Conspiracy theories are a puzzling testimony to several peculiarities of our brain and the inner workings of the human psyche. However, they are omnipresent and have accompanied us throughout history. Whether it is 9/11, moon landings, the murder of Kennedy, or Covid-19, key societal events have rarely escaped a certain ‘conspiracy appeal’. Although they have been around for centuries, the ease with which we can share them today has given conspiracy theories incredible traction. So, what makes conspiracy theories so appealing to some, why do people believe them, and is there a way to protect us from their potentially detrimental effects?

Misinformation or conspiracy?

Let’s clarify first, conspiracy theories might easily -but wrongly- be equated with misinformation. This however is not the same thing. Believing a Covid vaccine doesn’t work isn’t a conspiracy theory. It’s just being misinformed. For something to be a conspiracy there need to be two things. First, there need to be two or more people involved (conspirators) and second, they need to have a secret or hidden plot (the conspiracy). For instance, stating the Chinese government launched the covid-19 virus to be able to inject bio trackers in the population or claiming that the CIA was directly involved in the murder of Kennedy ‘is’ a conspiracy theory.

Such theories trigger numerous questions. Where do they come from, who benefits, which people are prone to fall for them and why do they do so? And even more importantly, how should we deal with these theories and their followers.

Evolution made us skeptical

Before we go into the psychology of conspiracy theories let’s look at this phenomenon through the lens of evolution theory. Evolution hardwired us to be at least a bit skeptic and doubtful. There is a very logical explanation for this: it is called natural selection. During our evolution as a species, we were confronted with many dangers. Now consider the effects of a false negative versus a false positive assessment. Imagine I wrongfully think there is a predator (false positive): in that case, my prudence wasn’t really needed but it didn’t do any harm either. Now consider the reverse situation. A false negative, thinking there wasn’t any danger, while there was a predator: this imprudent assessment got you killed. It therefore seems fair to presume that an overly naïve community that always gave it the benefit of the doubt would be rapidly decimated.

“As a species it seems, a certain level of distrust and skepticism pays off.”

It translates into an ongoing inclination to be on the lookout for hidden dangers or plots. It seems, at least biologically, sound. In addition, there HAVE been many exposed conspiracies. The abundant proof throughout history of conspiracy ploys adds support to the notion that the ‘idea’ IS plausible. After all, didn’t we learn afterwards that America had a weapon deal with Iran, that the Belgian government did impose false testimony on its journalists during the Chernobyl disaster or that Nixon did commit the Watergate fraud? History shows some skepticism is merited.

BONUS: free ebook 'Confirmation Bias: how to convince someone who believes the opposite'

Especially for you we've created a free eBook 'Confirmation Bias: how to convince someone who believes the opposite.' For you to keep at hand, so you can start using the insights from this blog post whenever you want—it is a little gift from us to you.

Three forces that drive conspiracy theories

1. Cognitive bias

To complicate matters further our human psyche adds three additional forces that trigger us to take conspiracies seriously. The first component has to do with our desire -but limited ability– to understand the world we live in. We have developed several psychological short cuts to help us makes some sense of the world around us, but these mechanisms can bias our reasoning too. Some of our shortcuts lead us to fall far conspiracy ploys.

For instance, our proportionality bias makes us believe that big events need to have big causes. And our intentionality bias leads us to look for cause, meaning, and intent, also when it isn’t there.

To make things worse, our species is particularly tuned to look for patterns: it’s all connected, man! This desire to understand, pushes us towards narratives that provide meaning. An interesting narrative that satisfies our inner need to grasp the complexity of our lives is too attractive to ignore.

2. Group psychology

Group psychology adds another layer of appeal. Having something interesting to share within the in-group makes a person more valued and prominent. This attention-seeking behavior has been linked with an inclination towards narcissism (both on the individual as on collective levels). Clearly, social motives play a big part in the distribution of conspiracy ploys: remember for instance the appeal of the (false) proposition that there weren’t any Jews killed in the 9/11 attacks, a conspiracy rationale that was particularly prominent in Muslim communities.

3. The need to belong

And finally, several existential anxieties drive people to believe conspiracy ploys. We have a strong need to belong and feel at home. We define the world in terms of similarities and differences, in-crowds, and foreigners. Low-status groups tend to believe their position is a direct consequence of conspiracies of other groups. They regularly attribute their lesser position to a master plan of the outgroup to keep them oppressed.

“People that feel disconnected from society or experience a lack of agency and power, therefore, tend to be particularly sensitive for conspiracy thinking.”

In that respect, it is likely that the Qanon followers and the ‘deplorables’ that voted on Trump all shared a sense of loss of control over their lives and prosperity. Conspiracy theories have therefore also been called ‘the theories of the losers’ and it is indeed the case that many conspiracy theories focus on the ‘adversaries’ that happen to be in power.

How to debunk conspiracies?

Having now established that we have existential, social, complex, historical, and biological reasons to at least consider conspiracies it is no wonder they are so difficult to deal with. In fact, we still haven’t figured out how to counter them successfully. For now, we must satisfice with understanding what doesn’t work.

A route that has been often tried and failed, is the route of confrontational counter-argumentation. This route can even be counterproductive. For the believers, it only strengthens their belief in cover-ups. They only see the conspiracy at work. To make things worse their doubt and skepticism gets widened public coverage and exposure which more likely fuels the appeal of the group even more as well as that it serves as an ego-booster for (narcissistic) members that smelled a stage and fifteen seconds of fame. The public domain is the perfect yeast for a conspiracy theory and counter-argumentation in the public debate will prove of little avail.

It, therefore, seems better to tackle the problem from within. To debate and question the proof and facts within the believers’ community, to join their platforms, and to debate on their ground. That isn’t so easy. It requires at least a minimal amount of empathy for the conspiracy believers and a genuine interest in their facts, data, and rationale.

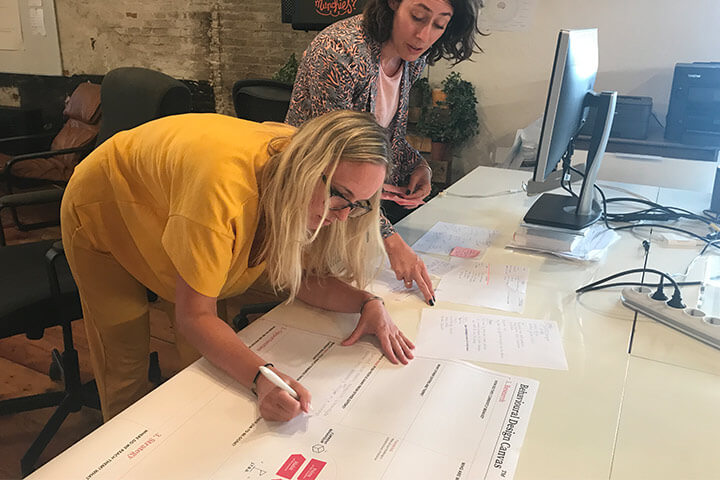

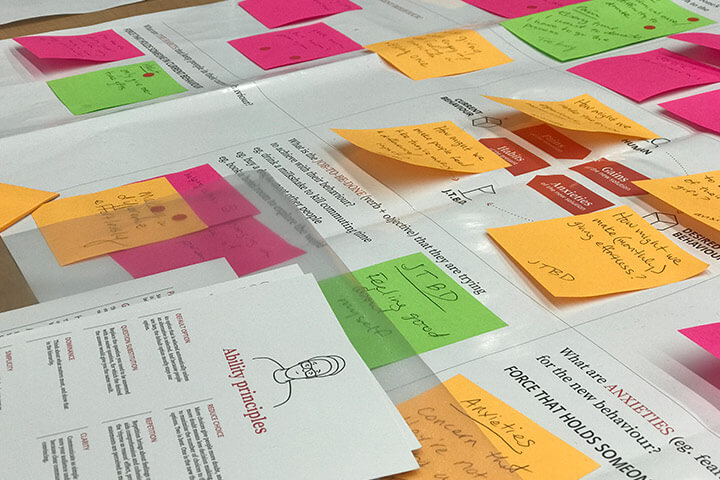

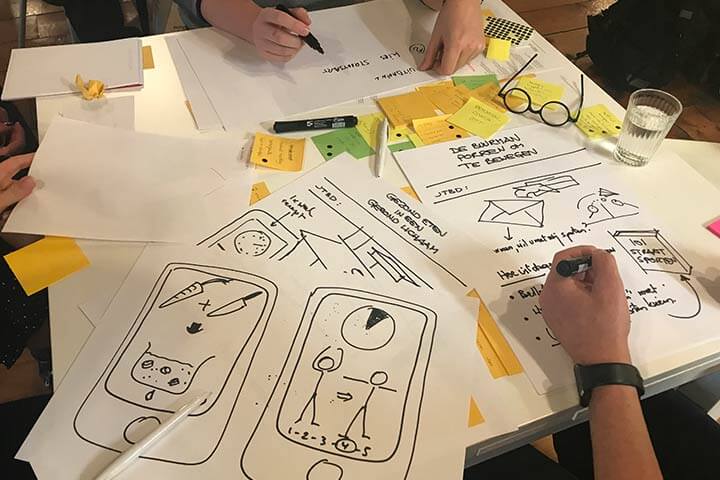

Want to learn how to apply behavioural science in practice?

Then the Fundamentals Course is perfect for you! You'll catch up on the latest behavioural science insights and will be handed tools and templates to translate these to your daily work right away. Learning by doing. We have created a brochure that explains all the ins and outs of the Fundamentals Course; feel free to download it here.

In conclusion

Clearly, it will not be a route with fast results. But in my opinion, it is one of a few feasible routes that have some chance of success. Meet them on their ground, empathize with their case and gradually probe and question their facts. You might even be surprised! Sometimes, as history has proven, … they could be right…!

As managing director of Sue Behavioural Design, it is my firm belief that solutions for the world’s challenges can’t solely come from technological innovation but need to take human psychology and social behaviors into account. With my work and writings, I hope to contribute to this view.

How do you do. Our name is SUE.

Do you want to learn more?

Suppose you want to learn more about how influence works. In that case, you might want to consider joining our Behavioural Design Academy, our officially accredited educational institution that already trained 2500+ people from 45+ countries in applied Behavioural Design. Or book an in-company training or one-day workshop for your team. In our top-notch training, we teach the Behavioural Design Method© and the Influence Framework©. Two powerful tools to make behavioural change happen in practice.

You can also hire SUE to help you to bring an innovative perspective on your product, service, policy or marketing. In a Behavioural Design Sprint, we help you shape choice and desired behaviours using a mix of behavioural psychology and creativity.

You can download the Behavioural Design Fundamentals Course brochure, contact us here or subscribe to our Behavioural Design Digest. This is our weekly newsletter in which we deconstruct how influence works in work, life and society.

Or maybe, you’re just curious about SUE | Behavioural Design. Here’s where you can read our backstory.