The ethics of Behavioural Design

The ethics of Behavioural Design

This post is a long-read about a subject that is very close to our hearts: the ethics of Behavioural Design. It will shed a light unto how we incorporate ethics in our way of working. It will also provide you with practical tools to help you pinpoint the considerations you need to make to safeguard the ethics in Behavioural Design. It is our take on things. It isn’t perfect yet. It is ever-evolving work-in-progress, but it is a solid start. I would love for you to read the whole post, but you can also jumpstart to specific parts right way:

- Manipulation or positive influence?

- Behavioural Design ethics: The Organisation Level

- Behavioural Design ethics: The Personal and Team Level

- Behavioural Design ethics: The Project Level

- How Behavioural Design ethics make both human and business sense

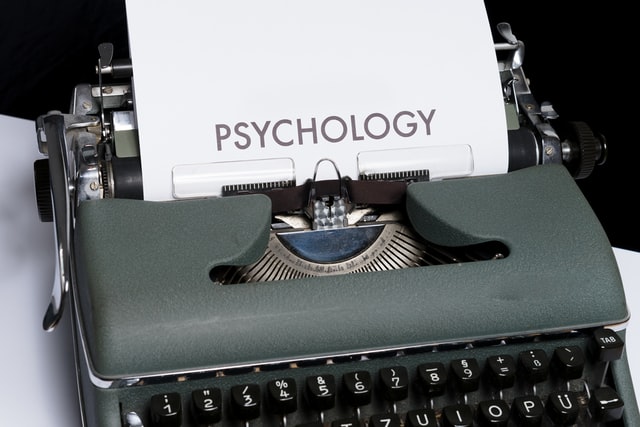

Manipulation or positive influence?

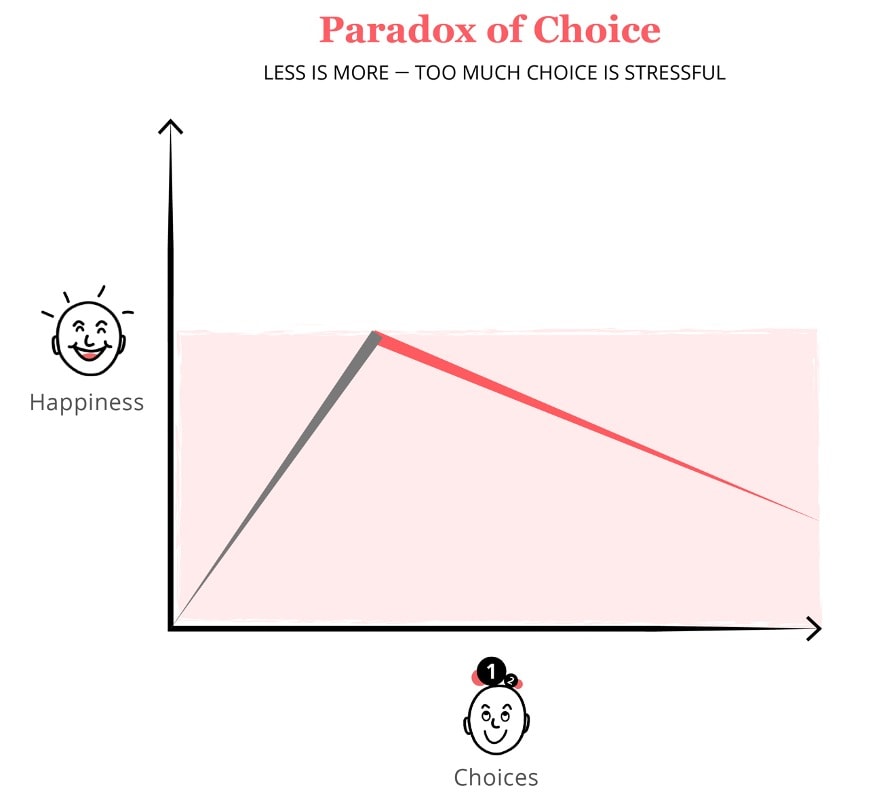

When engaging in Behavioural Design, there is one critical question to ask ourselves: Are we in the manipulation business or are we designing positive influence? It is vital to address the ethics of Behavioural Design. Know-how of behavioural science can be a potent tool to influence choices and shape decisions. It can be a very dark art. It can, for example, be (and is) used to get people hooked to phones or unhealthy foods, to manipulate voting behaviours or create division in society. It can be used to exploit peoples’ fears and anxieties.

However, it can also be applied to help people engage in healthier habits such as exercising or eating healthy food or to create a better world by for example helping people to recycle, to act against climate change or to help others in need. Therefore, behavioural science in itself isn’t dark art as such; it is what you do with it. It is all comes down to intention.

However, it can also be applied to help people engage in healthier habits such as exercising or eating healthy food or to create a better world by for example helping people to recycle, to act against climate change or to help people in need. Therefore, behavioural science in itself isn’t dark wisdom as such; it is what you do with it. It is all comes down to intention.

If your intention is not the progress or the improvement of the person(s) you are trying to influence, then you are manipulating. If your intention is to help people make better decisions that will improve their life, work or living environment, that’s positive influence.

At SUE | Behavioural Design, we are very much concerned about the ethics of applied behavioural science. Our mission is to unlock the power of behavioural psychology to help people make better decisions in work, life and play. As we are in the business of designing interventions that will influence choice and shape behaviour, we need to have a clear vision of the ethics of Behavioural Design and code of conduct. As mentioned earlier, the know-how of how people make decisions and how behaviour is shaped can be very dark art. Unfortunately, the people who are now really using behavioural science at scale often don’t have good intentions. And that, to us, is manipulation. It is meant for personal advancement or meant to benefit a privileged few.

That’s why we at SUE are on a crusade to introduce more people to the know-how of behavioural science and provide them with the practical tools to use it in their daily lifes.

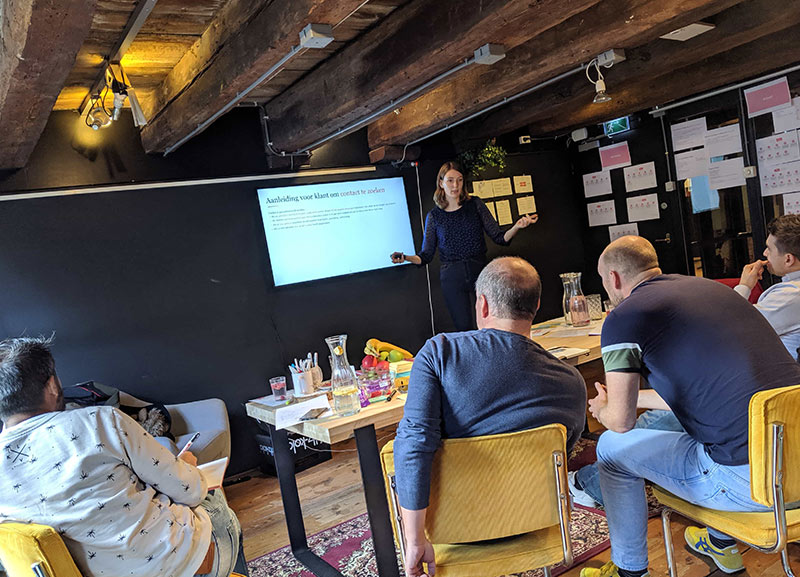

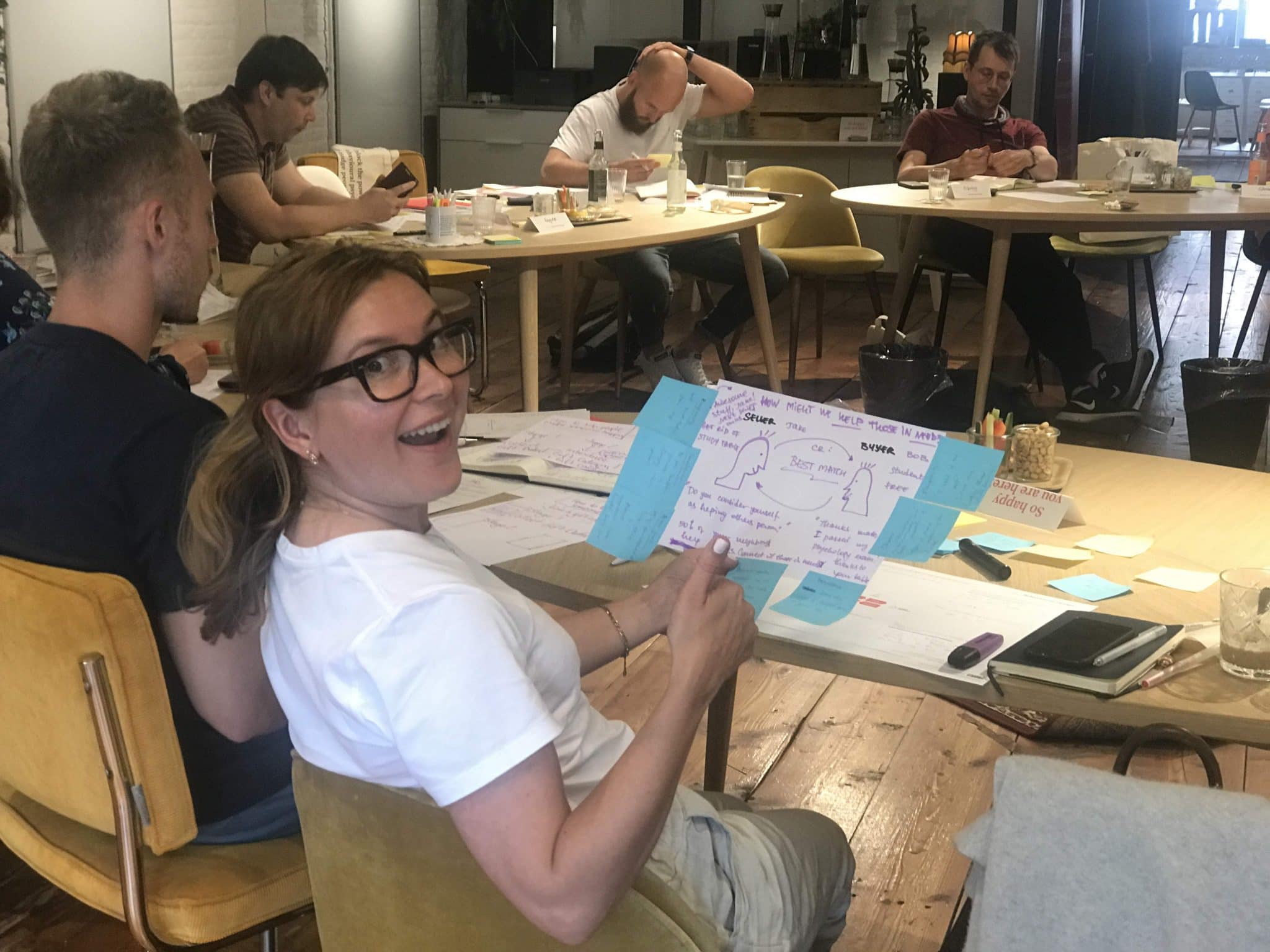

So, people can genuinely apply Behavioural Design to improve their own lives, that of others and the planet we live on. This is the reason for the founding of our SUE | Behavioural Design Academy© and writing a book on Behavioural Design that will be published next spring: To give more people the tools to use Behavioural Design for good.

So, our company mission implies that we should walk the talk. We simply have to have a clear vision of the ethics of Behavioural Design and we have to abide by that vision in practice. Unfortunately, there isn’t already a commonly accepted code of conduct in the behavioural science field. However, there are some interesting resources out there of organisations and people who want to use this powerful know-how for good. In this article, we want to provide you with insights and tools that we use as our ethical compass. Which can be applied on three levels:

- The Organisational level

- The Personal and Team level

- The Project level

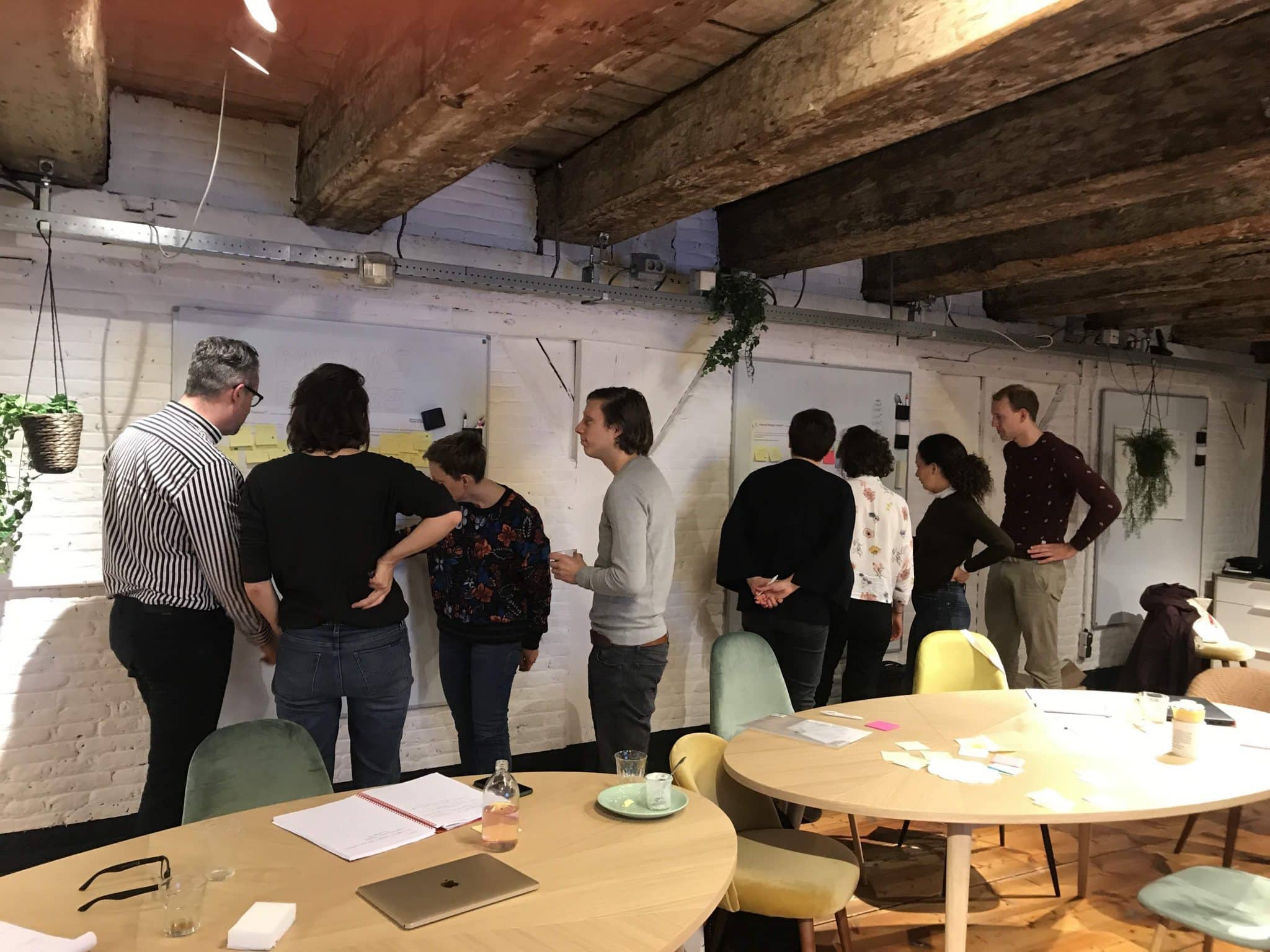

We hope it will give you some practical guidelines on how to use Behavioural Design for positive influence. It isn’t perfect yet. We are prototyping and learning every day. It is constant work in progress that we will keep sharing with you. Our goal is to be very open and transparent about how we try to safeguard the ethics of Behavioural Design and how sometimes we struggle with it. We hope you in this for the sake of progress, improvement, better decision-making and positive behaviour, and you will embrace our tools and best practices. Let’s create a positive countermovement by together applying Behavioural Design for good. Counterbalancing and exposing those who use it with evil or selfish intentions.

Behavioural Design ethics: Organisation Level

Mission and company culture

At an organisation level, it all starts with having an actionable mission that has progress in its DNA and is backed up by the willingness and capability within the organisation to act upon it. This requires a mandate from management but also a company culture that attracts talent and clients who fit and believe in this mission and that rejects those who don’t. It also requires a company culture that is open to discussions. Our mission is:

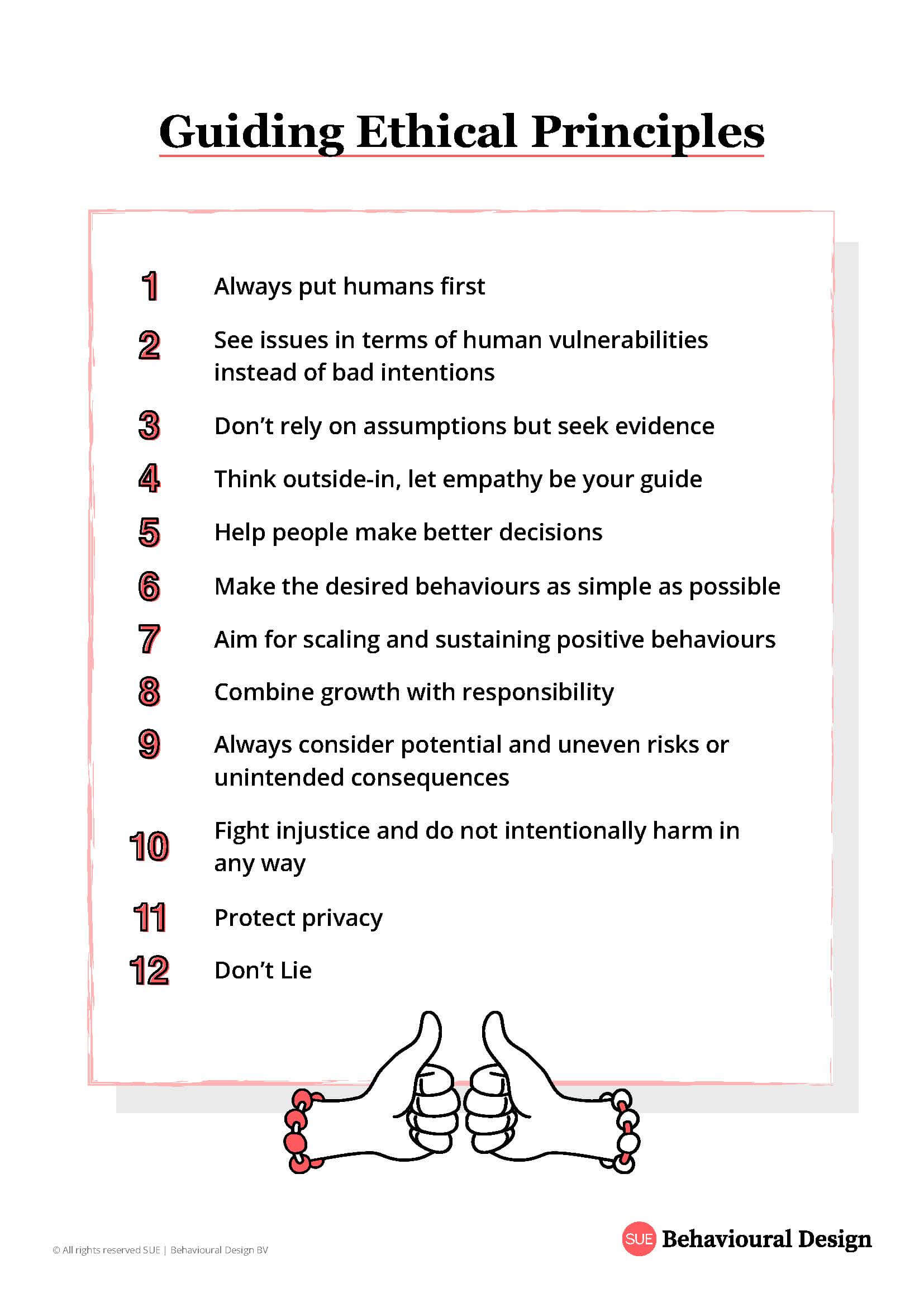

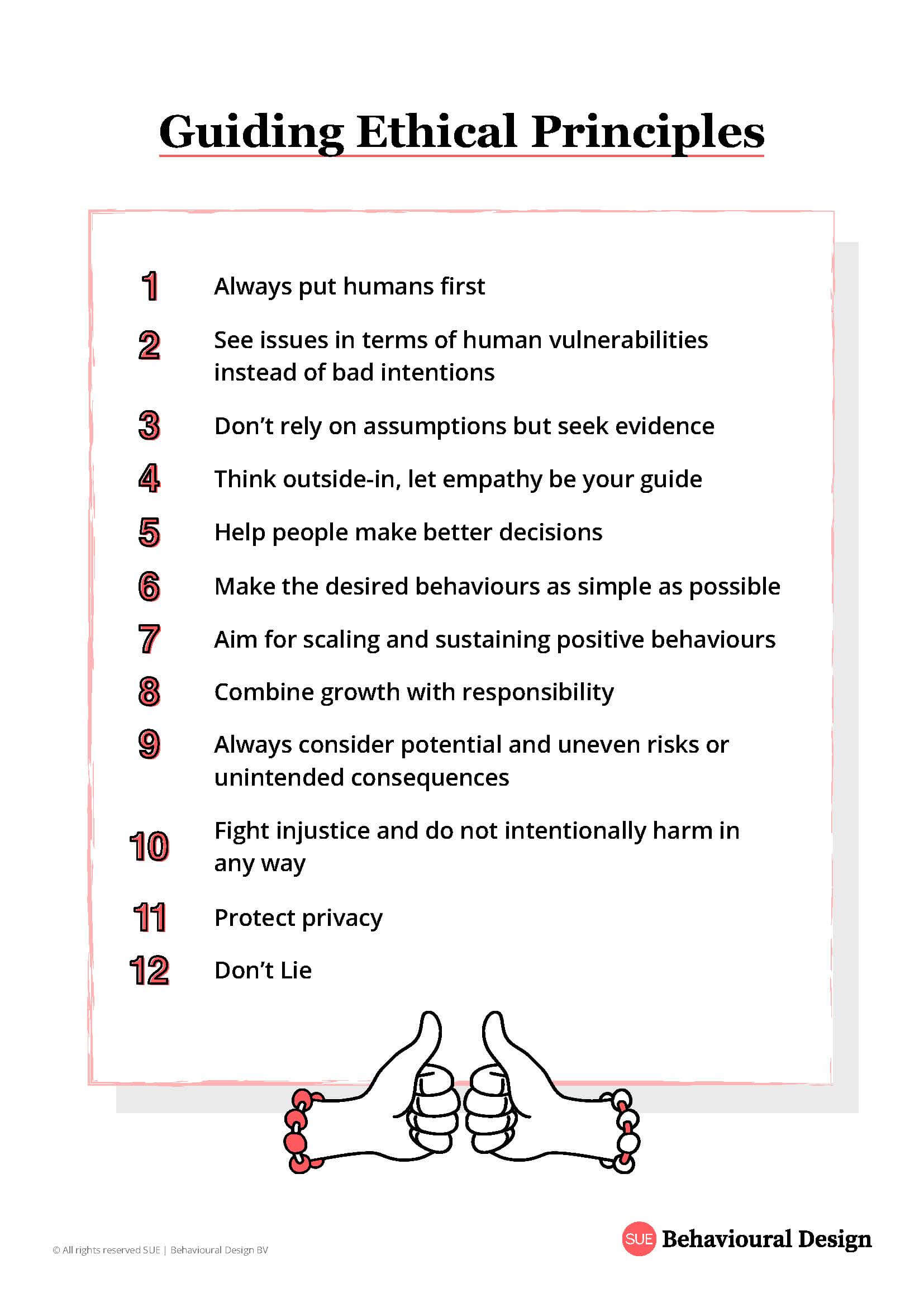

We live by our Behavioural Ethics Principles, which are:

Selection of clients and projects

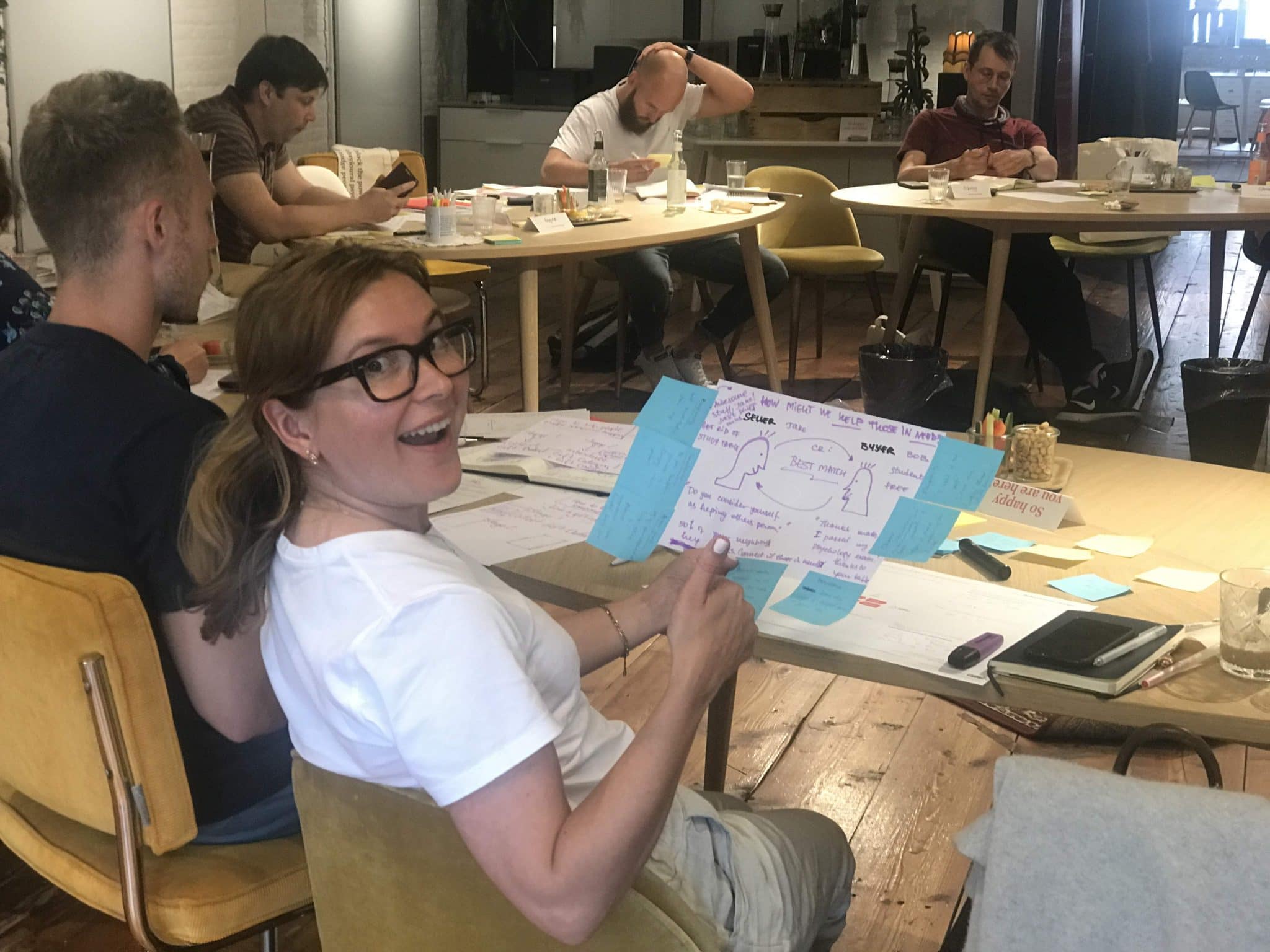

Next to the mission and principles, we also safeguard our Behavioural Design ethics by carefully selecting the projects we engage in and the people with whom we work. Both at SUE and our Academy, we aren’t one-size-fits-all. Even in the days when we still were a small-scale company with not much money in the bank, we decided always to put our mission first and be selective in who we work for and who can enrol in our training.

We will never work for or train people working in industries that harm people, animals, the planet or neglect social and equality rights (if you want to find out more check out our Terms & Conditions). We will not sell our souls to the devil, not for a million. Or more. However, sometimes the world isn’t as black and white, and we find ourselves in shades of grey. This sometimes results in difficult decisions. Decisions which we always genuinely try to make based on our moral compass, and which are still open to discussion for anyone within our company.

Ongoing discussions

That being said: We do have ongoing conversations in our team about projects we work on. Not working for the fur, tobacco or weapon industry is an easy decision to make. But should you work for an alcoholic beer brand or only for their 0% beers? Or milk? Or the oil industry, if they want you to work on their transition to sustainable energy? There aren’t always clear-cut answers to this and they alway s lead to different points-of-view. This is one way we try to safeguard our ethics: by actively and purposefully keeping the ethical discussion alive in our team. This code of ethics you are reading right now and the tools that come with it help us define the boundaries. Sometimes boundaries change because we learn.

And there are, of course, always loopholes. We had someone who ‘slipped’ into our Academy by applying via a Gmail address and faking his employer details. And we failed to do a sufficient background check. He turned out to work for a cigarette brand. That was not one of our finest moments, and our background checks are far more thorough now – trust me. But we don’t have and will never have a complete sense of control over who reads our blogs, sees our Keynotes, uses our tools, watches our videos or will buy our books. We know this, and we are aware of it.

A positive perspective on human nature

We just don’t want to live our lives with a negative perspective on human nature. We hope everything we do at SUE | Behavioural Design and the SUE | Behavioural Design Academy© will spread massively, and we genuinely believe the intentions of the majority of people are not bad. We refuse to believe that. We as people are just sometimes clumsy, too emotional or merely incapable. If you look at people as humans who are trying their best, they can sometimes fail because of the context they find themselves in. Heavily influenced by biases, past experiences and short-cuts, this lowers your pessimism about human nature. Try judging people through the lens of ‘good people, bad circumstances’[1], and I assure you it will take the edge of your annoyances and will foster empathy and a belief that the majority of people mean well.

We as SUE want to give more tools to these masses to help them make better decisions. Will we also reach the 2% asshole population? Maybe. If you recognise yourself as being an asshole, go away now. Our services and tools aren’t meant for you. Black-out what we have written, burn our writings, shred our tools. We don’t care, whatever makes your black heart tick. But leave. Now.

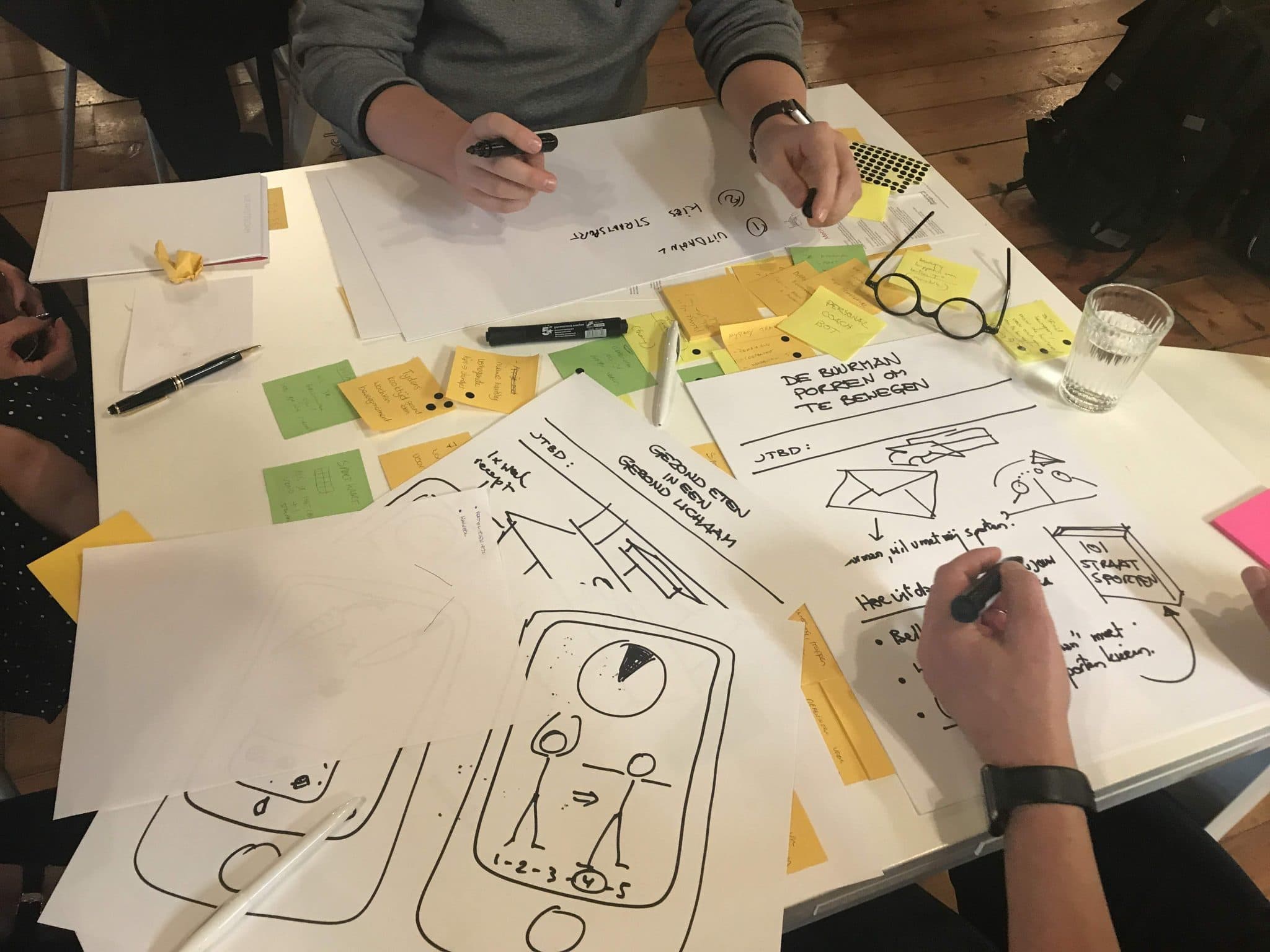

SUE | Influence Framework©

But it’s not just the way you look at things; it is also the way you act. As said, whether Behavioural Design is a pearl of dark or enlightened wisdom all starts at intent. Is your intention to do harm or good? Is it about shareholder value alone? Or are you genuinely trying to add human value? (which can also make you good money by the way) We have developed the SUE | Influence Framework©, a powerful tool to understand human decision-making and the forces that drive or block behaviour. It helps to turn human insights into tangible interventions that will spark positive action. It is a systematic approach to think outside-in instead of inside-out. It will put humans first and not yourself.

The framework in itself is all about progress:

- Can we resolve pains?

- Can we enlarge gains?

- Can we take away anxieties?

- Can we create better comforts?

- Can we make sure we can help people achieve their jobs-to-be-done in a better way?

We would love for every organisation to start using the SUE | Influence Framework© (we can help you apply it in a Behavioural Design Sprint or teach you how to use it yourself in our Academy). Still, the more important point we want to make here is that embedding a workable method in your organisation that genuinely puts humans first, is key to designing for good. Of course, the SUE | Influence Framework© is the best way to do this but on a more serious note: it helps us and the clients we work for to grasp human decision-making.

The SUE | Influence Framework© reveals that often people have the best intentions, but stumble upon behavioural barriers and bottlenecks that prevent them from doing the better or right thing.

So apart from the framework helping you to become radically human-centred and discovering the human behind your client, employee, citizen or whomever you are trying to influence, it also is a revelation as it shows that having a positive perspective on human nature is indeed not just touchy-feely but a a methodical process.

Design for large scale impact

What is a work in progress to us, is making the shift from more individualistic (or small group) behavioural interventions to influencing collective behaviour.

To have a genuinely positive impact, you need to reach a certain point of adoption. Coming up with system interventions and creating network effects is a way we can design for good on a larger scale.

One way we are working on this is that we are adding quantitative research to our SUE | Behavioural Design Method© to substantiate our behavioural insights and find evidence for the weight of the behaviour drivers of a problem. Another way is that we are looking to run pilot projects after our prototyping tests to discover that we can scale the behavioural interventions and test their positive impact on a larger scale. We believe future lies in connecting behavioural science with network science and systems thinking. We haven’t gotten all our ducks in a row just yet, but we are working on this.

There is a cognitive bias related to this phenomenon called

There is a cognitive bias related to this phenomenon called

Suppose you want to learn more about how influence works. In that case, you might want to consider joining our

Suppose you want to learn more about how influence works. In that case, you might want to consider joining our

How to convince someone with different beliefs

How to convince someone with different beliefs

Bypassing confirmation bias (2): Provide proof not evidence

Bypassing confirmation bias (2): Provide proof not evidence

We felt we were on the right track with the ‘bin issue’. By discussing this issue more deeply in brainstorms, by physically analyzing our own kitchens and by adding some common sense (where would you be without), we concluded that every kitchen has só many potential organic waste ‘bins’: a pot used during cooking, an empty little mushroom box, an empty salad bowl. In other words, simply every kitchen object where you can put organic waste in will do (I don’t recommend using a little girl’s lunchbox, my daughter didn’t appreciate it).

We felt we were on the right track with the ‘bin issue’. By discussing this issue more deeply in brainstorms, by physically analyzing our own kitchens and by adding some common sense (where would you be without), we concluded that every kitchen has só many potential organic waste ‘bins’: a pot used during cooking, an empty little mushroom box, an empty salad bowl. In other words, simply every kitchen object where you can put organic waste in will do (I don’t recommend using a little girl’s lunchbox, my daughter didn’t appreciate it).

Also, we designed a so-called ‘wheelie bin bingo’. All citizens of Amersfoort with a green wheelie bin (for organic waste) received a brochure in their postbox. This brochure contained, amongst other things, information about the importance of separating waste and tips & tricks regarding the right way to do it. But it also included a sticker upon which people had to write down their house number. By pasting their sticker on their green wheelie bin, all citizens were automatically enrolled in the periodic ‘green wheelie bingo’ (having a chance to win modest but fabulous prizes).

Also, we designed a so-called ‘wheelie bin bingo’. All citizens of Amersfoort with a green wheelie bin (for organic waste) received a brochure in their postbox. This brochure contained, amongst other things, information about the importance of separating waste and tips & tricks regarding the right way to do it. But it also included a sticker upon which people had to write down their house number. By pasting their sticker on their green wheelie bin, all citizens were automatically enrolled in the periodic ‘green wheelie bingo’ (having a chance to win modest but fabulous prizes).