Did you know we treat money differently depending on where it comes from, where it is kept, or how we label it? In this blog post, I want to introduce you to the concept of mental accounting. A fascinating psychological phenomenon affecting many of our financial behaviours, such as the way we spent and save money or value things for which we’ve paid money. Understanding more about mental accounting could help us design better financial decisions and behaviours. And understand why some people seem to make financial decisions that don’t always seem to make sense or be in their best interest.

Mental accounting: How humans violate the economic theory

Mental accounting: How humans violate the economic theory

Why mental accounting is so fascinating is that it simply explains why 1 euro isn’t always 1 euro. From an economic theory perspective, this might sound foolish. The value of 1 euro and another euro on the same day is equal. We have a whole international money rate system in place that can tell you the exact worth of your euro at any precise point in time. In four digits. Also, economists believe that it shouldn’t matter if you have a 100-euro banknote or five 20-euro banknotes. It is the same amount of money, and you will spend it the same way; after all, they are exchangeable. However, psychological research has shown that humans often violate this rational approach to money.

This works may be easiest explained by an example described in the landmark paper of Richard Thaler (1), the author of the influential book ‘Nudge‘ and a Nobel prize laureate. Let’s say you have bought a ticket to a concert and it cost you 50 euros. You made your way to the concert venue, you have dressed up nicely, you have arranged a babysitter, and if you say so yourself: you look good. You are more than ready for the evening out that you have anticipated for weeks. You get to the entrance, reach into your pocket to find out that you have seemed to have lost your ticket. After going through all the stages of grief: denial, pain, anger, depression, acceptance, finally, hope kicks in as you see the ticket booth is still open. You quickly head over to the ticket booth to find out you don’t get your ticket reimbursed but have to pay another 50-euro for a new ticket, which is luckily still available.

Okay, same scenario, but just a bit different. You want to see that same concert, again you dress up nicely, sprayed on a bit of cologne because it is a special night out, after all, the same babysitter is there to attend to your kids, and you head over to the concert venue. When you go over to the ticket booth to buy yourself a ticket, you realise the 50-euro banknote you had put in your pocket to pay for the ticket fell out. After almost panicky going through all your pockets, reality sinks in. The 50 euros are gone. Luckily, the time tickets are still available; you have to get out another 50 euros to buy the ticket.

The interesting question is would you do so in both situations? From an economist perspective, the exact same situation: You have lost 50 euros, and you have to pay another 50 euros to attend the concert. So, there shouldn’t be a difference in the decision you make. However, Thaler’s research found that people in the first scenario are far more likely not to buy a second ticket, whereas people in the second scenario do.

If you lose cash, it turns out you’re willing to buy a ticket. If you lose a ticket, you do not want to buy a second ticket.

Would you like to know more?

We have created a brochure telling you all about the details of the Behavioural Design Sprint. Such as the set-up, the investment, the time commitment, and more. Please, feel free to contact us any time should you have any further questions. We are happy to help!

Mental accounting: What is it, and how do people do it?

Mental accounting explains this story. What is mental accounting? It is the idea that people tend to label money. And the moment you label money differently, it gets spent differently.

People tend to label money. And the moment you label money differently, it gets spent differently.

So, how do people mentally account? Well, there are several different ways in which people put money into different psychological categories:

- You could mentally account by purpose. You can allocate money to a specific product or service, or objective. This is what happened with the concert ticket. It was assigned to the concert, losing the ticket felt we had lost out on the concert in our mental account. You think you are already in the ‘red’. You are not going to make it worse by spending even more money on the same product. But allocating money to savings is another way to mentally account by purpose.

- You could mentally account by time. You could say I will spend X amount per week or budget that many euros each month.

- You could mentally account as a function of how you have earned money. If you have put in many hours of hard work to make your money, you will spend it differently if you have earned it by winning a lottery.

Mental accounting: The sunk cost effect

Mental accounting: The sunk cost effect

Let’s take a look at another way mental accounting influences our behaviour. Let’s get back to the concert. Let’s say you have the ticket, only this time there is a difference in how you acquired that ticket. In the first scenario, you have prepaid for it; in the second scenario, the ticket was a gift. Imagine this situation, on the evening of the concert, there is this raging blizzard storm, and the concert is a two-hour drive away from your home. Would you go to the concert in both scenarios? If you would rationally think about it, you wouldn’t go in both situations. It is much safer to snuggle up comfortably on your couch. However, most people who have prepaid the ticket will make an effort to drive a few hours through a blizzard storm to attend a concert that they (only) paid $20 for. This is caused by a phenomenon known as sunk cost fallacy.

If people have spent effort, time or money on something, they will commit to the behaviour related to it; otherwise, they feel they lose out.

The moment you spend money to consume something in the future, our sunk cost effect of mental accounting kicks in. The moment you prepay, you have a deficit in your account. If you cannot consume, then you have to close your account in red. It’s like making a loss. People don’t like making losses, so they rather get what they paid for than perhaps make a better decision not to consume something. For example, if people spent 60 euros on a four-course dinner, but they are already full at the third course, most of them will eat dessert anyway. I paid for it! It feels like a loss not to go or not finish all your plates.

Another example made famous by Richard Thaler is about a man who joined a tennis club and paid a $300 membership fee for the year. After just two weeks of playing, he develops a case of tennis elbow. Despite being in pain, the man continues to play, saying: ‘I don’t want to waste the $300.’ (2)

The sunk cost effect becomes a huge motivator of consumer behaviour.

However, the intensity of the sunk cost effect isn’t always the same; it depends on how closely the cost and benefit are connected. Let me give you an example of how this works. Let’s say you love skiing and you have booked yourself a trip to the French Alps. You got yourself a four-day ski pass giving you access to all the ski lifts for the four days at the costs of € 160. You enjoyed the first three days, and then all of a sudden, the weather conditions change dramatically: Big snows, fog, heavy winds. No skiing conditions that will bring joy. The same scenario, but now you have bought four separate tickets of € 40 with which you can hit the slopes for four days. In which situation would you go out skiing on the fourth day?

This was researched (3), and it showed that people who bought the one ticket would be more prone to stay in. However, the people who had four separate tickets were far more inclined to go out and ski anyway. They felt the €40 burn in their pocket (cost) and want to experience the benefit (skiing). The all-inclusive ticket is, in fact, a form of price bundling. This leads to a ‘decoupling’ of costs and benefits. The effect being it reduces someone’s attention to sunk costs and decreasing a consumer’s likelihood of consuming a paid-for service. In other words,

Price bundling affects the decision to consume.

Now, it becomes interesting how we can use these insights to design for better choice and positive behaviour.

BONUS: free ebook 'Mental Accounting: How Money Works in our Mind''

Especially for you we've created a free eBook 'Mental Accounting: How Money Works in our Mind'. For you to keep at hand, so you can start using the insights from this blog post whenever you want—it is a little gift from us to you.

Mental accounting: Using it for better decision-making

Mental accounting: Using it for better decision-making

Being aware of the human tendency to engage in mental accounting and being affected by the related sunk costs effect can help us develop behavioural interventions that can help people make better decisions. I want to end this blog post with an example of how this might work.

A lot of people find it challenging to spend less money than intended. You can make this easier for them by partitioning. How does it work? Let me illustrate this with a real-life example that took place in India. In India, there are quite some low-income households with very little spare cash. Salaries are often paid in cash, making it very easy for family providers to spend it, for instance, in the bar, after a hard days’ work. Still, people also needed money for the children’s upbringing, for example.

Those households typically earned 670 rupees per week (£6,60 or $11,20), and most families only managed to put aside 5 rupees per week (0,75%) (4). The intervention they did is divide the money into envelopes before handing it over to the beneficiary and partitioning it beforehand. It increased the savings rates to 4% (27 rupees per week)(5). What made it even more successful is putting a visual reminder on the envelopes. So, for example, a picture of their children on the envelope contained money for their upbringing.

You could also use this for yourself. We are also more reluctant to spend money we have already mentally allocated for savings. You can distribute very physically, like the envelopes, but think about labelled jars in which you divide your household money. Viviana Zelizer, a sociologist at Princeton, calls this ‘Tin Can Accounting’ (6). The more digitally savvy translation of this is the digital saving buckets many banks offer nowadays, in which you can allocate your savings to specific goals. It will be harder to withdraw money from an ‘ultimate wedding dress’ or ‘summer family holiday’ bucket than from a general savings account.

Summary

We, as humans, often make very emotional decisions when it comes to money. It largely depends on how we have earned, labelled or how our money is kept, how we will treat money and how we value what we bought with the money. This largely influences our behaviour. A euro isn’t always a euro, and a dollar not always a dollar. It may sound illogical, but it will make perfect sense once you understand the concepts of mental accounting and the sunk cost effect. We need to take these psychological phenomena into account if we want to help people make better decisions.

Cover visual by Kelly Sikkema on Unsplash.

How do you do. Our name is SUE.

Do you want to learn more?

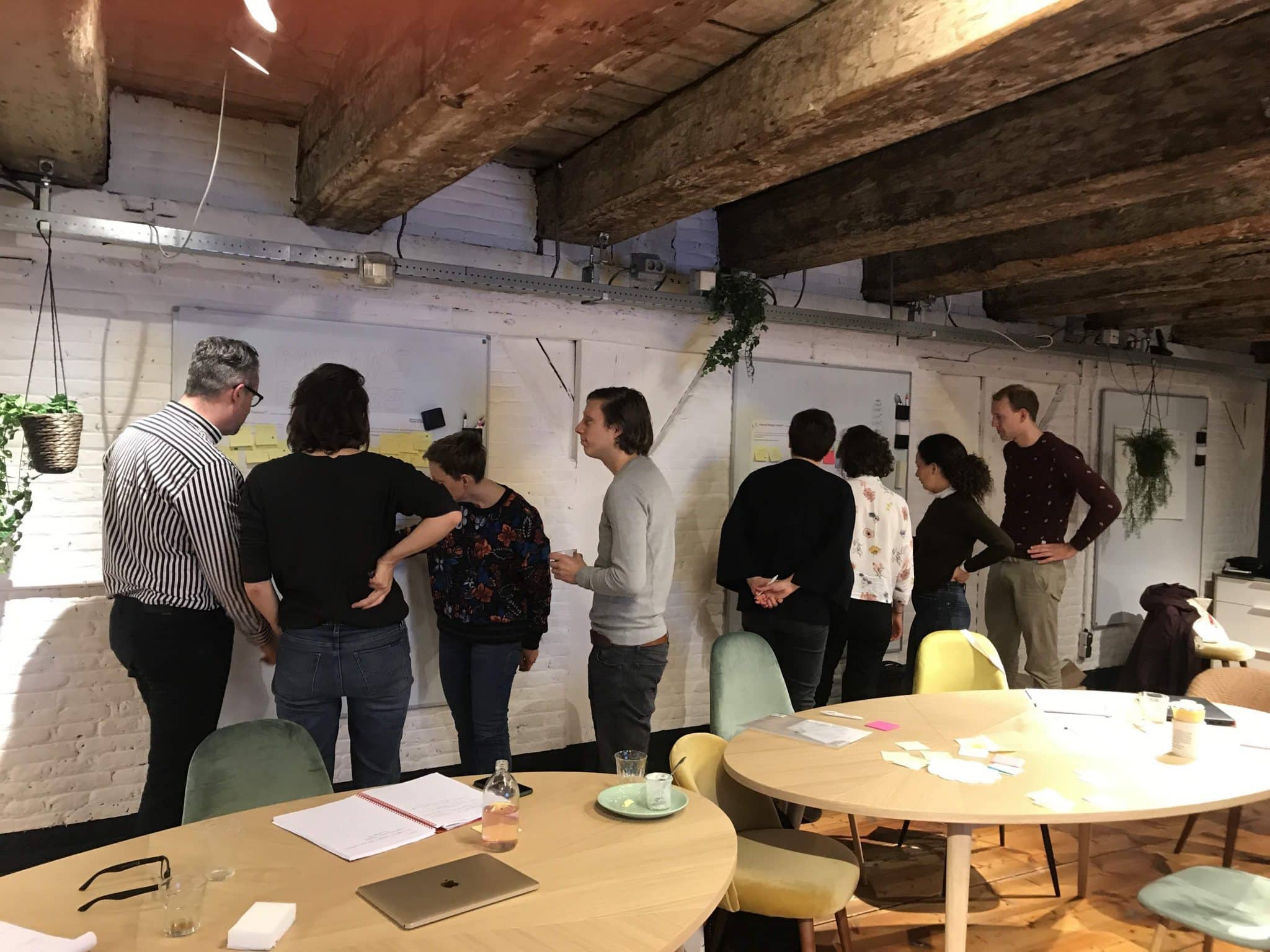

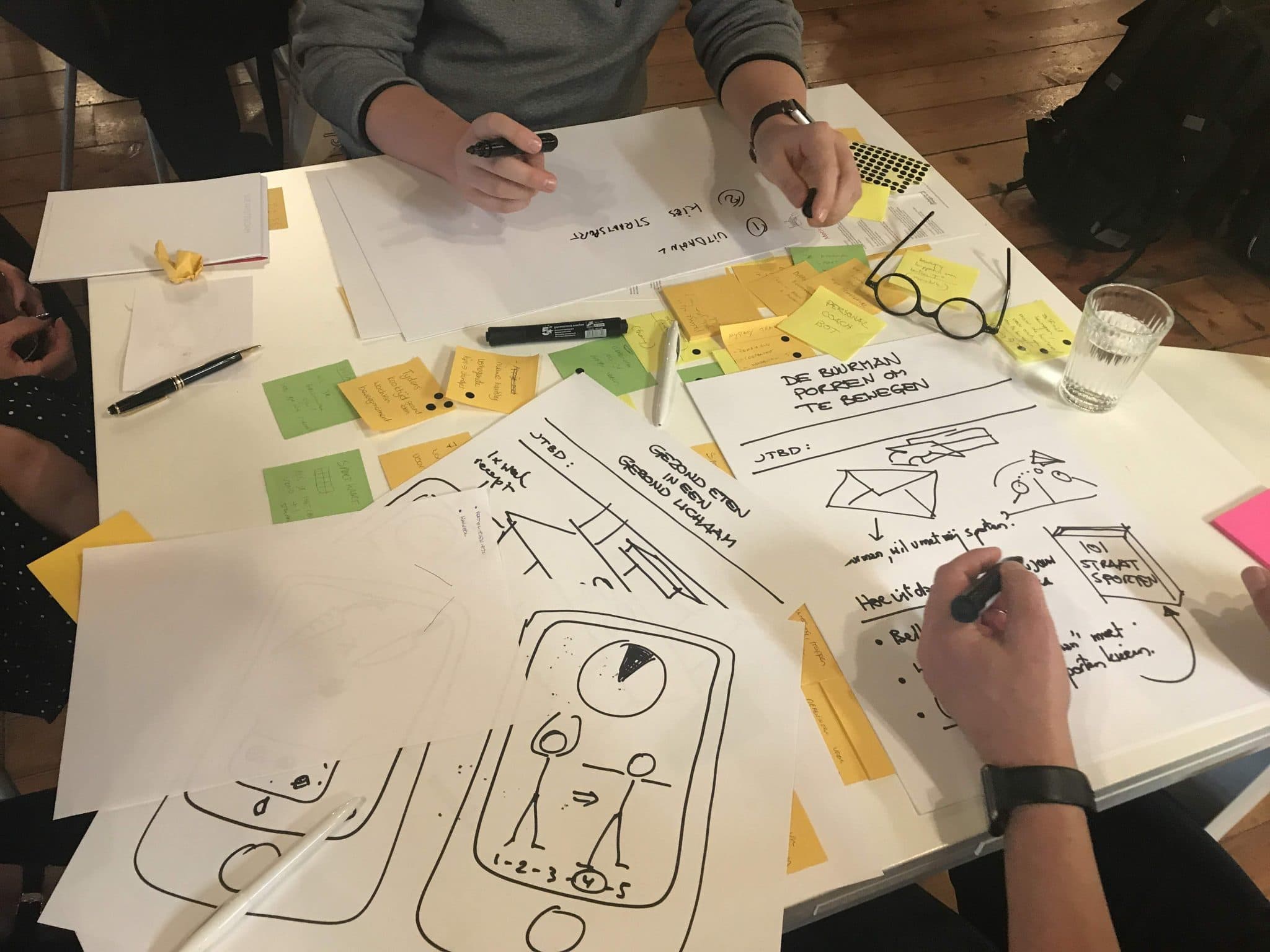

Suppose you want to learn more about how influence works. In that case, you might want to consider joining our Behavioural Design Academy, our officially accredited educational institution that already trained 2500+ people from 45+ countries in applied Behavioural Design. Or book an in-company training or one-day workshop for your team. In our top-notch training, we teach the Behavioural Design Method© and the Influence Framework©. Two powerful tools to make behavioural change happen in practice.

Suppose you want to learn more about how influence works. In that case, you might want to consider joining our Behavioural Design Academy, our officially accredited educational institution that already trained 2500+ people from 45+ countries in applied Behavioural Design. Or book an in-company training or one-day workshop for your team. In our top-notch training, we teach the Behavioural Design Method© and the Influence Framework©. Two powerful tools to make behavioural change happen in practice.

You can also hire SUE to help you to bring an innovative perspective on your product, service, policy or marketing. In a Behavioural Design Sprint, we help you shape choice and desired behaviours using a mix of behavioural psychology and creativity.

You can download the Behavioural Design Fundamentals Course brochure, contact us here or subscribe to our Behavioural Design Digest. This is our weekly newsletter in which we deconstruct how influence works in work, life and society.

Or maybe, you’re just curious about SUE | Behavioural Design. Here’s where you can read our backstory.