Of all ‘wicked design problems’, motivating people for climate action and designing for sustainable behavioural change are topics many people at SUE are passionate about. When Tom recently suggested Futerra’s paper Sizzle to me, I dove right in, eager to find additions to our toolbox. It’s an excellent read and it makes a persuasive case for a new way of ‘selling’ climate action: instead of selling the negative necessity, we have to sell the positive results of action. Not the hunger, not even the sausage, but the sizzle. Being half-German it invoked lots of appealing memories of grilling bratwurst, so I was all aboard.

We know what dystopias look like, but we lack images of a green utopia.

We know what dystopias look like, but we lack images of a green utopia.

Lame jokes aside (it’s a cultural thing), it reminded us of a podcast we made some time last year (sorry, Dutch only), in which we discussed climate inaction and stumbled upon the realization that we badly lack utopian visions of the future in popular culture for behavioural change in sustainability. I really don’t know of any book, film, game or piece of art from the last couple of decades that plays out in a positive future. Albeit in many different variations, it’s pretty much all cyberpunk or otherwise dystopian and apocalyptic visions and the message is simple: one way or another, in the not-to-distant future we’re gonna fuck it up. Big time.

That is a symptom of a lack of positive imagination within our cultural avant-garde and a serious problem for the rest of us. Why invest in a future that’s doomed? Why take part in process of change if you don’t have any mental pictures of the exciting and bright future that it could lead to? It’s hardly a surprise that indeed many people simply don’t: compared to where they fear change will lead them, they like where they are just fine, and inaction or worse is the result. So yes: I think Futerra makes a meritorious point. Climate action must be framed in a far more positive way if we are to motivate people for behavioural change.

Yet, for some reason it didn’t sit with me well.

Aren’t we just yet again preaching to the choir?

Isn’t this all a – granted, greatly – improved version of a still fundamentally flawed approach, which is that through communication we should try to achieve a level of aspirational motivation among the population to contribute to a sustainable way of life, and that behavioural change will follow from that? And won’t it, when that inevitably yields limited results, still turn out as a way of preaching to the converted, but with a nicer preach? Isn’t it therefore essentially still focused on fulfilling the emotional and social jobs-to-be-done of the activist, rather than purposefully designing large scale behavioural change? In other words, use behavioural psychology to drive real behavioural change?

Now, I don’t mean this to feel harsh. In fact, the authors explicitly invite a behavioural perspective on their approach. Here it comes.

Would you like to leverage behavioural science to crack your thorny strategic challenges?

You can do this in our fast-paced and evidence-based Behavioural Design Sprint. We have created a brochure telling you all about the details of this approach. Such as the added value, the deliverables, the set up, and more. Should you have any further questions, please feel free to contact us. We are happy to help!

Intention is a bad recipe for motivating people for climate action.

One concept from behavioural psychology that’s particularly interesting in this regard to behavioural change is the intention-action gap. As a rule, people have a hard time acting up on their intentions. More than often, people even behave in a way that directly contradicts them. This happens at the level of individual behaviour (just think back to everything you’ve intended to do to live more healthily and reflect on how much of it you’ve actually accomplished), and definitely at the level of collective behaviour as well.

We love our local shops, but with every purchase on Amazon, we give them the finger.

A good example is the struggle that local retailers have in their competition with the big webshops. Both individually and collectively, we all want flourishing city and town centers, with lots of locally owned shops and cozy restaurants and such, but with every passing day we buy more of our stuff at a small number of big webshops. With every purchase at Amazon, BOL or Zalando, we’re tightening the rope around those local entrepreneur’s necks, and yet we keep doing it – even employees of the local shops.

Why? Because it’s simply easier and cheaper. Individually it’s the better decision.

Even when motivation to support local entrepreneurs peaked during the first COVID-lockdown, Dutch online giants BOL and Coolblue did better than ever and Amazon managed to very successfully enter the Dutch market. We heedlessly make choices that completely contradict our intentions, let alone our larger aspirations. Behavioural psychology at work?

In other words, even when exactly the right messaging manages to build up peoples’ intention to contribute to climate action, it’s not at all likely that this will lead to matching behaviour. That’s a sobering insight which, especially when it comes to climate action, we must be very clear-eyed about. The stakes are too big.

How might we break this behavioural pattern?

Apparently, many behaviours emerge, even if they lead to an outcome that people aren’t motivated to achieve – in fact even if it’s an outcome they’re motivated to prevent. Current consumer behaviour will lead to a web-only retail sector, dominated by a handful of giants. Nobody wants it, but it’s the outcome of our daily choices, which are heavily determined by convenience and costs.

This can work to our advantage.

Many of the most fundamental changes in our way of life have occurred over time, without people having some clear end goal in mind, or even an expectation of what the end result of the road they were on could be, or even a desire to look further than the immediate short-term. When steam machines and electric light bulbs were first put to use, nobody had the ermergence of the industrialised welfare state in mind. When people ordered their first modem, nobody had their sights on the cyborg-like relationship we have with our smartphones a couple decades later. What kind of a way of life these first behaviours would eventually lead simply to didn’t matter. What mattered was that that machine, that lightbulb, that modem, and every small steps that followed, made those peoples’ lifes a little bit easier, more convenient, or in another way humanly more pleasing, in that moment.

Developing a climate neutral way of life is a fundamental change of a similar order, and for the population at large, climate neutrality will similarly be an emerging property: the outcome of their choices, rather than the goal of their choices. This is the only way forward is to influence group behaviour for climate change.

Want to learn how to use behavioural science to tackle societal challenges?

The Fundamentals Course is perfect for you. You will master a hands-on method to tackle even wicked challenges using applied behavioural science. Mind-shifting know-how that is made 100% practical.

The solution: Make sustainable choices more desirable.

Hence to motivate people for climate action, we shouldn’t put too much of our collective creative energy into convincing people of the larger goal and building up their motivation to contribute to climate action, and put nearly all of it into simply designing those incrementally better everyday choices. If we want to design for genuine behaviour change, it means innovating on sustainable products, services and behaviours, so that they’re increasingly convenient or in many other possible ways the more fulfilling choice.

Tesla doesn’t want you to drive electric for the environment, but because they offer an exciting driving experience. Beyond Meat doesn’t want you to go vegan on your hamburgers, they want you to eat the juiciest hamburger in the world, which happen to be vegan.

That requires above all ruthless, methodical empathy for those humans whose behaviours and choices we want to change. Don’t wash away their anxieties, comforts, pains and deep-rooted human needs and desires in service of climate neutrality – start with them. In fact, I’d put it even stronger:

The only way to achieve climate neutrality in time is to be ruthlessly empathetic with the people whose behaviour we need to change.

Tim is a Behavioural Design Lead at SUE. In his spare time, he’s a councillor for the Dutch Liberal Party at the City of Rotterdam

He recently co-authored a book with Klaas Dijkhoff, Group Chairman of the Dutch Liberal, in which they plead for an optimistic renaissance based on the fresh liberal concept.

Cover Photo by Markus Spiske

Read or Watch more

Insights about Sustainability

How do you do. Our name is SUE.

Do you want to learn more?

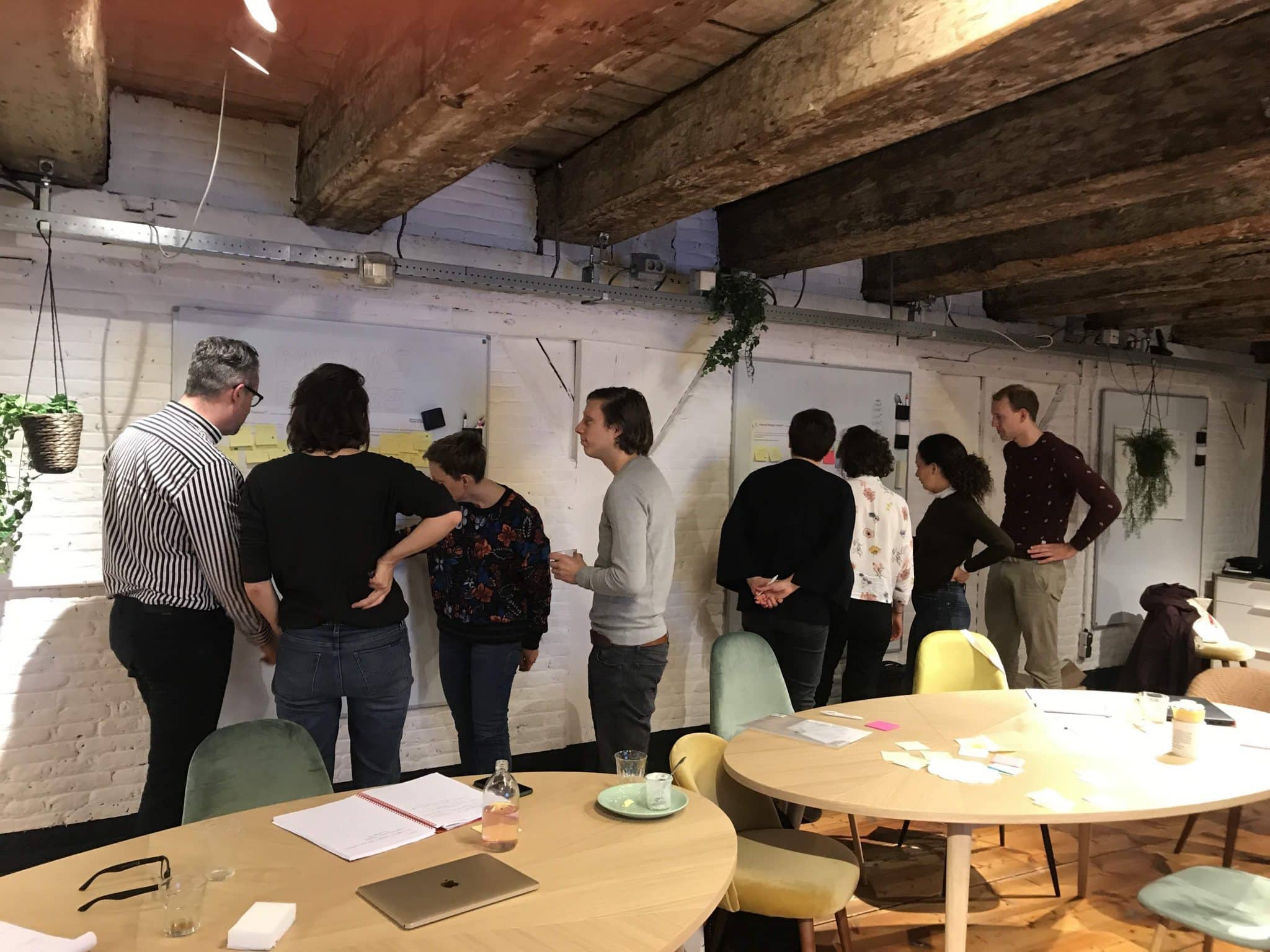

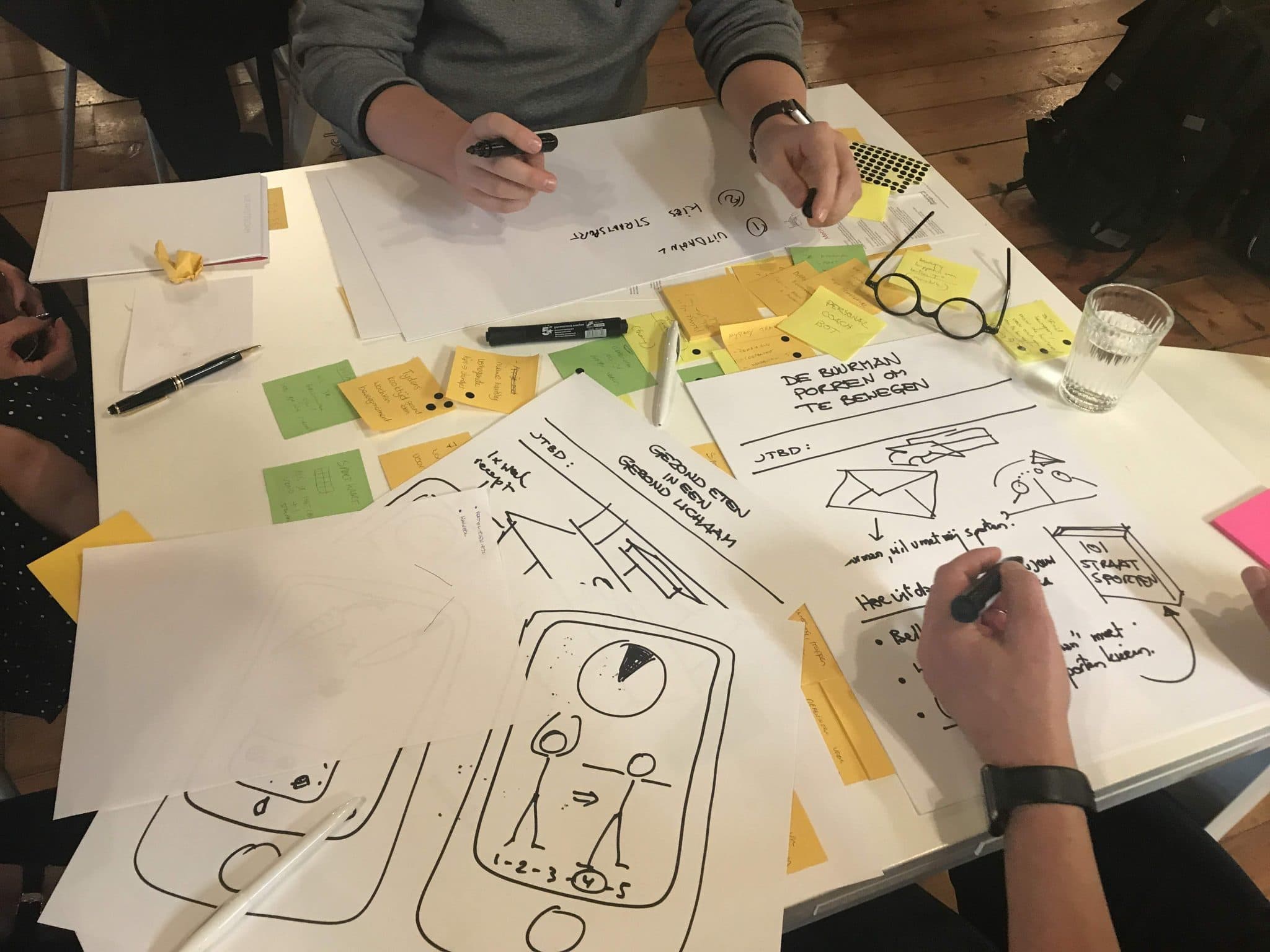

Suppose you want to learn more about how influence works. In that case, you might want to consider joining our Behavioural Design Academy, our officially accredited educational institution that already trained 2500+ people from 45+ countries in applied Behavioural Design. Or book an in-company training or one-day workshop for your team. In our top-notch training, we teach the Behavioural Design Method© and the Influence Framework©. Two powerful tools to make behavioural change happen in practice.

You can also hire SUE to help you to bring an innovative perspective on your product, service, policy or marketing. In a Behavioural Design Sprint, we help you shape choice and desired behaviours using a mix of behavioural psychology and creativity.

You can download the Behavioural Design Fundamentals Course brochure, contact us here or subscribe to our Behavioural Design Digest. This is our weekly newsletter in which we deconstruct how influence works in work, life and society.

Or maybe, you’re just curious about SUE | Behavioural Design. Here’s where you can read our backstory.