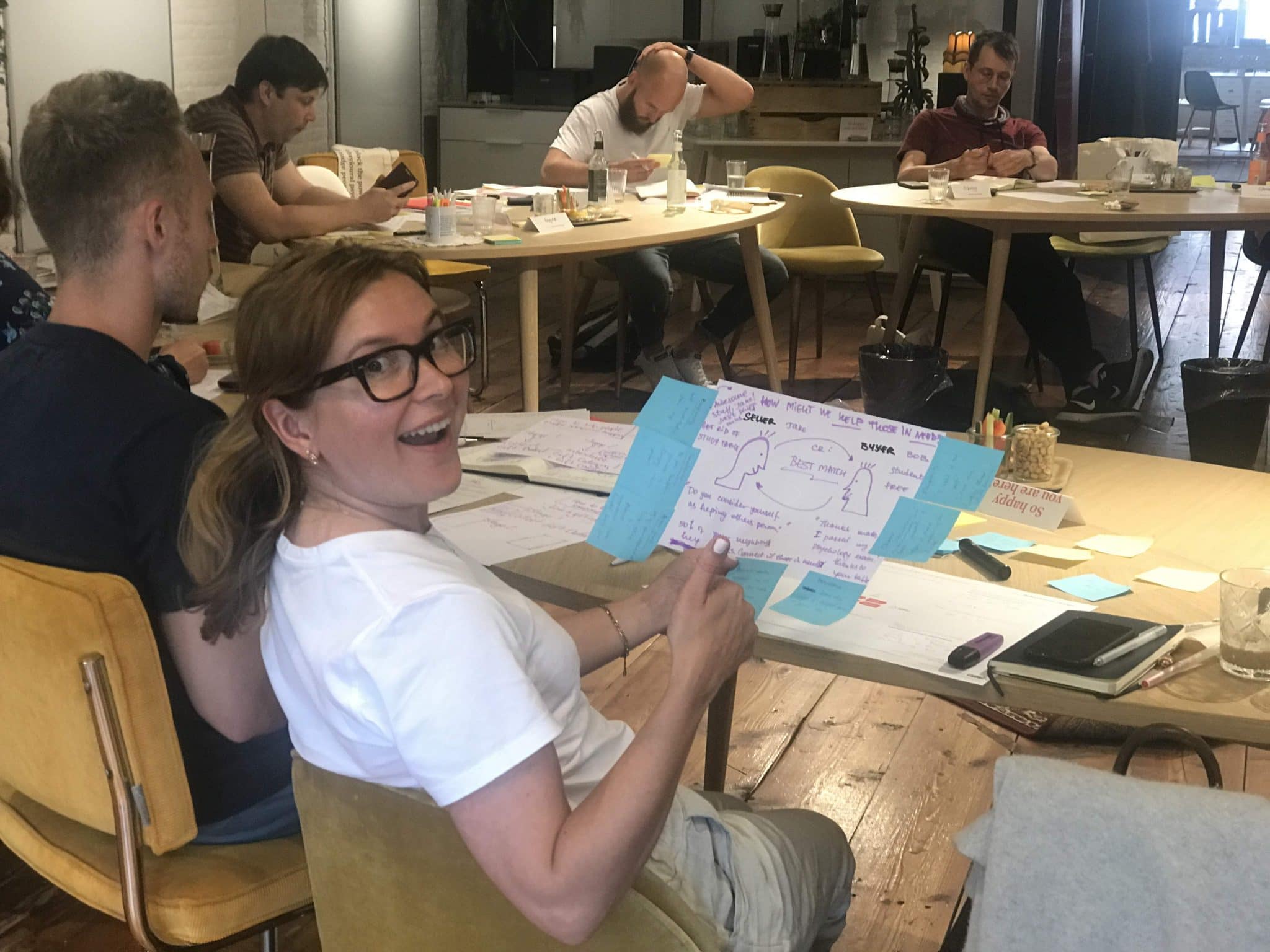

Suppose you want to learn more about how influence works. In that case, you might want to consider joining our Behavioural Design Academy, our officially accredited educational institution that already trained 2500+ people from 45+ countries in applied Behavioural Design. Or book an in-company training or one-day workshop for your team. In our top-notch training, we teach the Behavioural Design Method© and the Influence Framework©. Two powerful tools to make behavioural change happen in practice.

You can also hire SUE to help you to bring an innovative perspective on your product, service, policy or marketing. In a Behavioural Design Sprint, we help you shape choice and desired behaviours using a mix of behavioural psychology and creativity.

You can download the Behavioural Design Fundamentals Course brochure, contact us here or subscribe to our Behavioural Design Digest. This is our weekly newsletter in which we deconstruct how influence works in work, life and society.

Or maybe, you’re just curious about SUE | Behavioural Design. Here’s where you can read our backstory.