How to design behaviour: SWAC

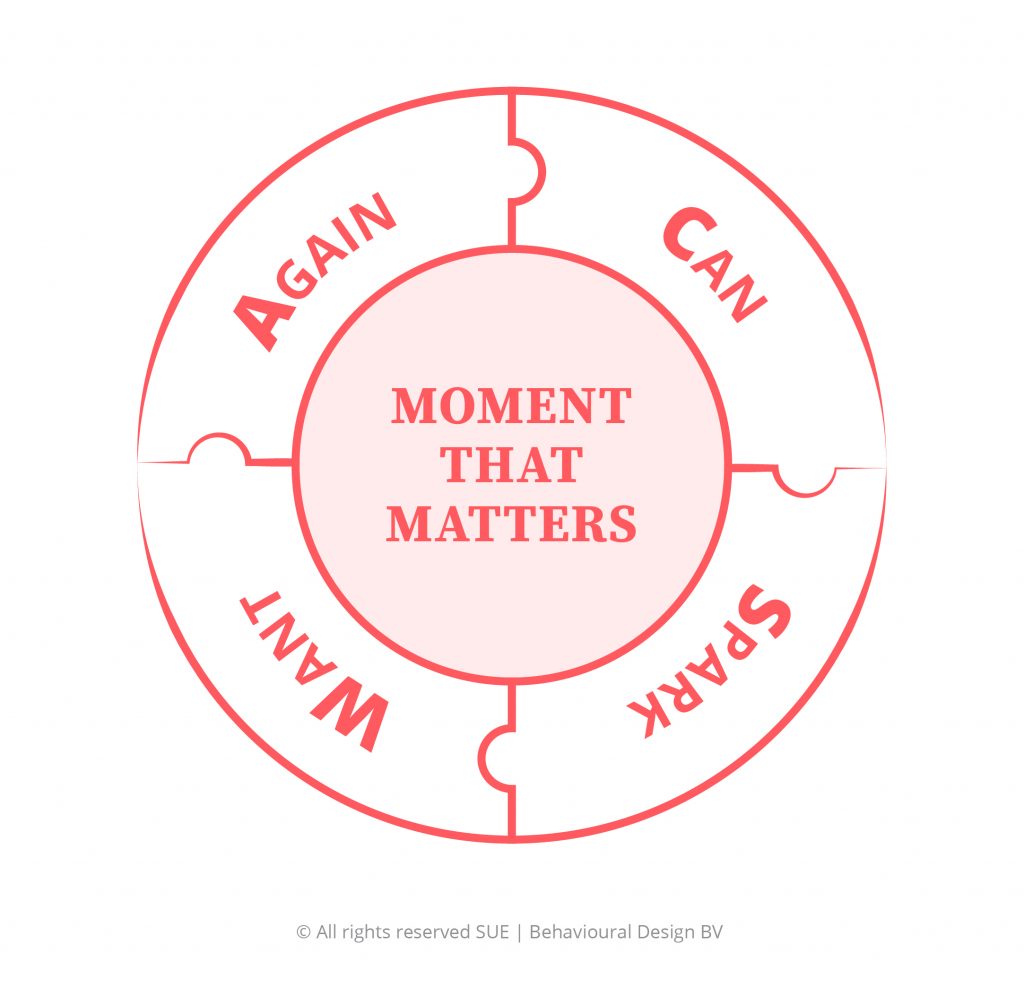

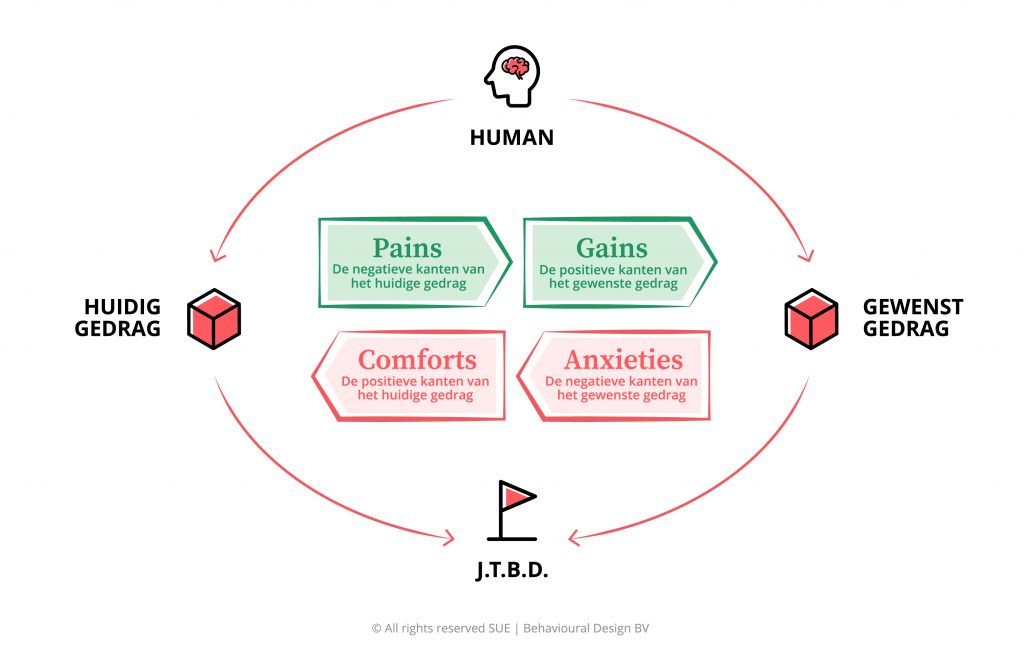

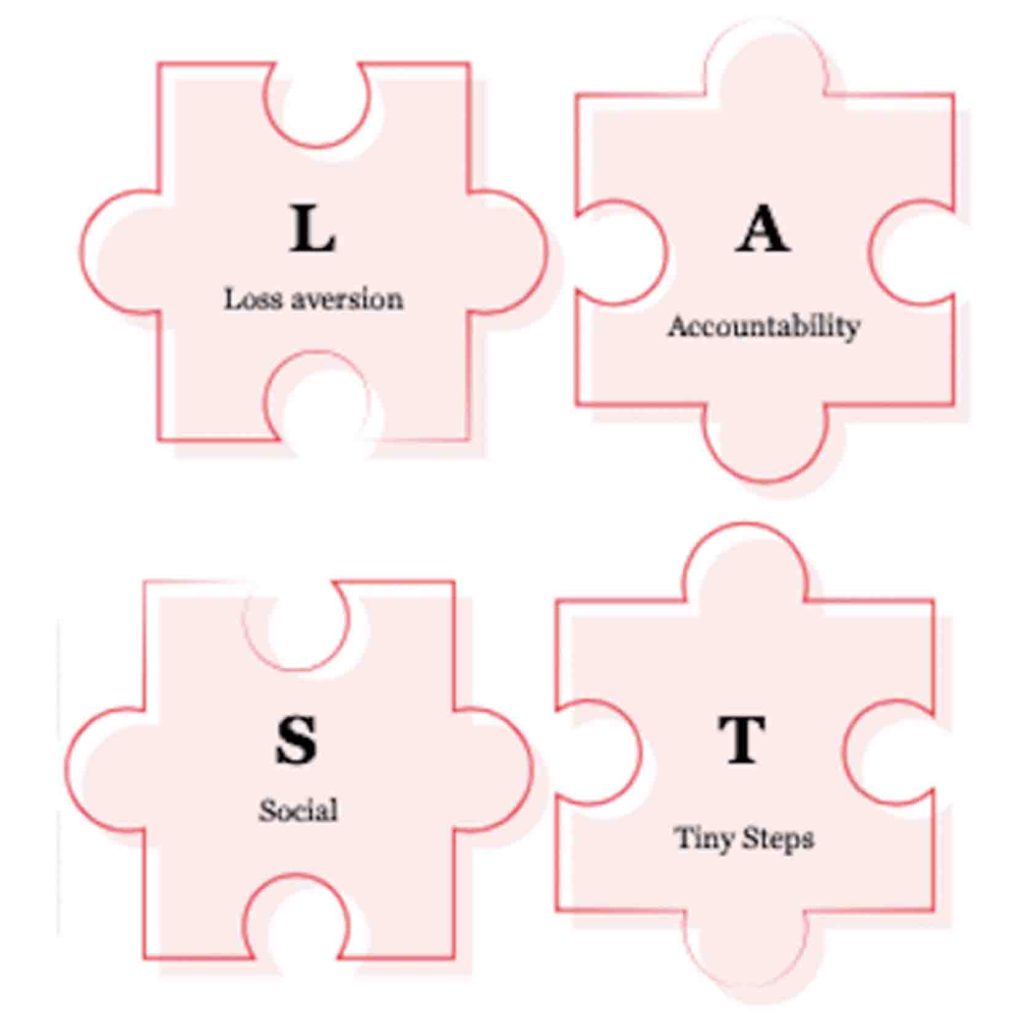

A lot of very interesting research has been done in the behavioural change field of expertise. And it can get quite complicated. That’s why we simplified it again. Without further ado let’s take a look at the SUE | SWAC Tool©. It is foremost a very easy-to-use tool. It explains which four pieces of the puzzle you need to solve to create a context that will persuade someone into doing something and to have them keep doing it. What makes the tool so easy to use in practice, is that anytime you want to design for behavioural change, all you have to do is ask yourself four simple questions:

When the new behaviour does not happen, at least one of those four elements is missing. The most important implication of this is that by using the SUE | SWAC Tool© as a guide you can quickly identify what stops people from performing the behaviours that you seek.

If a sufficient degree of capability (CAN) to perform a behaviour is matched with the willingness (WANT) to engage in that behaviour, all that is then needed for the behaviour to occur is to set someone into action (SPARK) at the Moments that Matter.

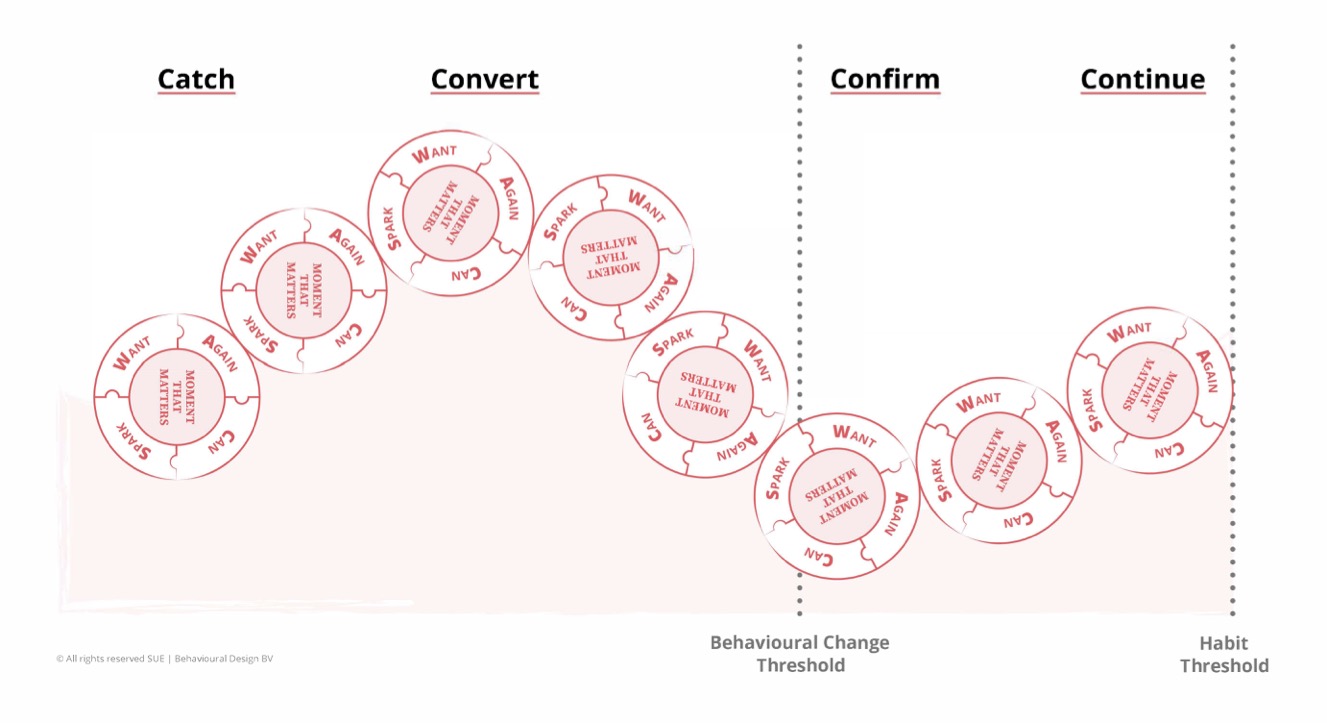

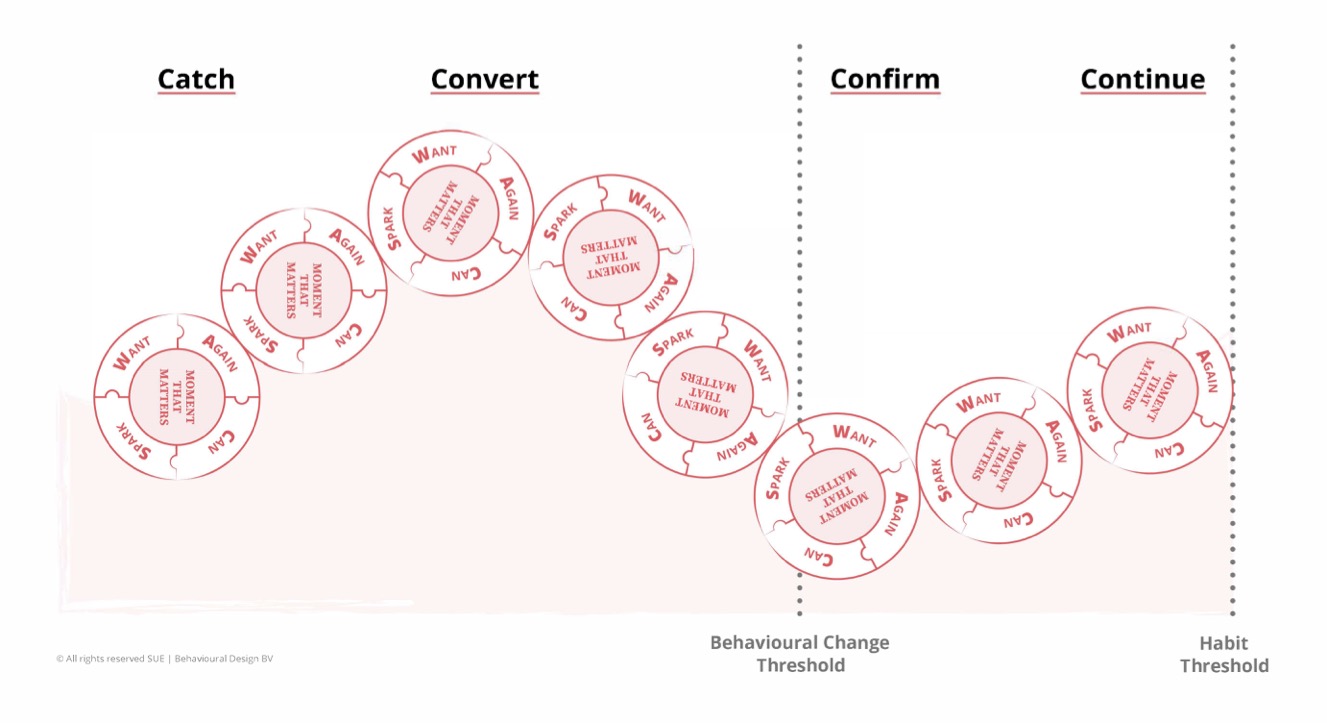

Maybe you notice that in the tool it says moments that matter. Not one moment, but moments. As we learned, behavioural change doesn’t happen overnight. Most of the time someone needs to be reminded of the desired behaviour more than once for it to happen in the first place. Furthermore, behaviour becomes easier when repeated. Therefore, we have to make sure we SPARK someone AGAIN and again to activate the desired behaviour. So, you need to design several interventions at multiple moments that matter. In practice your intervention strategy will look something like this:

The objective of most intervention strategies is not only to change behaviour but to change this new behaviour into a routine behaviour (a habit), so the new behaviour will stick.

Remember, your desired behaviour is new behaviour for people and that’s why it is important to spark behaviour AGAIN and again. Only then the behaviour will take place, as illustrated above as the BEHAVIOURAL CHANGE THRESHOLD. When your objective is to design repeat behaviour, it almost goes without saying that you have to make sure the desired behaviour is performed repeatedly. If you can make someone perform new behaviour over and over AGAIN, it can become automatic.

The result being that someone doesn’t have to think about the new behaviour anymore, he or she simply does it. This way it can become habitual. Illustrated above model as the HABIT THRESHOLD. As Aristotle already stated:

We are what we repeatedly do.

He added ‘Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit’. To sum it up: The more often you do something, the easier it gets. So, there you have it: the four elements you need to change behaviour.

Aristotle quote, ancient Greek philosopher, scientist and physician, 384 BC-322 BC, no original source known.

How to design behaviour: Capability

Before we start working with the tool, let’s go back one little bit. As Behavioural Designers our outset is to design for someone’s system 1.

Our job is to help people make better decisions without them having to think.

This is the foundation of this model. When you look at willingness (WANT) and capability (CAN) there is something very interesting and important going on. We are all so used (and trained) to have the best arguments, deals, offers, rewards or promises to convince someone (or ourselves). Historically, we are all shaped around motivation (WANT). If we need to sell something, we are hardwired to try to create willingness to buy. If a personal resolution fails, our first (conditioned) conclusion is that we must not have wanted it badly enough to keep up the self-discipline.

What if I tell you that making sure someone wants something often isn’t the most powerful starting point to change behaviour? Making someone WANTs to perform the desired behaviour is just one side of the medal in getting things done. In fact, it even isn’t the shiniest side of the medal. Here’s why. There is something particular going on with people’s willingness to change; It goes up and down. When relating this to our fundamental know-how on human decision-making this makes perfect sense, as:

Willingness to change requires cognitive action.

It is a system 2 activity like self-control and focus. You cognitively decide you want something. You decide this consciously. I want to lose weight, I want to save money, I want to recycle, I want to spend more time with my kids. We have learned that our system 2 has only limited bandwidth. Therefore, your willingness to change falters, it goes up and down in waves. This is the reason why most new year’s resolutions fail. On January 1st you WANT to lose weight, or you WANT to stop drinking or you WANT to go to the gym. And then comes along your best friend’s birthday. Or you’ve pulled a whole-nighter because that precious offspring of yours refused to sleep. And now you don’t WANT to exercise and not drink anymore. You want to vegetate on the couch (sleep deprivation isn’t a walk in the park) or have a blast (hey your friend only turns 40 once). You feel so deserving (your system 2 post-rationalisation working full speed for you) and so you will start next month. You simply CANnot do it today. Your willingness to change behaviour has dropped like a mic on an empty stage. This is perfectly human, but something we have to take into account when designing for behaviour change. Chaos Monkey Galore!

Luckily, as Behavioural Designer, you have an ace up your sleeve by making behaviour very simple. Our brain LOVES simple. Bonus is that when things are simple, we are able to do things without needing that much willingness. That’s why we always start with thinking about possible CAN interventions. This is designing for system 1. The best behavioural change ideas are in their core capability ideas.

Making something very easy to do is something that requires little or no cognitive action from someone.

Let me illustrate how this can work with a real-life example. Most people WANT to save money, but many of find it hard to do (CAN). You could design saving behaviour without having to really stress the willingness to save too much but by focusing on making saving behaviour easier instead. This is exactly what Bank of America did. Their human insight was that people wanted to save money, but never did especially making regular contributions was very hard. They have introduced a program called ‘Keep the Change’. What it boils down to is that every time a client pays with his or her debit card for daily purchases like buying coffee, going to the dry cleaners and so on, they round up their purchase to the nearest dollar amount and transfer the change from someone’s checking account to their savings account — or to their child’s savings account.

From a JTBD point of view, I find the last brilliant by the way: a lot of parents want to save money to for their children to have a little money in the bank once they go to college or need some extra funds otherwise. So, let’s say you have to pay something of $ 4,60 then $ 0,40 is automatically transferred. You don’t have to think about it, it just has been made very simple for you. The result of this behavioural design intervention has been very impactful. Ever since the program launched in September of 2005, more than 12.3 million customers have enrolled, saving a total of more than 2 billion dollars. Of all new customers, 60% enrol in the program and Bank of America reported that 99% of the people who signed-up with the program have stayed with it.

The situation: we’re in the middle of The Big Quit

The situation: we’re in the middle of The Big Quit

4. Expert biases, groupthink and cherry-picking the insights that match our beliefs

4. Expert biases, groupthink and cherry-picking the insights that match our beliefs