In this blog, I want to explore the different forces that shape behaviour change. Whenever you want to design a strategy that aims at changing behaviour, you have to ask yourself three questions:

- Macro-forces: What are the trends I can tap into?

- Meso-forces: What are the needs I can tap into?

- Micro-forces: What are the biases I can tap into?

1. The macro forces: What are the trends I can tap into?

1. The macro forces: What are the trends I can tap into?

The world is changing at an accelerating speed. It took only 66 years between the first flight of the Wright brothers and Neil Armstrong, setting the first step on the moon in 1969. It only took 30 years for China to transform from a developing country into the biggest economy in the world. The iPhone is only 14 years old, kickstarting an era of ubiquitous access to knowledge, services, social capital and radical new ideas for commerce, creating companies like Uber, Netflix and Amazon.com. Over the past few decades, China alone has lifted hundreds of millions of citizens to become part of the middle class. And middle-class people want stability and want to consume, travel and be entertained.

These macro forces have an enormous impact on behaviour change.

If you want to introduce an innovative offering into the market, it matters a lot if you’re able to tap into these trends.

If you are Carsharing company Sharenow, it matters a lot if you can tap into a big inner-city market of people who don’t own a car and feel perfectly comfortable hiring and unlocking one with their smartphone. What seemed unfamiliar five years makes perfect sense today. We’ve seen an interesting trend in the Netherlands during COVID of families leaving the metropolitan cities and moving into the countryside or smaller communities. This trend is an exciting opportunity to tap into e-bikes and electric cars. Another emerging trend that COVID accelerates is that every entrepreneur is thinking hard about designing the optimal environment for combining physical presence with distributed working.

When you think about introducing a new product or service into the market, it’s vital to understand the trends. Successful innovators understand that demographic, technological, cultural and economic trends generate new opportunities.

2. Meso-Forces: What are the needs I can tap into?

2. Meso-Forces: What are the needs I can tap into?

The second category of forces that shape behaviour are needs and motivations. They drive behaviour in unconscious yet essential ways. All of us have deeply rooted desires: The desire for love, recognition, competence, social status, belonging, adventure, purpose, protection and excitement. Every brand in the world taps into these deeper needs:

- BMW taps into the desire to project masculinity and social status

- Volvo taps into the desire for security and protection

- Beer brands all tap into the desire for friendship and connection

- Business schools tap into the desire for competence and social status.

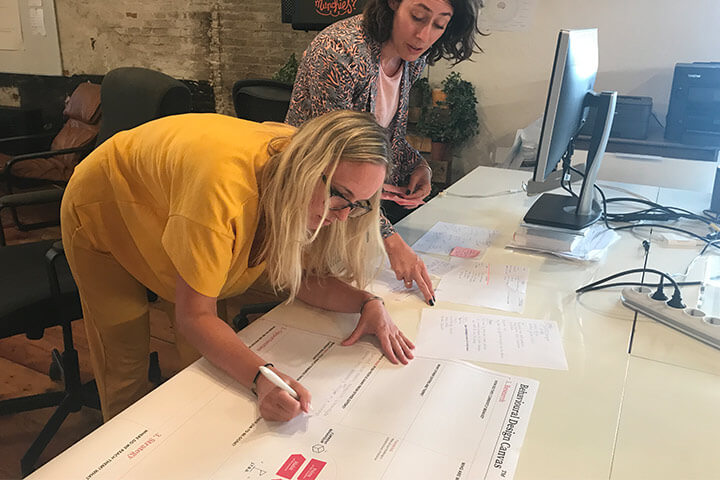

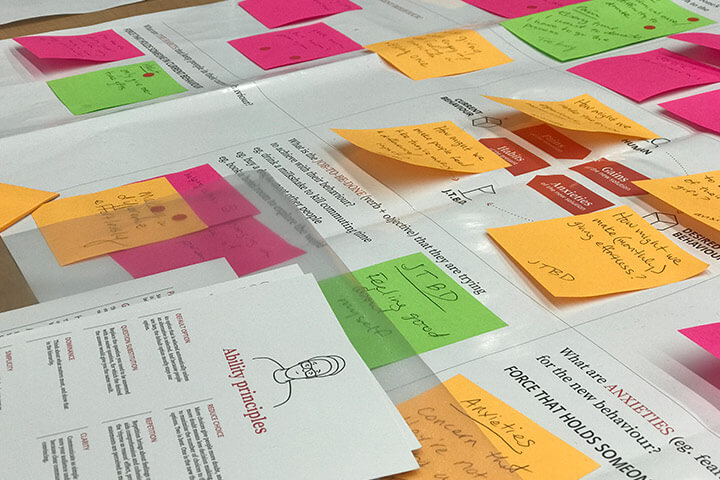

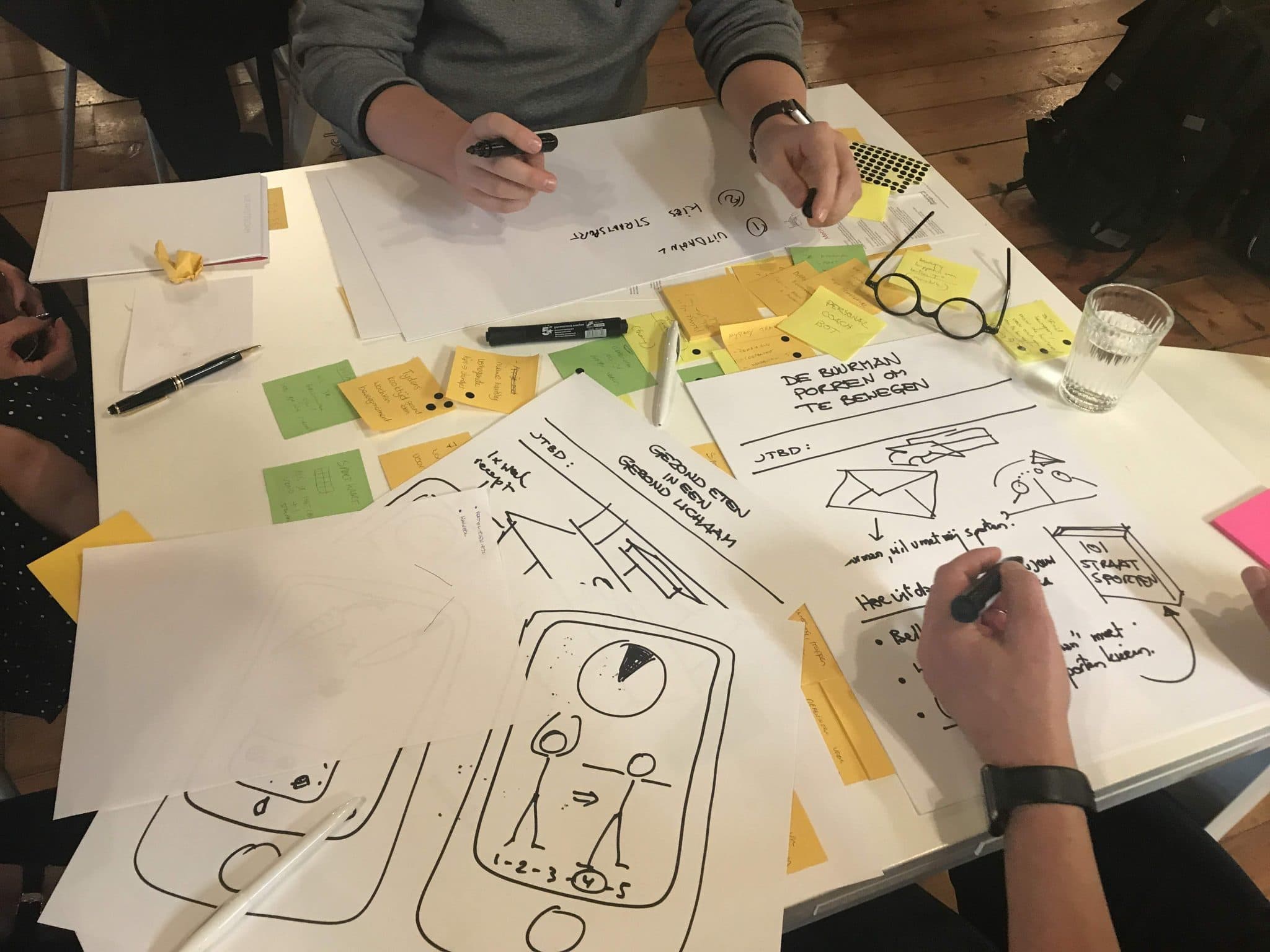

There’s a saying in Silicon valley that every successful tech company taps into one of the seven deadly sins. Understanding these drivers, motivations or Jobs-to-be-Done is essential for designing interventions for behavioural change. If you can’t tap into an existing desire, your intervention will probably fail. The Behavioural Design Canvas is a great tool to uncover these forces.

Want to shape behaviour and decisions?

Then our two-day Fundamentals Course is the perfect training for you. You will learn the latest insights from behavioural science and get easy-to-use tools and templates to apply these in practice right away!

3. Micro-Forces: What are the biases I can tap into?

3. Micro-Forces: What are the biases I can tap into?

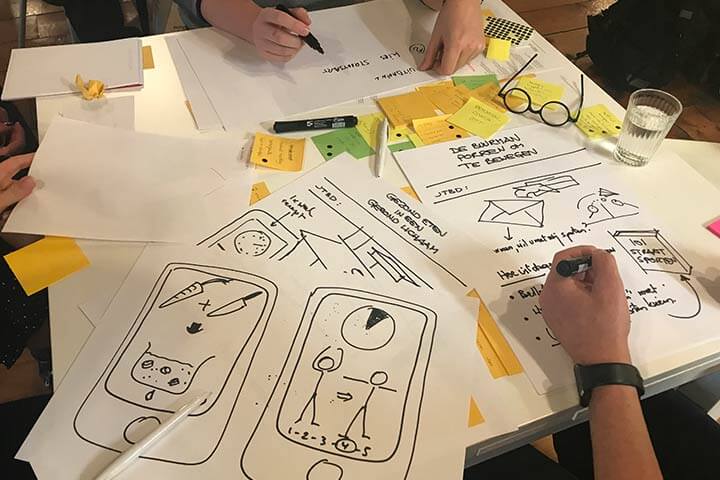

The third category of behavioural forces is micro-forces. Let’s suppose you uncovered a behavioural trend (say: middle classes flock to cities in hordes and can’t afford a car). You also crafted a proposition that taps into a deep desire (e.g. you offer luxury electric vans to go on weekend trips in the countryside to fulfil the desire for adventure and social status).

The big question from a behavioural change perspective is now: How do I trigger people to buy what I’m offering?

To become successful, you will need to find ways to get people to see the message, boost the motivation to try it, reduce doubts and uncertainties and make it as easy and frictionless as possible to order it. In the case of our electric van, you will boost motivation through social proof, reduce anxiety by demonstrating the comfort of sleeping in the vehicle in a demo video or guaranteeing 24/7 support, including insurance. You might want to look for hot trigger moments and advertise on billboards near busy roads, where traffic jams increase people’s motivation for escapism.

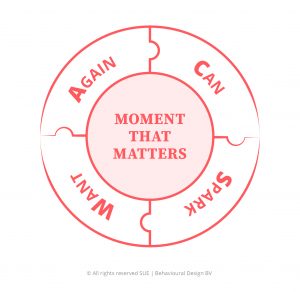

For this layer, a great tool to think about designing interventions is our SWAC-tool. In the SWAC-model you will find many principles from the science of influence to spark behaviour (S), to boost the desire to want (W) something, to help people to be able, so they can do it (C), and make them do it again and again (A).

Summary

Cover visual by Kelly Sikkema on Unsplash.

BONUS: free ebook 'How to convince someone who believes the opposite'

Especially for you we've created a free eBook 'How to convince someone who believes the opposite'. For you to keep at hand, so you can start using the insights from this blog post whenever you want—it is a little gift from us to you.

How do you do. Our name is SUE.

Do you want to learn more?

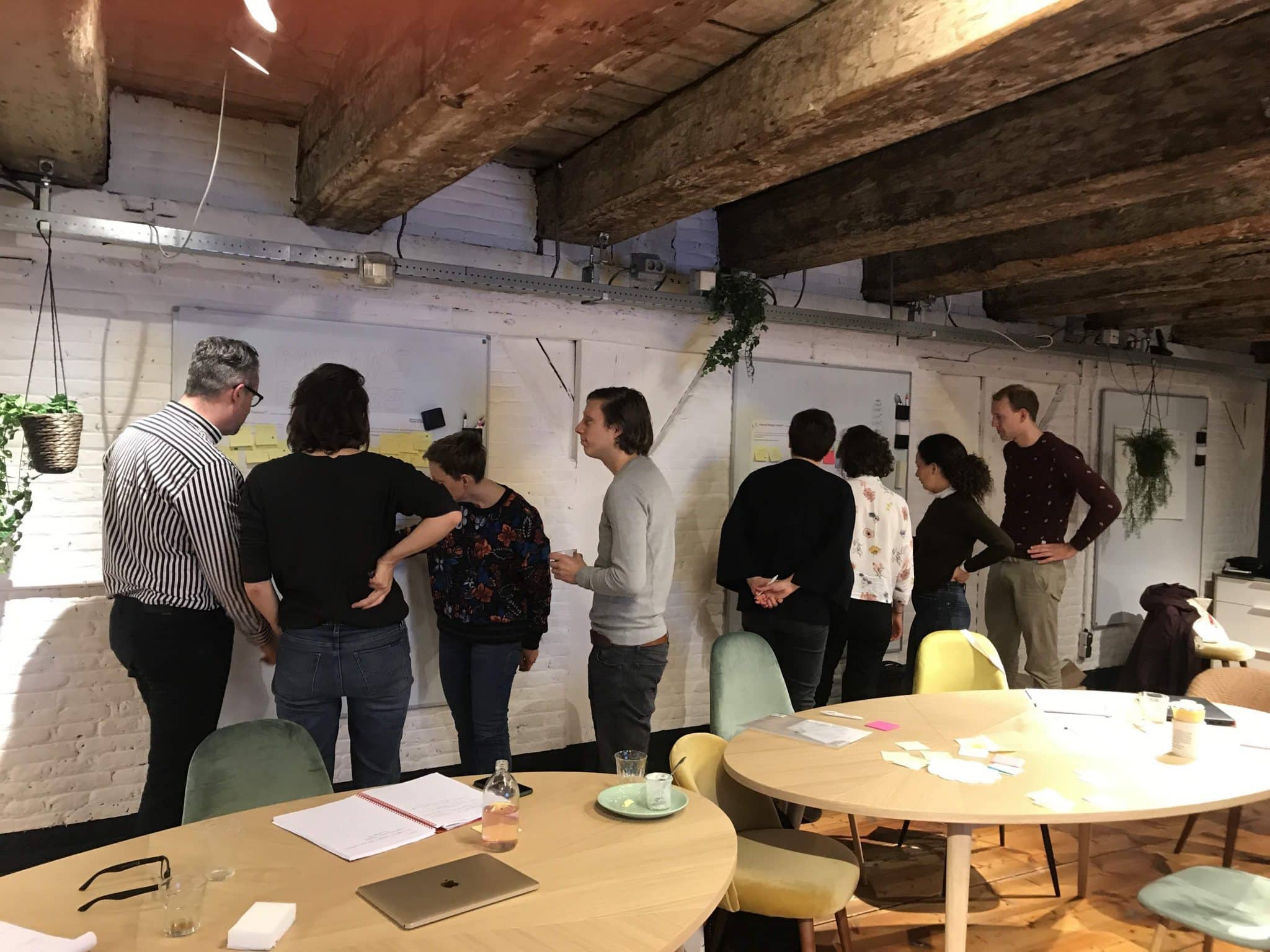

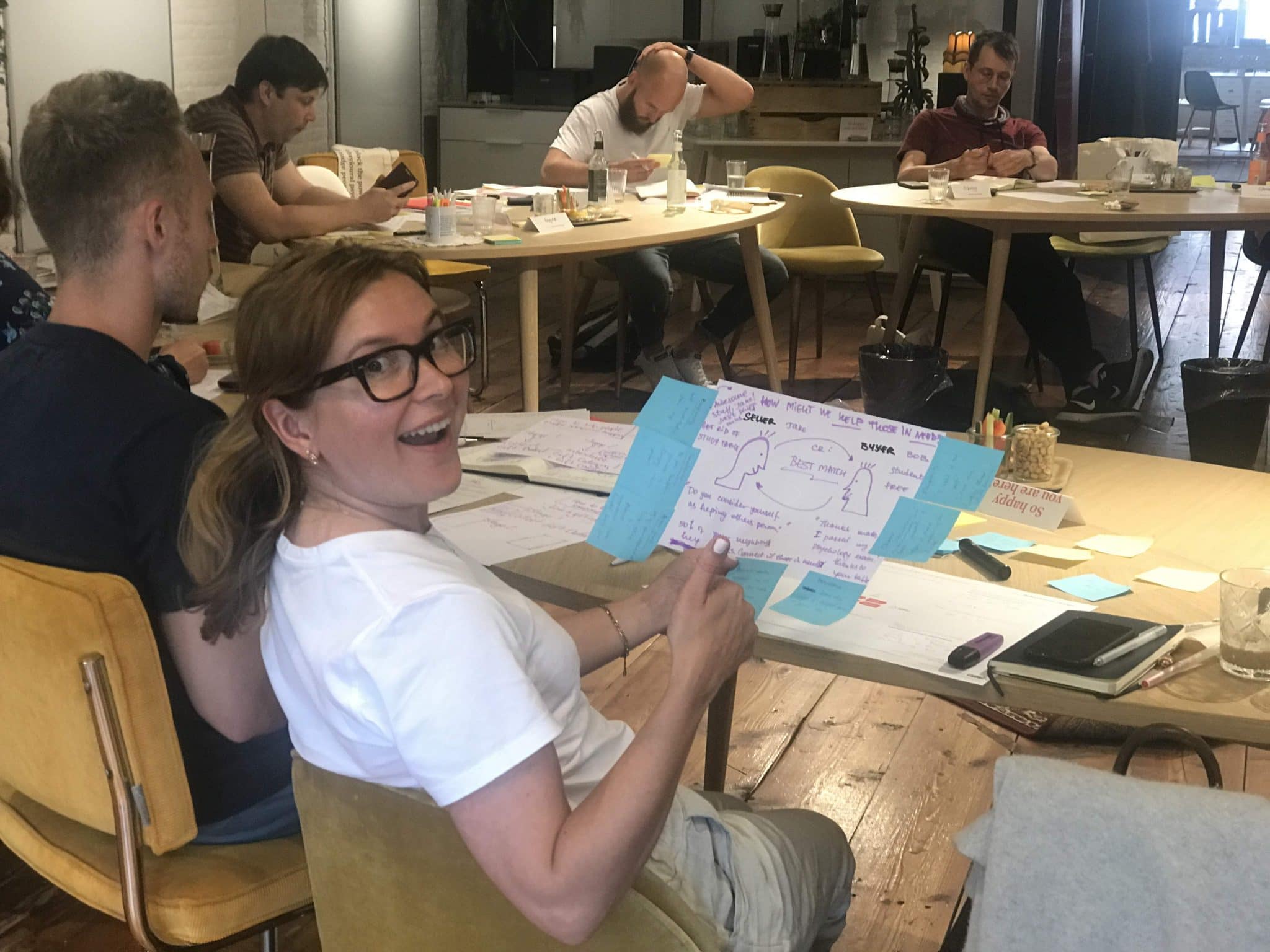

Suppose you want to learn more about how influence works. In that case, you might want to consider joining our Behavioural Design Academy, our officially accredited educational institution that already trained 2500+ people from 45+ countries in applied Behavioural Design. Or book an in-company training or one-day workshop for your team. In our top-notch training, we teach the Behavioural Design Method© and the Influence Framework©. Two powerful tools to make behavioural change happen in practice.

You can also hire SUE to help you to bring an innovative perspective on your product, service, policy or marketing. In a Behavioural Design Sprint, we help you shape choice and desired behaviours using a mix of behavioural psychology and creativity.

You can download the Behavioural Design Fundamentals Course brochure, contact us here or subscribe to our Behavioural Design Digest. This is our weekly newsletter in which we deconstruct how influence works in work, life and society.

Or maybe, you’re just curious about SUE | Behavioural Design. Here’s where you can read our backstory.

Mental accounting: How humans violate the economic theory

Mental accounting: How humans violate the economic theory

Mental accounting: The sunk cost effect

Mental accounting: The sunk cost effect Mental accounting: Using it for better decision-making

Mental accounting: Using it for better decision-making Suppose you want to learn more about how influence works. In that case, you might want to consider joining our

Suppose you want to learn more about how influence works. In that case, you might want to consider joining our

There is a cognitive bias related to this phenomenon called

There is a cognitive bias related to this phenomenon called

How to convince someone with different beliefs

How to convince someone with different beliefs

Bypassing confirmation bias (2): Provide proof not evidence

Bypassing confirmation bias (2): Provide proof not evidence