I have spent a lot of time reading lately about identity, and its role in politics as well as in human decision-making. Isn’t it bizarre that the challenges of the COVID-19 crisis and the emerging climate crisis should urge us to overcome our differences and start collaborating on an unprecedented scale? Yet, all we are capable of is quarrelling about who we are? We need to examen the hidden role of identity in behavioural change. And I believe that overcoming our obsession with our identity is probably one of the biggest challenges of today if we want humanity to deal with the mega-challenges it’s facing.

Both the left and the right are sharing the same obsession.

Both the left and the right are sharing the same obsession.

‘Don’t think of an elephant’. Never was a book title as revealing as George Lakoff’s famous book on political framing. With this provocative title, he illustrated the point that fighting a frame strengthens it. In other words: If I ask you not to think of an elephant, you cannot help but think about elephants. If I try to argue that immigration is not the problem, I reinforce the frame that the real discussion is indeed about immigration.

Identity has become the dominant frame in public discourse. All over the world, right-wing national populists are trying to win elections with a romantic idea of what it means to be a Real Dutch, A real Hungarian, a real American, etc. In their world view, the pure soul of a nation is being compromised by uncontrolled immigration, liberal politics, Muslims, gays, radical-left postmodernist academics and [fill in the blanks]. What they’re selling is a return to a ‘pastopia’, an idealised version of the past.

Meanwhile, the left has gradually fallen back into a similar toxic obsession with identity. All the anger and resentment around cancel culture (see picture below), Black Pete, transgender rights, and wokeness, are all about a deep craving for respect for this particular part of their identity.

Whereas the radical right is craving for a monolithic group identity around conservative Christian values, are the left craving for recognition of their niche identities. It’s pretty much the same story, only a different flavour.

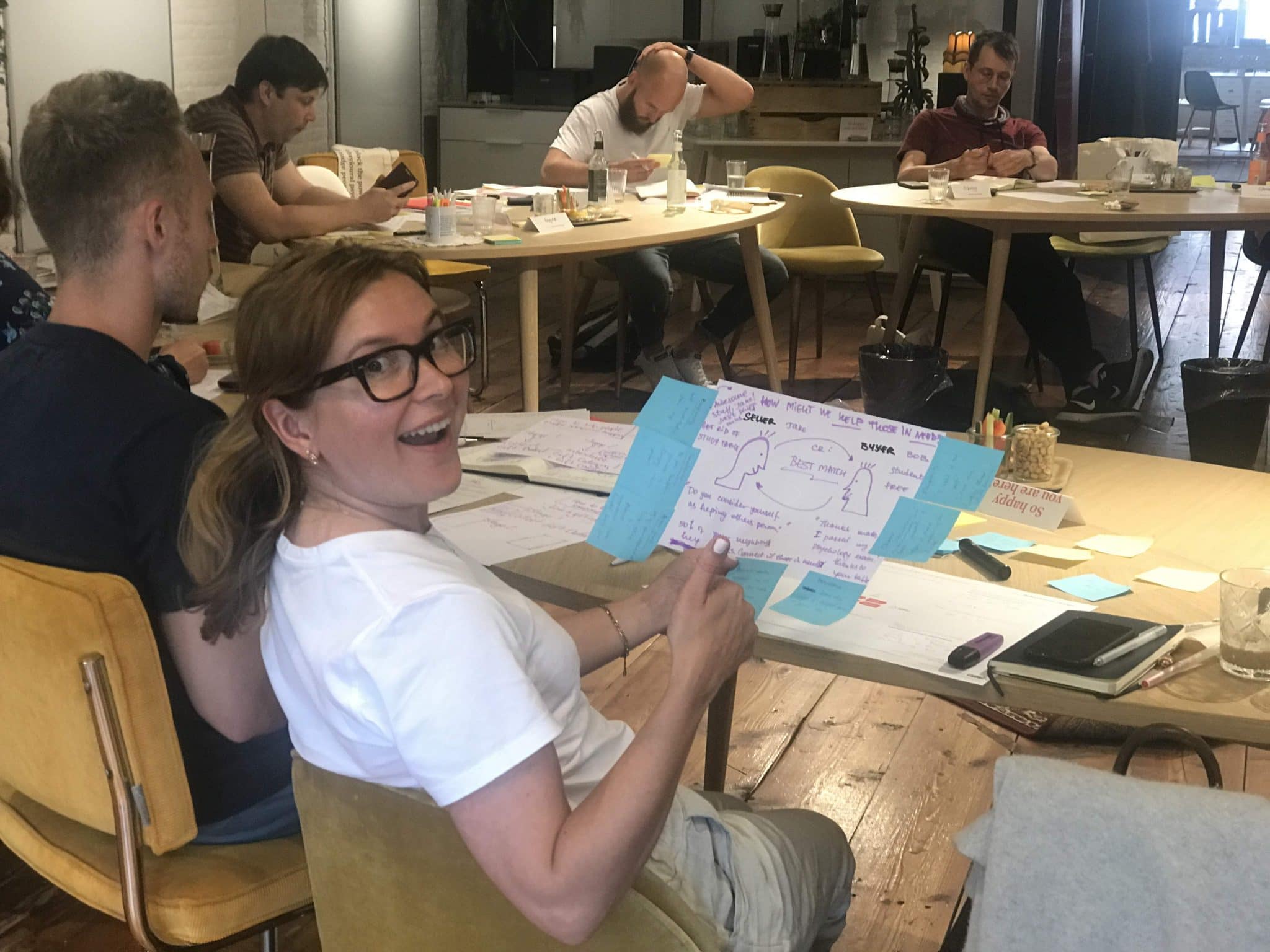

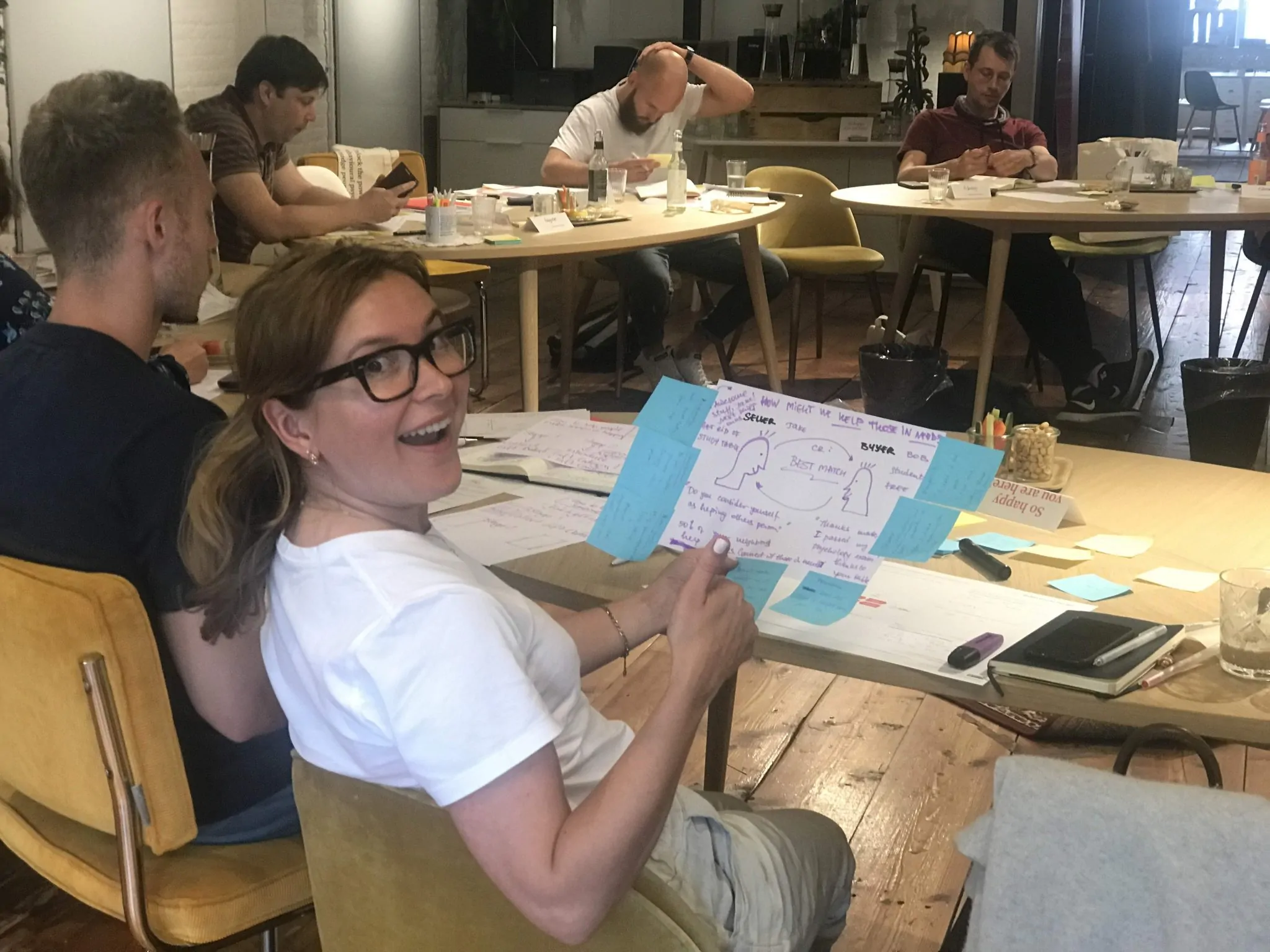

Would you like to leverage behavioural science to crack your thorny strategic challenges?

You can do this in our fast-paced and evidence-based Behavioural Design Sprint. We have created a brochure telling you all about the details of this approach. Such as the added value, the deliverables, the set up, and more. Should you have any further questions, please feel free to contact us. We are happy to help!

Where does this obsession come from?

The Dutch philosopher Bas Heijne, recently published a beautiful essay on identity and liberalism, called “mens/nonmens”, roughly translated as “human/inhuman”. In this essay, he asks himself the question of why liberalism has such much difficulty to deal with ‘nationalpopulism’. I found his answer quite surprising. The problem with liberalism (and moderate politics in general) is that they stopped having a seductive vision about the future. They act as if the current society is the pinnacle of human achievement, and that our only task is to manage it properly. But more and more people understand perfectly well that the deal that their parents had with society isn’t working for them anymore. The essence of this deal was that if you work hard, you will be able to have a house, your kids can get a proper education, and when you finish your career, there’s going to be a nice pension waiting for you to enjoy the last part of your life.

Historian Philip Blom argues that for more and more people, this contract with society is broken. No matter how hard you work today, you can’t make ends meet, while the rich are getting richer. Buying a house means entering a world of lifelong debt, just like trying to get a proper education. It seems that the wealthy have re-written the rules to benefit their interest.

The reason why ‘nationalpopulists’ have such an appeal, even when they are flawed or openly corrupt individuals themselves, is that they do a far better job in harvesting these feelings of anger for being left behind. They offer something precious in return: a utopia from the past, where society was structured amongst clear lines, where life was simple, where you derived part of your pride from your place in that society, and where virtues and values still mean something. Populists like Putin and Orban are romantic nostalgia. They reject – in the words of Philip Blom – a technocratic world that has been stripped away from all of its magic.

The liberal world that people reject is the cold and hypercompetitive world that consists of individual consumers. A world that keeps reminding you that no matter how much you buy to express your deeper needs and desires, there’s always a group of better people than you: more prosperous, more successful,… No matter what you do, you will still feel insecure and failed.

Bas Heijne observes that identity only comes into play when it’s under threat. When your world is neatly structured, and your future is bright, you don’t need to think about identity. Only when your identity is under threat, you will start shopping for new answers.

Both the radical left and radical right are more than happy to supply answers to this ‘market demand’ for identity.

Why this is problematic, and what to do about it?

Already in the 1930s, the English psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion observed in his famous book “Experiences in Groups” that groups can only overcome their unconscious tendencies for fighting, flighting, and their dependencies on leaders, by forming what he calls “working groups”. If a group succeeds in joining forces to solve a problem, they will be able to overcome the irrational and destructive forces that the group will revert to by default. Put us in groups, and we still are hardwired to act like a band of primates.

This vision about what kind of society we would like to become is the key element that is missing in politics. We need a story about the sort of community we want to create, not in terms of wealth, but also in terms of the quality of life. Wealth – although important, when there’s not enough of it – turns out to be an empty dream. The market has a big appetite for ideas and stories about how we could design a society in which you can live a qualitative life in a qualitative ecosystem.

More and more thinkers come to the same conclusion. Leading economist Mariana Mazzucato argues in her book “the value of everything” that societies need big hairy audacious projects to bundle excitement, energy, capital and innovation towards solving a wicked problem like eradicating poverty or achieving a CO2-neutral economy.

Does this mean we have to get rid of identity politics? Not at all. We need even more of it. People crave more than ever for a sense of identity, belonging and meaning. Liberals or moderates need to start telling a compelling story about how ‘a society worth living in’ should look like and how we’re going to get there by joining forces and becoming a working group. If not, they will leave the market for identity to nostalgics, frustrated Millenials and radicals.

This is what’s at stake.

BONUS: free ebook 'How to Convince Someone who Believes the Exact Opposite?'

Especially for you we've created a free eBook 'How to Convince Someone who Believes the Exact Opposite?'. For you to keep at hand, so you can start using the insights from this blog post whenever you want—it is a little gift from us to you.

How do you do. Our name is SUE.

Do you want to learn more?

Suppose you want to learn more about how influence works. In that case, you might want to consider joining our Behavioural Design Academy, our officially accredited educational institution that already trained 2500+ people from 45+ countries in applied Behavioural Design. Or book an in-company training or one-day workshop for your team. In our top-notch training, we teach the Behavioural Design Method© and the Influence Framework©. Two powerful tools to make behavioural change happen in practice.

You can also hire SUE to help you to bring an innovative perspective on your product, service, policy or marketing. In a Behavioural Design Sprint, we help you shape choice and desired behaviours using a mix of behavioural psychology and creativity.

You can download the Behavioural Design Fundamentals Course brochure, contact us here or subscribe to our Behavioural Design Digest. This is our weekly newsletter in which we deconstruct how influence works in work, life and society.

Or maybe, you’re just curious about SUE | Behavioural Design. Here’s where you can read our backstory.

These are just two classic examples of the concept of “pissing in the well”. A well is a common good in a community that – if managed well – provides prosperity for everyone. If a community in a remote village manages its access to water well, everyone will be able to thrive. If one person decides to damage it for personal gain, the well will dry up and everyone will suffer or die. This phenomenon is also often referred to as the tragedy of the commons.

These are just two classic examples of the concept of “pissing in the well”. A well is a common good in a community that – if managed well – provides prosperity for everyone. If a community in a remote village manages its access to water well, everyone will be able to thrive. If one person decides to damage it for personal gain, the well will dry up and everyone will suffer or die. This phenomenon is also often referred to as the tragedy of the commons.