If there would be an easy and friendly way to significantly improve how well people in your office wash their hands between touching all of the common surfaces such as doorknobs, the coffee machine, and the fridge, would you want to have it? Then right on and get it. With compliments of the Dutch government.

The rules are back

The rules are back

You’ve heard it: the basic hygiene rules have been reintroduced by the government to suppress the spread of the virus. Two years ago people would’ve laughed uncomfortably at such a sentence. Right now, we all know what it means. Get tested and stay at home if you have symptoms, work from home if you can, wear a face mask in public places, keep your distance, cough in your elbow, and wash your hands. We can dream it, and the vast majority of us support and will conform to these norms – mostly.

Saying isn’t doing

Throughout the pandemic, the Dutch public health institute RIVM has kept track of public support of and compliance with the various norms. Its insightful dashboard shows that for most norms, support and compliance have differed significantly. For instance, 84 percent supports staying at home when having symptoms, but only 55 percent reports actually doing it. That’s a noteworthy difference, yet for behavioural designers, such a gap between intention and action would have been expected.

There’s one such disparity on the dashboard, however, that will take even the most experienced old fox among you by surprise.

“83 percent support washing hands in accordance with the guidelines, and a mere 32 percent actually do it.”

They just don’t

What makes this even more remarkable, is that none of the explanations which typically help us understand intent-action gaps are applicable. There are no obvious conflicting motivations, like when social jobs-to-be-done supersede the intention to stay at home with symptoms. There are no overwhelming practical problems: hands can be washed in every bathroom, toilet or pantry at no cost to the individual involved. And it doesn’t really involve resisting any kind of conflicting temptation.

People support it. They want to do it. They can do it. But they just don’t.

So – how do we change that?

The challenge

This is the challenge we were approached with by Majka van Doorn (who by the way happens to be an alumnus of our Behavioural Design Academy) and her team at DGSC-19, a Rijksoverheid-directorate focused on medium-term measures to suppress the spread of the virus, together with the RIVM. Hand washing is incredibly effective in reducing the spread of pathogens and is particularly important in office environments, where people touch many of the same surfaces. Whether elevator buttons, doorknobs, phones, coffee machines, fridges, food in the cafeteria, or copy machines; they’re all great for the spread of viruses when hand washing discipline is low. It’s obvious why the government would want to come up with an effective intervention, especially now more and more people have begun working at the office again. And boy, did we deliver.

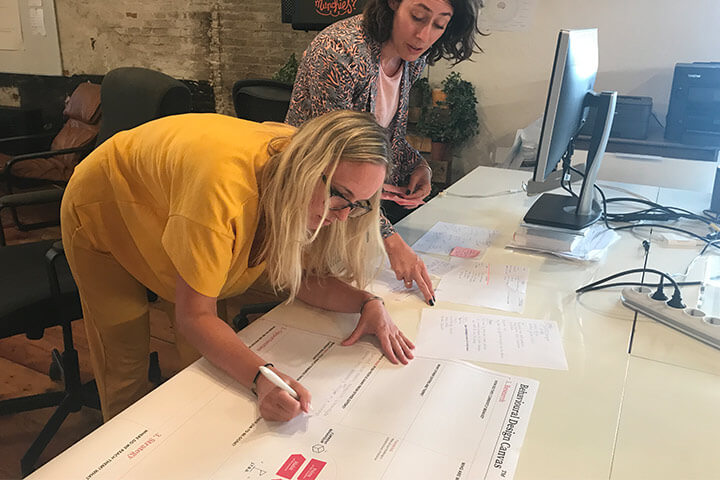

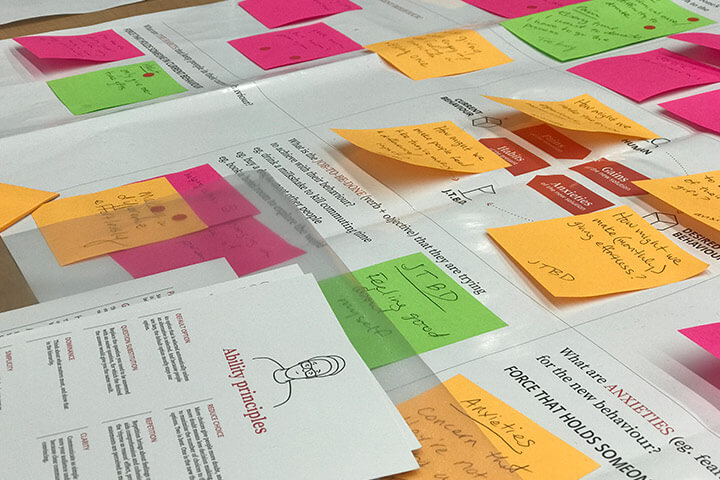

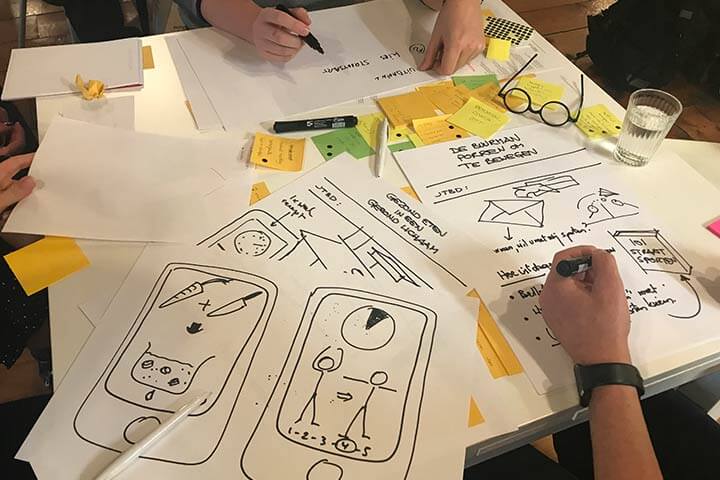

In a custom Sprint that was set up to start creating and testing and get practical as quick as possible, we first rapidly worked our way through a truckload of reports on attempts in other countries to tackle the same behavioural challenge, dived in the available data on the Dutch situation, and filled up the Behavioural Design Canvas. In two creative sessions we then designed five intervention strategies that we thought should work, and with our partners from the Rijksoverheid we selected three of them to prototype with the target group. With some adjustments, the combination of the three appeared to be a comprehensive intervention strategy, and merited a full-scale field test to measure real effect on behaviour.

Download the SUE hand washing guide

The name SUE comes from the song 'a boy named SUE'. Sing the song while washing your hands the correct way!

Behavioural interventions

1. Reframing. The first element is to reframe hand washing. The framing that occurs naturally through the current public discourse is that hand washing is something you do to prevent becoming ill or spreading illness. If you’re not fearful of that, you might still consciously support the measure in general, but you won’t subconsciously be triggered to wash hands enough throughout a day yourself. And as most behaviour occurs automatic, this then simply won’t.

Using a tool that’s great to instantly test framing effects, we designed a set of thirteen posters that in a friendly way reframe hand washing and connect it with food and other peoples’ hands, and the simple message: nicer with clean hands. Each poster visualises a specific situation and should be placed contextually relevant.

2. Visual cues. The second element is to provide simple and clear visual cues, in the form of colourful stickers, that toilets are not just a place where you relieve yourself, but where you can also wash hands. If motivation and ability are high enough, then sometimes all that’s needed is a well designed and placed spark.

Morover, with another set of visual interventions we attempted to insert hand washing into the arriving-at-the-office sequence that for most people is very habitual. When you’re in the pantry to get coffee, first wash your hands. You’re there anyway.

Astoundingly effective

The field-test, which we set up in partnership with our partners from DGSC-19 and RIVM, in a government office building in Rotterdam consisted of a weeklong measurement before interventions were placed, and then a weeklong measurement within four testing conditions. Soap usage was used as a proxy for hand washing. And the results were astounding: hand washing increased with up to 165 percent, going from an average of 2,8 times hand washing per day to 7,4 times a day. And what’s more: test persons did not experience the interventions as annoying. In fact they found them very useful for other people. Great!

Get more detailed information.

Download our Behavioural design Sprint brochure telling you all about the ins and outs of the sprint in detail. Please feel free to contact us suppose you would like some more information. We gladly tell you all about the possibilities.

In conclusion

These interventions clearly make a huge difference, and that just goes to show that don’t always need a big flashy campaign to change behaviour. You just need to find and hit the right nerve as simple as you can. And here’s the best thing: you’ll have to print ‘m yourself, but the posters and stickers are free for you to use.

One last thing: do make sure that there’s enough soap available. Your colleagues are gonna want it.

How do you do. Our name is SUE.

Do you want to learn more?

Suppose you want to learn more about how influence works. In that case, you might want to consider joining our Behavioural Design Academy, our officially accredited educational institution that already trained 2500+ people from 45+ countries in applied Behavioural Design. Or book an in-company training or one-day workshop for your team. In our top-notch training, we teach the Behavioural Design Method© and the Influence Framework©. Two powerful tools to make behavioural change happen in practice.

You can also hire SUE to help you to bring an innovative perspective on your product, service, policy or marketing. In a Behavioural Design Sprint, we help you shape choice and desired behaviours using a mix of behavioural psychology and creativity.

You can download the Behavioural Design Fundamentals Course brochure, contact us here or subscribe to our Behavioural Design Digest. This is our weekly newsletter in which we deconstruct how influence works in work, life and society.

Or maybe, you’re just curious about SUE | Behavioural Design. Here’s where you can read our backstory.