In this blogpost, I want to shine the Behavioural Design lens on economic thinking. I believe that how governments deal with the crisis has got everything to do with Behavioural Design.

The choices they make all have one intended goal: To positively influence the behaviour of the players in the economic ecosystem: citizen, entrepreneurs, investors, etc. Their interventions matter a lot because if they are based on wrong thinking about how incentives shape behaviour, they will result in worsening the crisis.

The economy is the sum of our beliefs of what it is

The health of an economy is nothing more or less than the collective believe we have about the future. If we are collectively convinced that things will go wrong, we will together cause the economy to contract. If you use this frame to look at the behaviour of the players in the marketplace, then the first thing you’ll notice is that the stock markets seem to be drunk with optimism again. Investors bet massively on a belief in a sharp recovery.

However, I’m not sure if we can use this signal for the real economy. Financial markets and the real economy don’t seem to have much in common these days. The stock exchange reflects more a collective belief in which companies will dominate markets in the future, and these dominating firm don’t correlate well with employment, prosperity and tax-income for the countries that host them.

‘Austerity is the dumbest idea ever.’

In the past, I have written about the Scottish Political Economy professor Mark Blyth, the author of the book ‘Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea’ (and the man behind the picture above). This lecture was the first lecture that made me understand fiscal policy-design and macro-economics (bonus: he’s a great speaker).

He makes the case that austerity is the dumbest idea ever. An idea that is gaining new momentum now since economy professor Stephanie Kelton published The Deficit Myth . The central idea that both economists propagate is that countries are not households. Countries can print money and can profit from negative interest rates, which means they get paid for lending. In other words: Countries that spend during crises, recover much faster. I wrote about this before in the blog “When accounts rule the country: On irrationality and politics“.

If this is true, then we can be hopeful that we can rebound soon, given the fact that the EU, as well as national governments, are pumping nearly unlimited amounts of capital into the economy. The question remains if this money eventually trickles down to citizens, employees, and SME’s, or if they end up filling the unlimited pockets of multinationals, and their investors. If you have inspiring sources on this topic, please share them with me.

The stimulus package debate, as seen through the lens of behavioural design

Why am I writing a newsletter on economic thinking? Because I think the choices governments are making to save the economy have every to do with behavioural design and behavioural economics.

Here’s why:

- First of all, a lot of the debates around fiscal policy seem to be completely irrational, something I have written about in the past. The fact that the Nordic countries keep insisting that the southern European countries need to feel the pain for their sinful spending behaviour in the past hasn’t got anything to do with solid economic thinking, but everything with moralism.

- When you read Mark Blyth, a thriving economy is an economy where people have money to spend. A contracting economy follows from people who are afraid to spend. European Countries so far have been doing a great job to make sure that people can keep on spending. They seem to have learned the lesson from the financial crash of 2008. This is possibly an excellent indicator for a fast rebound. He summarizes this argument very eloquently in this 5-minute video.

- Third, every intervention in the economy is a behavioural intervention. The way governments design their funds will trigger intended and unintended behaviours. Quite often, the money is not being used by those who could benefit the most from it. Quite commonly, the money is being used by ‘smart’ investors who use cheap capital to fill the war funds of technological disrupters so they can conquer the market and kill all competition. And the reason why they love these companies is that digital companies, in the end, deliver a far higher ROI, because the cost of reproduction of digital products is near zero and they rely far less on physical labour. In other words: If the rules around the abundance of cheap capital are not designed with a greedy capitalist in mind, they will only make things worse. For more on this topic: see this blog I wrote last year on The Behavioural Design of The Economy, on incentives and rewards.

I hope this gives you a new view on how to think bout these abstract concepts like Eurobonds or recovery funds. In the end, they are designed to shape the behaviour of players in the economy. If you understand how they shape behaviour, you can start thinking about the question if they are designed well or if they don’t make any sense at all.

Tom De Bruyne

You can e-mail me at [email protected], or follow my Behavioural Design Mini-courses on LinkedIn, or learn more about behavioural design on our website and blog.

Discover the missing layer of behavioural design

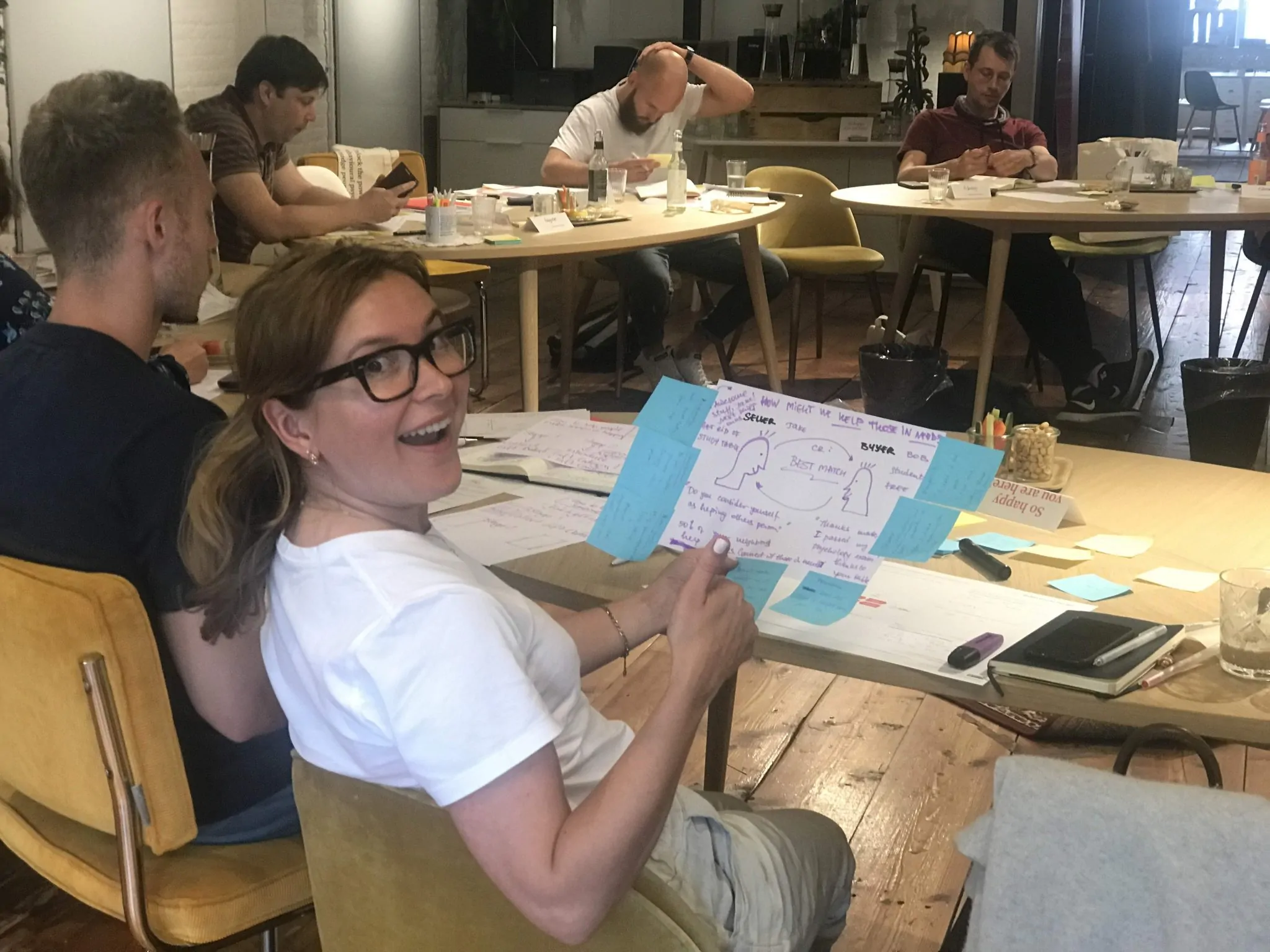

Join our Behavioural Design Academy and learn how to positively influence minds and shape behaviour

Want to learn more?

If you want to learn more about how influence works, you might want to consider our Behavioural Design Academy masterclass. Or organize an in-company program or workshop for your team. In our masterclass we teach the Behavioural Design Method, and the Influence Framework. Two powerful frames for behavioural change.

You can also hire SUE to help you to bring an innovative perspective or your product, service or marketing in a Behavioural Design Sprint. You can download the brochure here, or subscribe to Behavioural Design Digest at the bottom of this page. This is our weekly newsletter in which we deconstruct how influence works in work, life and society.

Or maybe, you’re just curious about SUE | Behavioural Design. Here’s where you can read our backstory.