The great philosopher Bertrand Russell once said “The trouble with the world is that the stupid are cocksure and the intelligent are full of doubt”. In work, life and politics there’s an overwhelming amount of bullshit being sold as knowhow. Here are 7 behavioural design rules to smell, attack and destroy bullshit

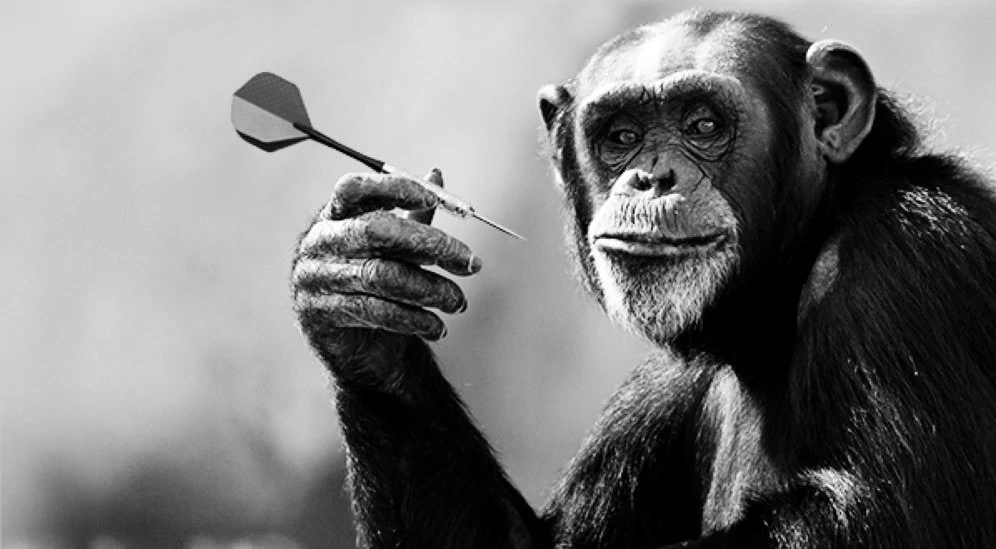

In the famous book “Superforecasting“, Philip Tetlock tells the story of how experts are on average not better than dart-throwing chimpanzees when it comes to predicting the future. Even worse, Tetlock discovered an inverse relationship between the fame of an expert and the accuracy of their prediction. In other words, TV-Pundits performed even worse than dart-throwing monkeys. The simple explanation for this remarkable feat is that pundits have this single big idea, mental model, or ideology in their head that they use as a template for everything.

If you believe passionately in free-market capitalism, then all of your predictions will be formed through this template. What Tetlock also discovered was that society greatly rewards lousy forecasters who have strong convictions than cautious forecasters, who express themselves in probabilities. People with strong opinions just make better TV. I guess this explains why total nitwits who deny the imminent threat posed by the climate crisis, always seem to outplay the more cautious scientists who are 100% sure about the size of the danger, but ever careful on how it will play out, and in which time frame. There simply is no way to predict the precise behaviours of the rapid changes in an incredibly complex ecosystem as our planet.

People with strong opinions just make better TV.

Bullshit is everywhere and on an epic scale. In this blog, I want to share some convenient rules of thumb from behavioural design to help you to smell and fight bullshit and form better judgement yourself.

Rule 1: Don’t mistake outcomes for good judgement

Never suspect a direct relationship between outcomes and the quality of the decision, unless an A/B test can prove it.

The British government under Margeret Thatcher once launched a zero-tolerance policy to fight youth criminality. No matter how small the crime, kids would end up in jail. The problem, of course, is that there’s no way to prove it worked. If crime rates went down, it could have been attributed to dozens of other factors. It’s like the story of the man who sees a guy carefully throwing powder on the side of the street. When asked what he’s doing, the guy says “this will keep away elephants”. “But there are no elephants here”, the man answers in astonishment. To which the guy replies: “Great powder, isn’t it!”.

The only condition in which you can safely say that you’re confident your action makes a difference is when you’ve done a randomised controlled test. This is an experiment in which you test one variable by assigning a random group of people to two groups. The only difference between both groups is the one variable you want to test. When Uber decided to temporarily shut down 100 million of the 150 million dollars of digital advertising spend for a week, they discovered it did absolutely nothing to their performance. They were pissing away the money, and they only found out about this after doing a proper A/B test. They eventually closed down 120 million of the 150 million dollars of their programmatic advertising budget.

“We turned off two-thirds of our spend. We turned off $100 million of the annual spend out of $150 and basically saw no change in our number of rider app installs. What we saw is a lot of installs we thought came through paid channels suddenly came through organic. A big flip flop there, but the total number didn’t change.”

Rule 2: Never confuse reasonable with rational

Confidence and arguments that sound reasonable, are how experts get away with bullshit.

As I wrote in an earlier blog, we tend to mistake confidence for competence. This mechanism is a classic ‘system 1’-shortcut. Our brain doesn’t want to waste too much energy on actively analysing a problem rationally, so it tries to answer a question by using shortcuts. The confidence of the bullshitter is a handy shortcut that allows you to make up your mind without having to think. Unconsciously, your brain thinks in a split second: “He looks like an expert” + “He seems confident about his stance” + “they allow him to say this on TV, so there must be some importance in what he says” + “He must have some information that I don’t have” = He must be right.

This reminds me about one of my all-time favourite movies “Wag The Dog“, a secret service spin-doctor Conny (played by Robert The Niro), has a memorable conversation with movie director Stanley (played by Dustin Hoffman). They both successfully staged war between the US and Albania, just to divert the public attention from the fact that the president had sex with a cheerleader, just days before the election.

Stanley: “There is no war”

Conny: : “Of course, there’s a war. I’m watching it on Television“.

The solution to this rule:

Always ask for second opinions on important decisions. It’s not because an expert sounds confident that you should take his word for granted. Even the emperor is naked underneath their clothes. Furthermore, never give the information you got from your first source to the second source, because this will unconsciously influence their judgement.

Rule 3: Attack vagueness

Never let people get away with vague predictions because they can never be held accountable.

If a pundit says: “This decision by the European Union will very likely push the economy into a recession”, and after a year this prediction hasn’t materialised, they can always get away with “oh, just wait. It hasn’t happened yet” or, “I said very likely. That didn’t imply I was sure”. Vague predictions are compelling: They sound reasonable, and they always allow you to get away with things.

In the Ancient Greek City of Delphi, people went to see the high priest called Pythia, to ask for predictions. High as a kite, she murmured some incomprehensible sounds, that were interpreted by her nodding assistance, who seemed to indicate that they understood what she was saying. They translated the outcome in verses, so they could always be assured that there was still lot’s of room left for multiple interpretations.

The Solution to this rule:

Most pundits are really good at using the same techniques that the Pythia priestesses used in the 8th century BC. You can freak them out if you push them to be more precise about their prediction. If they can’t, then accuse them of bullshit.

Rule 4: Always suspect confirmation bias

When you hear someone defending their judgement with research: Always look for confirmation bias

The business model of firms like McKinsey or Boston Consulting Group is to provide arguments for a decision that was already made. This is called Franklin’s Gambit – the process of creating or finding a reason for what one already has a mind to do. 18th-century inventor Benjamin Franklin first stipulated this principle. Kahneman would call this principle the confirmation bias: the tendency to look only for evidence that supports one’s convictions.

The irony of Franklin’s gambit is that it’s probably nowhere as persistent as in a discipline that always insists on projecting an image of ultimate rationality: the financial sector. In the years leading up to the 2008 crisis, report after report was commissioned and published that underscored how genius the so-called mathematical models were and how incredibly successful the financial sector was in creating value and wealth.

Counterfactual evidence was being ignored with force: Whistelblowers were bullied; credit rating agencies blackmailed (or participated in the scam); the financial press had all kinds of perverse incentives not to spoil the party because that could hurt the stock market. Etcetera.

The solution to this rule:

There are some fascinating experiments with blue teams vs red teams. Some investment firms assign a red team that will get a big incentive if they can bring up the arguments to kill the deal that the company is working on. This setup prevents the firm from being too blinded by the prospect of success.

A more straightforward approach: always look for counterfactual data and learn a great deal by how the other party responds to this data. If they use it to improve their argument, you will get a better hunch about whether they know what they’re talking about.

Discover the missing layer of behavioural design

Join our Behavioural Design Academy and learn how to positively influence minds and shape behaviour

Rule 4: Always look for Skin in the Game

Always check how much skin in the game the other has.

I have written about this topic before in this blog so that I can be brief here: If someone is trying to persuade you to buy something from him or her, always try to get a feeling if he or she can both win and lose. The one simple intervention that could take away most of the excessive risk-taking in the financial sector is to introduce punishments next to bonuses. If I would offer you a chance to win big if you win, but lose nothing if you lose (because you’re playing with my money), wouldn’t you be tempted to play as much, and as risky as you can? That’s the financial crisis of 2008 in a nutshell in behavioural terms.

The one simple intervention that could take away most of the excessive risk-taking in the financial sector is to introduce punishments next to bonuses.

Like Warren Buffett once said: If you sit at a poker table and you don’t know who’s the patsy: you are the patsy.

The Solution ot this rule:

Never buy or trust people who have nothing to lose and much to win, whether that’s money or a good reputation.

Rule 6: Expect Goodhart’s Law at work

Goodhart’s law: never trust metrics that are KPI’s

Have you ever heard about the Net Promotor Score? The magical, simple metric that predicts future success, based on how likely customers are to recommend the product or business to their friends. To measure NPS, you ask the one question: How likely are you to recommend this product/service and people have to rate their satisfaction from 1 to 10.

This metric is highly problematic for several reasons:

- First of all: My 5/10 could mean the same thing as your 7/10. Attaching a number to a subjective feeling is very personal.

- Second: You have to measure the NPS by the percentage of promotors (the percentage of customers who gave you a 9/10 or 10/10) minus the percentage of detractors (the percentage of customers who scored you under 7/10 is). If you have 0 people rating you with a 9 or 10, and 10 people rate you with a 7/10, your NPS will be -100. If you have two people rating you with a 9/10, but 8 people gave you an angry 0/10, you will end up with an NPS of -60. In other words: You won’t see how dramatic you’re doing, because you’re NPS goes up.

- Third: Therefore, it’s quite apparent how much incentives there are to influence the NPS. When your bonus depends on improved NPS-ratings, there’s so much you can do to manipulate the numbers: Avoid asking the question to angry customers, give happy customers extra nudges to fill in the questionnaire. Present the question at a peak moment in the customer journey. Etc.

This phenomenon is called Goodhart’s law, and it says: every metric that is used as a KPI, loses its value as a metric. If you give targets to police officers, they will get highly incentivised to harass people, just to meet their goals. If you connect funding of Universities to performance thinking, universities will become incentivised to attract as many students as possible, shut down departments with fewer students and skew investments only towards hard sciences. If you introduce individual bonuses, people will be very incentivised to meet their bonus at all costs, even if this would imply getting into a fierce competition for resources with other departments.

When a KPI is introduced, it will start to direct the behaviour of the people affected by that KPI.

The Solution to this rule:

Whenever you’re involved with planning and goal setting: Always look for perverse incentives. They’re everywhere. And they’re nearly always neglected or thought of as trivial. The problem with KPI-setting is that it’s the people who pretend to be rational, who do the thinking. They usually think of human behaviour as nothing more than a nuisance to their spreadsheets.

Rule 7: Status Anxiety affects Judgement

Never underestimate status anxiety as a driving force of bad decision making

In his magnificent book Alchemy, Rory Sutherland asks his reader to imagine the following story: Suppose you have to book a flight to New York for your boss. You know JFK is a nightmare: Long cues, lot’s of delays, endless transfer walks and when you finally leave the airport, you’re rewarded with a traffic hell till Manhattan. So you decide to do something slightly less obvious: You book a ticket to Newark, New Jersey: This is a much smaller airport, you can see the Manhattan skyline from the airport and traffic is pretty OK. The thing is: you have now taken a risk by trying something new, against the obvious popular choice. If it goes right, your boss will hardly notice. But if something goes wrong, like a flight delay, you will be blamed for stupid decision-making. “What were you thinking!” “There’s a reason why everyone flies JFK!”.

Rory Sutherland has this brilliant quote:

“It is much easier to be fired for being illogical than it is for being unimaginative. The fatal issue is that logic always gets you to the same place as your competitors.”

The problem with being imaginative is that it usually defies ‘common practice’ or ‘common sense’. And doing something different can trigger all kinds of unwanted consequences: You can be held accountable for taking a decision that didn’t work out. If you would have followed standard practice, nobody will blame you. You can also be blamed for not respecting authority. I have written before about how the nuclear disaster in Chernobyl can be read as a story of layers upon layers of bosses that were highly incentivised not to hear bad news. So they didn’t get to hear bad news. The reactor was so unstable that it took nerve-racking skills from the operators to keep it afloat. One fatal mistake triggered a cascade of nuclear reactions that caused the nuclear meltdown.

The Solution to this rule:

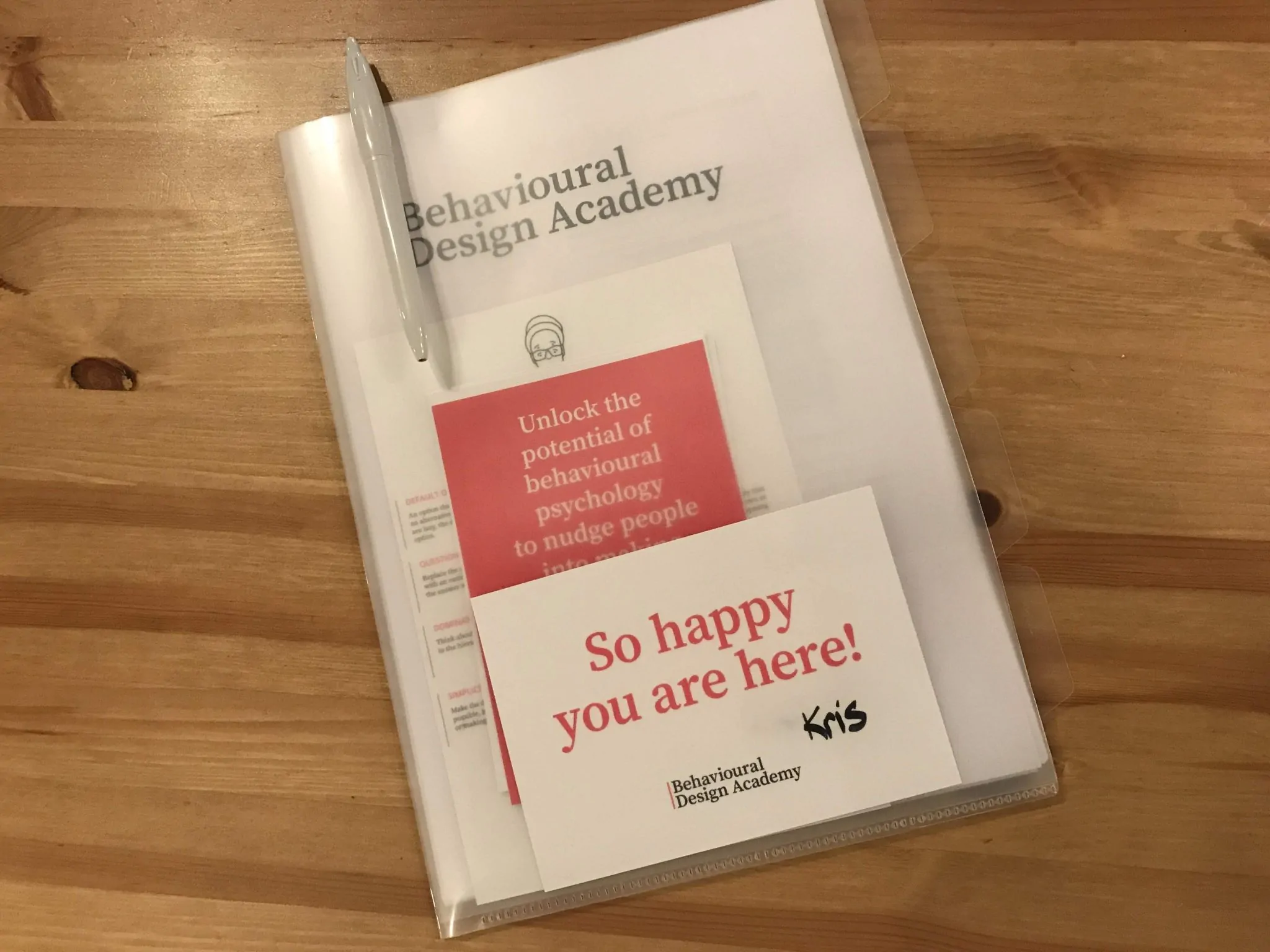

Always try to understand the forces that shape the behaviour of the other. Use the Influence Framework to map their pains, gains, habits and anxieties and Jobs-to-be-done: Try to understand how they define success? What keeps them awake? What are the things they are accountable for? Whom do they have to convince in their organisation? How is their relationship with those stakeholders? Only when you understand the social web around the other, you will get a better understanding of what prevents them from bold or confident decision-making.

Also Read: The psychological prize of being rational is being unlikeable

More on Personal Development / Self-Improvement

A series on blogposts on how to apply behavioural design thinking to design a better life.

- Prototyping happiness (on the power of prototyping to increase your happiness).

- How can you trust an expert? (a post on the concept of Skin in the Game)

- The dark design patterns that made me quit Twitter

- The behavioural design of love and desire (how to have a fulfilling love and sex life)

- How to make New Years’ resolutions that stick ?

- Personal Coaching is pointless (why team coaching is much more interesting)

- How to live a meaningful life in a world that is spinning out of control?

- How to lose weight using Behavioural Design? (Never trust a behavioural Designer who’s out of shape)

How does influence work in practice?

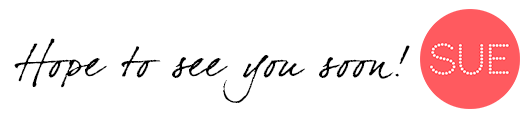

Enroll now in one of our monthly editions of the Behavioural Design Academy. and learn how to predictably change behaviour. SUE trained over 1000 people from 40+ countries and our program is rewarded with a 9,2 satisfaction rate.

Want to learn more?

If you want to learn more about how influence works, you might want to consider our Behavioural Design Academy masterclass. Or organize an in-company program or workshop for your team. In our masterclass we teach the Behavioural Design Method, and the Influence Framework. Two powerful frames for behavioural change.

You can also hire SUE to help you to bring an innovative perspective or your product, service or marketing in a Behavioural Design Sprint. You can download the brochure here, or subscribe to Behavioural Design Digest at the bottom of this page. This is our weekly newsletter in which we deconstruct how influence works in work, life and society.

Or maybe, you’re just curious about SUE | Behavioural Design. Here’s where you can read our backstory.