Five teams of Behavioural Design Academy alumni spend an afternoon trying to change behaviour to make the world a better place. That is the SUE Hackathon. The challenge for the first edition came from the City of Rotterdam: Get Rotterdammers to replace garden tiles with pieces of greenery.

The issue

The question of the City of Rotterdam sounds simple but turns out to be very difficult. There are a lot of human peculiarities involved in the design of a garden. Everyone’s garden is different. What is common is that gardens are seen as an essential addition to the interior of your home. It has to be beautiful for most people, but above all, it has to be easy on the eye. When it comes to the greenery in the garden, people often think: the more green, the more hassle. And that isn’t good for the quality of life and biodiversity.

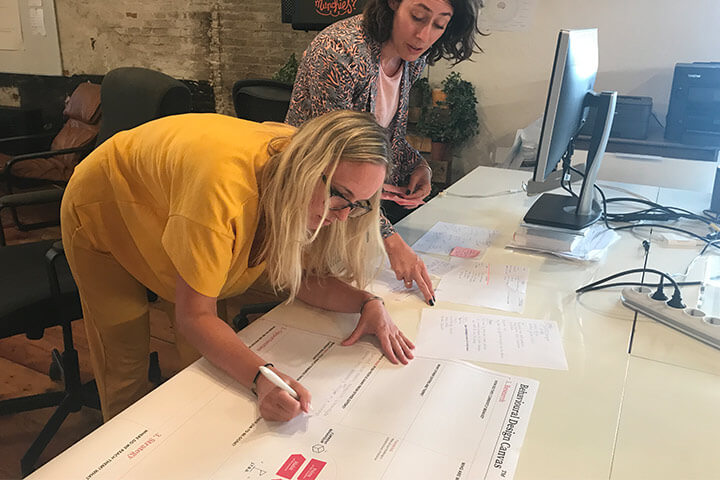

How did we proceed?

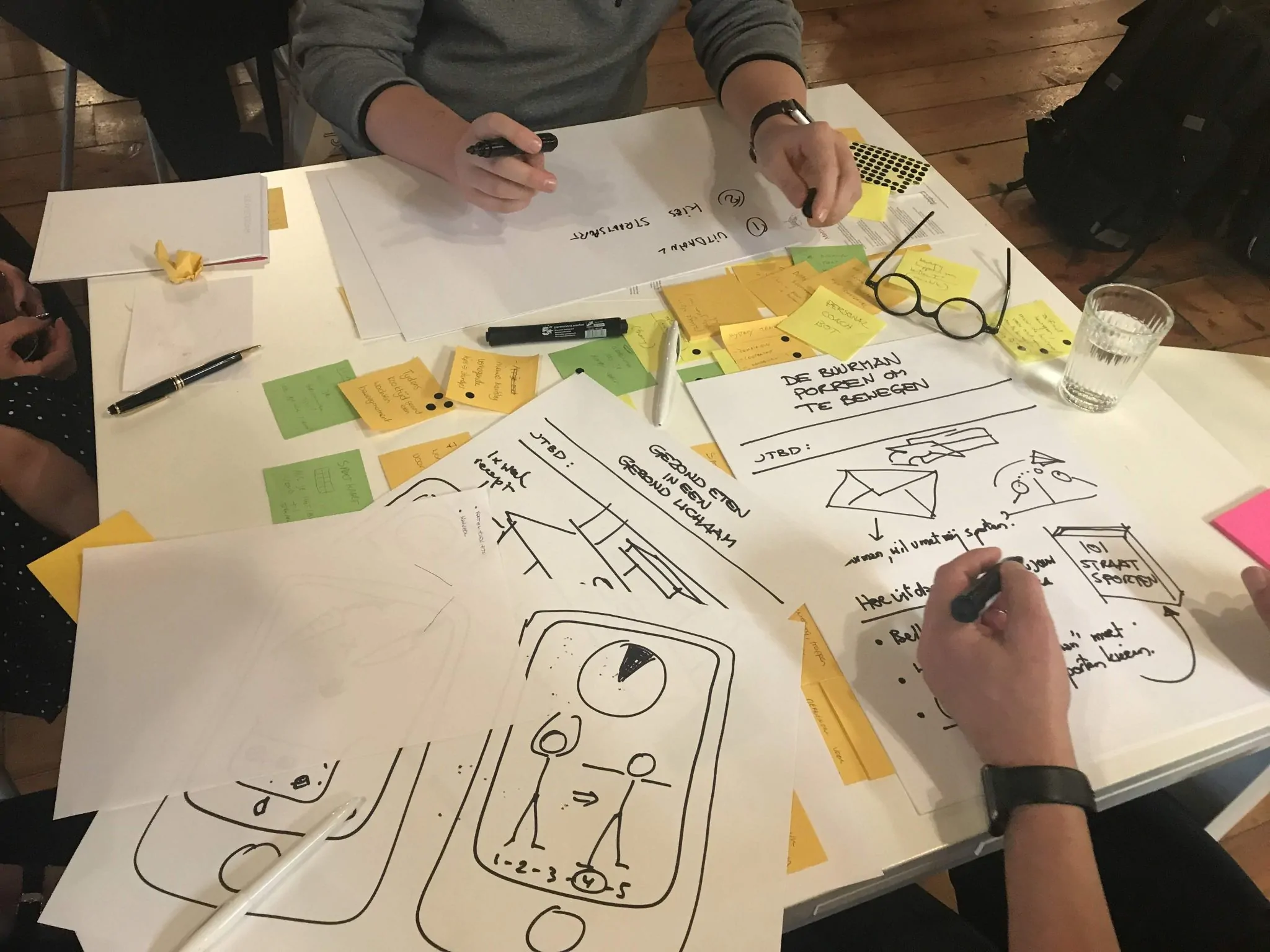

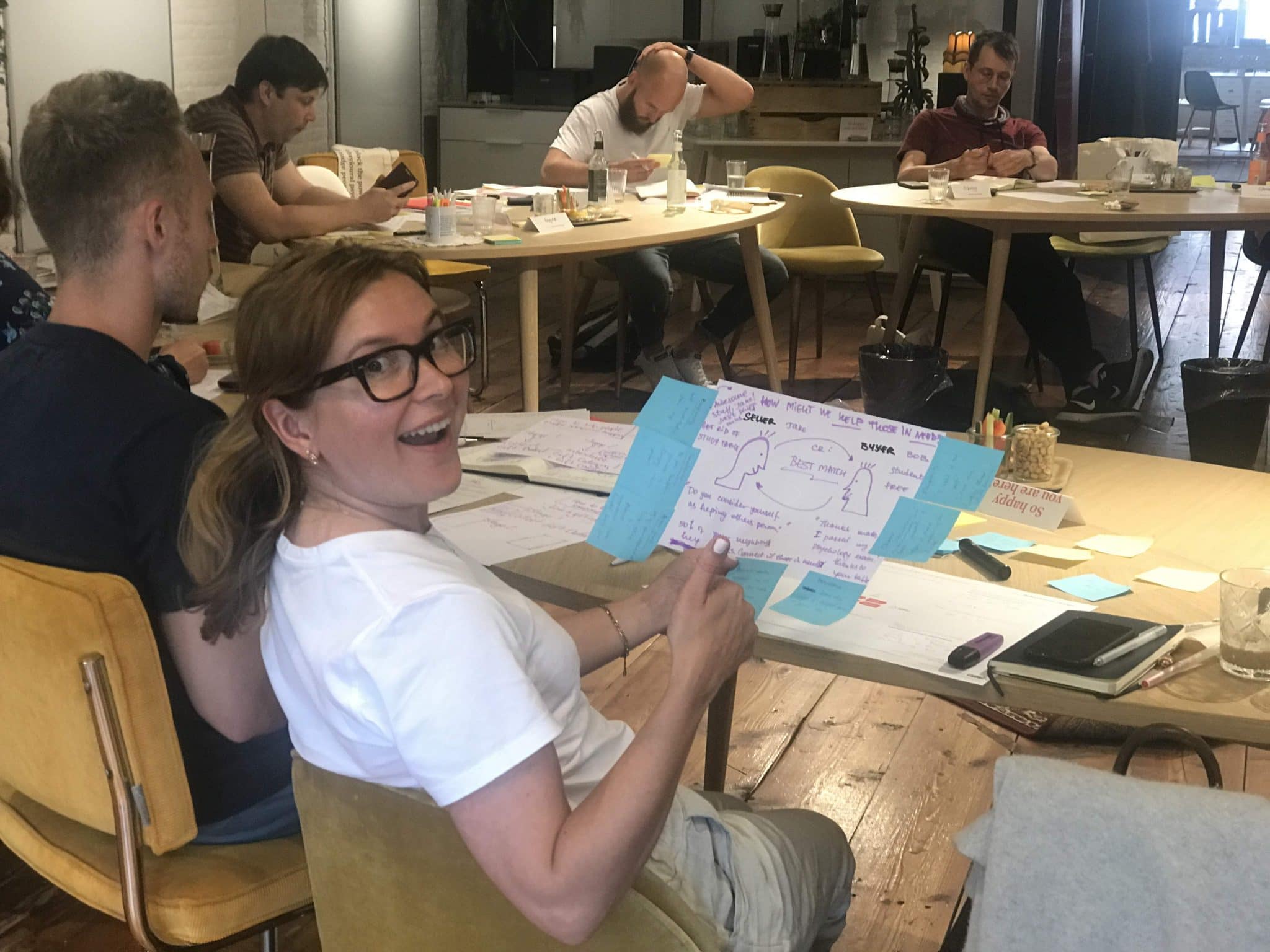

The teams received a kick-off from Vincent Karremans, alderman of the City of Rotterdam. During the kick-off, the City of Rotterdam shared the insights they had already gained in the past. The teams were extremely enthusiastic. With the insights from the kick-off, the teams could get to work. They pulled out all the stops by carrying out a rapid behavioural analysis on their own initiative. They phoned various people who have a garden to ask them about their motivations for garden design.

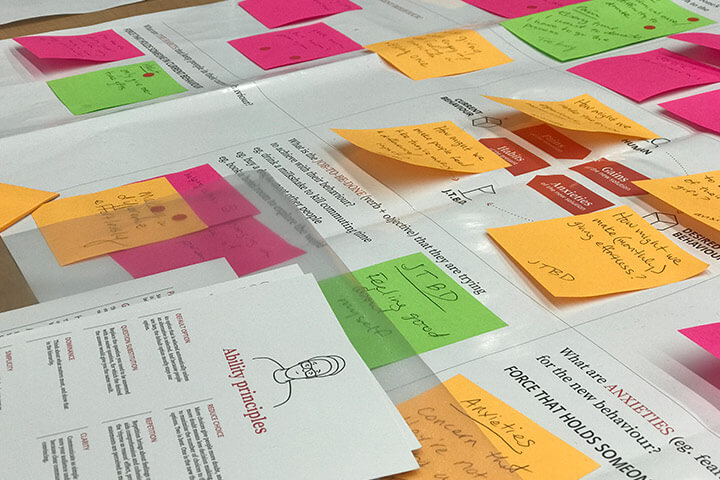

Insights

A great deal of resistance was discovered. For example, there is a lack of knowledge about maintaining greenery and what kind of greenery can replace tiles. People are also afraid that it will result in dirty shoes. And if people have to choose, they would rather have a slightly more boring garden with tiles than a poorly maintained green garden. Many teams came to the sobering realisation that tremendous help is needed for a large-scale change. Tossing a few tiles seems easy, but the deeper you delve into the issue, the more complex the solutions prove to be. For Alderman Karremans, was this a clear realisation as well: on a large scale, a lot of money, time and effort will have to be put into this issue.

Get more detailed information.

Download our Behavioural design Sprint brochure telling you all about the ins and outs of the sprint in detail. Please feel free to contact us suppose you would like some more information. We gladly tell you all about the possibilities.

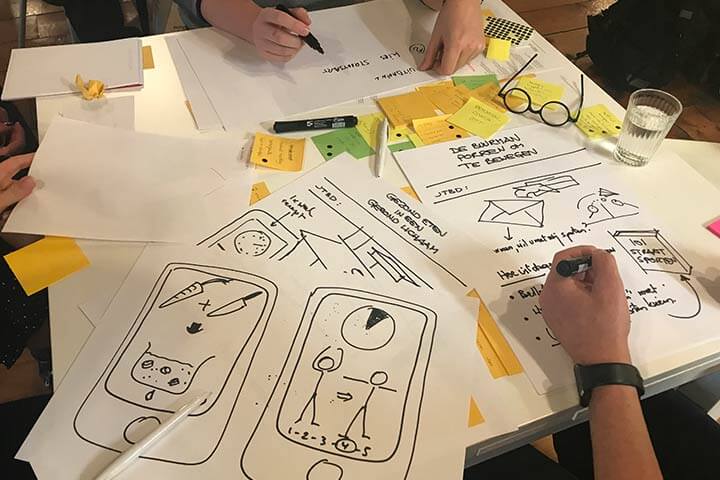

Great ideas

In six hours, the teams managed to present interesting ideas at various levels. One of the ideas was to stimulate façade gardens by indicating with lines where façade gardens are allowed. And… the houses with visible lines do not yet contribute to a greener climate – a good form of social pressure. Interesting ideas also emerged for market parties, such as designing pieces of greenery in the dimensions of garden tiles. In that way, you can easily remove your tile and replace it with something green. Or adapt your garden to who you are, such as incorporating a typical cultural symbol in your garden. The winning team came up with a very original idea, with which you can place what you like to identify within your garden. What this is exactly, remains a surprise. The City of Rotterdam is in the process of actually implementing this idea. So keep a close eye on the news from the City of Rotterdam.

Yes, it works!

The participants had fun, but they also sweated. At one point, we even heard the team that had emerged as the winner say: “Are we even going to make it?” The lesson? Behavioural Design is never easy, but something special always comes out of it if you follow the steps carefully. The stress balls, stress-control deodorant and energy bars also helped, of course!

Challenge yourself in Behavioural Design

Would you like to challenge yourself more in Behavioural Design? Then take a look at the Behavioural Design Academy. Here you will learn the basics of Behavioural Design within two days so that next time you will be able to participate in the Hackathon.

Have you already followed the Behavioural Design Academy, and are you ready for a further step? In the Advanced Course, we will train you to become an accredited Behavioural Designer. You learn from A to Z how to set up and lead a Behavioural Design project while working on your own case. This enables you to work as a Behavioural Designer in your own organisation on complex issues concerning behavioural change. Reserve your spot here.

In conclusion

We could not be happier with the results of our first Hackathon. We will repeat this event every year to give our alumni’s the chance to keep their knowledge up-to-date and work on a solution to a real-life problem!

Vice mayor Vincent Karremans was also very impressed by the results the candidates made in such a short time.

“Although many of the ideas need further work in order to be successfully guided through the decision-making process of the city government, the breadth and cleverness of the yield of these mere five hours were fantastic.”

See you next year!

Impression of the Hackathon

How do you do. Our name is SUE.

Do you want to learn more?

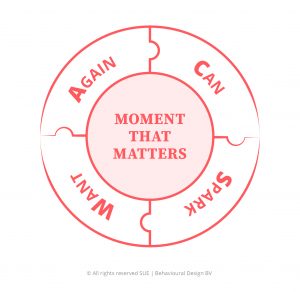

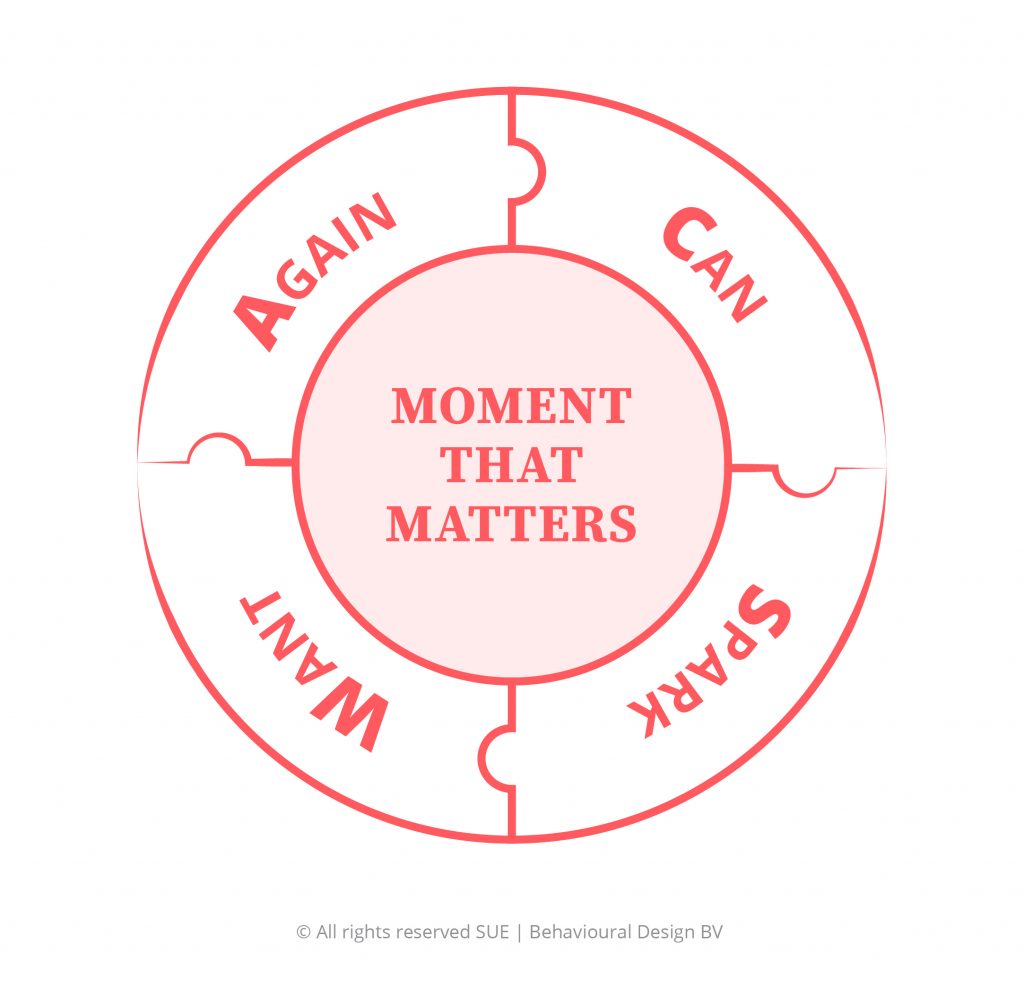

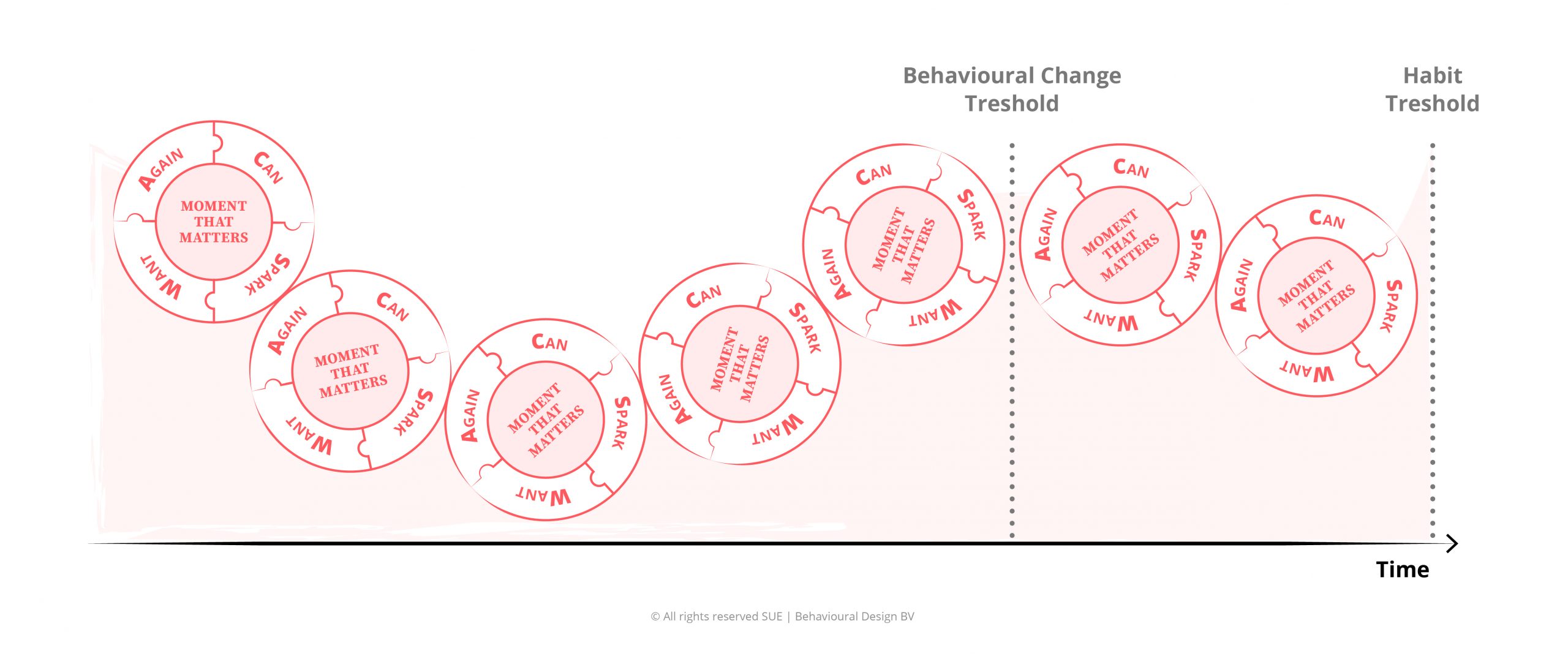

Suppose you want to learn more about how influence works. In that case, you might want to consider joining our Behavioural Design Academy, our officially accredited educational institution that already trained 2500+ people from 45+ countries in applied Behavioural Design. Or book an in-company training or one-day workshop for your team. In our top-notch training, we teach the Behavioural Design Method© and the Influence Framework©. Two powerful tools to make behavioural change happen in practice.

You can also hire SUE to help you to bring an innovative perspective on your product, service, policy or marketing. In a Behavioural Design Sprint, we help you shape choice and desired behaviours using a mix of behavioural psychology and creativity.

You can download the Behavioural Design Fundamentals Course brochure, contact us here or subscribe to our Behavioural Design Digest. This is our weekly newsletter in which we deconstruct how influence works in work, life and society.

Or maybe, you’re just curious about SUE | Behavioural Design. Here’s where you can read our backstory.

2. Meso-Forces: What are the needs I can tap into?

2. Meso-Forces: What are the needs I can tap into?

Mental accounting: How humans violate the economic theory

Mental accounting: How humans violate the economic theory

Mental accounting: The sunk cost effect

Mental accounting: The sunk cost effect Mental accounting: Using it for better decision-making

Mental accounting: Using it for better decision-making Suppose you want to learn more about how influence works. In that case, you might want to consider joining our

Suppose you want to learn more about how influence works. In that case, you might want to consider joining our

There is a cognitive bias related to this phenomenon called

There is a cognitive bias related to this phenomenon called

How to convince someone with different beliefs

How to convince someone with different beliefs

Bypassing confirmation bias (2): Provide proof not evidence

Bypassing confirmation bias (2): Provide proof not evidence